Having looked at a variety of beginner training programs in Part 4, I want to wrap up this series by looking at a grab back of different topics including warming up, cardio and stretching and when and how to progress or introduce variety into training.

Table of Contents

Warming-Up

I’ve written extensively about warming up on the website but want to look at the topic briefly here as it pertains to beginners. It’s generally recommended that some type of general warm-up such as low intensity cardio be done prior to weight training. The goal here is to generally warm up the tissues of the body in preparation for harder work.

At the same time, many who lift don’t bother with this at all and simply use their first exercise to warm-up for that exercise. My old mentor for example suffered from squat rank anxiety. When he’d get to the gym he’d run to the squat rack to claim it for fear of it getting taken.

I can’t recall the last time I did a general warm-up and my powerlifting trainee has never done one. However, I’ve been training for decades and she has too and we can both jump straight into our primary movements without doing anything else. That’s not necessarily the case for a total beginner.

That said, it can be useful for beginners. For those seeking general fitness and health, the general warm-up can begin to build some basic fitness. In fact, I’d often have beginner clients just get the cardio out of the way. Mainly this was to ensure that it got done.

For beginners with a very low exercise tolerance, doing a small amount of aerobic work before and after the weight training is a good way to start to accumulate time. So they might do 5 minutes before and after and get 10 total minutes. Then bump each up gradually to accumulate the full 20 minutes. I’ll talk more about cardio below.

For everybody else, well, a general aerobic warm-up might be useful for some and a waste of time for others. When it’s very cold where you’re training I do suggest doing a little. Older trainees who may be a little bit stiffer in their joints will probably find that a little low intensity aerobic work can help get things moving.

Stretching

And then there is the issue of stretching. First let me define some terms, the different types of stretching that can be done.

- Static stretching is the type most are familiar with. Here you put a muscle on stretch and just hold it for some amount of time until the tissue relaxes.

- Dynamic stretching is more active. Here the joints are taken through progressively increasing ranges of motion by dynamically. So someone might start swinging their leg side to side, gradually increasing the range of motion over 10 or so repetitions.

- Finally there is ballistic stretching where the body part is literally kind of thrown and then left to its own devices.

For literally decades stretching was recommended as part of the general warm-up for….reasons. It was thought to be necessary for optimal performance or helped improvement or what have you. It was often recommended to be done after training as well, often to reduce soreness. And as it turns out, none of these things are really true.

Actually it’s more nuanced than that. Both very low and very high levels of flexibility can be associated with injury and there is an optimal level. Some research shows that excessive static stretching before training hampers performance. Many recommend dynamic stretching pre-workout and static stretching after or later in the day.

But what about beginners? Well just like with cardio, stretching of some sort may or may not be needed. If it is required to perform an exercise properly, it should be done. For example, tight muscles can often prevent people from squatting without their low back rounding. Tight shoulders can cause problem benching. If some stretching or mobility work before training those movements helps, do it. Any small difference in performance or what have you is totally secondary to proper exercise performance in this case.

I would note that, by and large, women are far more flexible and more mobile than men. Until later in life, they are highly unlikely to need any sort of mobility work (even if they often want to do a lot of it). Rather, it’s relatively more inflexible men who need the remedial work here.

Mind you, many will recommend simply using the exercises themselves to increase flexibility and mobility. So in a squat, the trainee would attempt to gradually squat deeper and this will gradually stretch out the relevant tissues. There is much merit to this but specific stretching sessions before or after training may be warranted for especially tight muscles to allow for proper exercise performance.

But that brings me somewhat indirectly to:

Warm-Up Sets

As discussed in more detail in the article linked above, warm-up sets serve multiple purposes. One is to warm-up the body (literally) for optimal performance of heavier work. It also provides a time to get that much more proper technical practice. And this is true for both beginners and more advanced.

If you watch an advanced trainee you will always see them putting just as much focus into their warm-up sets as their work sets. Technique can never be too good or too automated. However, at higher levels much heavier weights are being lifted and these lifters need multiple warm-up sets to be prepared for their truly heavy work.

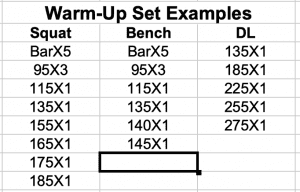

In practice, a lifter might do anywhere from 4-8 progressively heavier warm-up sets to reach their top weight, depending on how much they are lifting. Just for illustration, I’ve shown the actual warm-up my powerlifting trainee uses for her primary exercises.

So you can see that she does 8 low repetition warm-up sets for squats, 6 for bench and often only 5 for deadlift and this is before any of her actual working sets. This might seem odd given that her deadlift poundages are so much higher than her squat but she actually does both in the same workout and her squat training has already warmed her up so she doesn’t need as many sets. She’s also built to pull in a way she isn’t to squat and it takes her proportionally longer to get clicking on squats.

The point being that at higher levels, there may be a number of warm-up sets prior to the actual work sets to make sure that the lifter is prepared muscularly, neurologically and psychologically.

In contrast, in the very beginning stages of training, the sets of each exercise are so light to begin with that there is no functional difference between warm-up sets and work sets. In my beginner machine training routine, where a trainee is only doing 1 set, that’s all they need. Since it’s relatively light, they don’t need much of a warm-up set for several weeks.

At some point, when the single set starts to get heavier, I might have them do a single warm-up set at about 75% of the day’s goal weight as a warm-up. So if they were doing 12 plates on the leg press, I’d have them do 8 plates for 8 repetitions first then rest 30-60 seconds and do the heavier set.

They’d also only do warm-ups on the first exercise any set of muscles. After leg press, the hamstrings are warmed up for leg curls. After chest press and rows, they wouldn’t need additional warm-up sets for shoulder, lat or arm-work. Further down the road they might. In the early stages, they do not.

Even if a beginner pyramids his weights across 3 or 5 sets as in the 5X5 programs or basic barbell routine, even the top set won’t be that heavy until many weeks into training. By that point the initial sets are acting as still acting as warm-up sets anyhow.

So consider my mentor’s basic barbell routine or my modified version. If 3 sets of 10-12 in the squat are being done, the first two would be with lighter weights to practice technique, adding a little bit of weight so that the third set was a bit challenging. Even by the month or 6-week mark, the work weights are unlikely to be so heavy to need more than this. I’d note that the 5X5 programs work under the same approach, pyramiding up progressively to a single top set in the beginner programs.

But all of this really presumes that only one top heavy work set is being done. At some point, the lifter will want to increase this number although this may be many weeks down the road from when they start. At that point, they will still be performing the same initial warm-up sets but their total training volume may go up. In a basic barbell routine routine this might mean 2 progressive warmups to 2 or even 3 work sets at the same weight (usually called weight across).

In most 5X5 systems the next step “up” from beginner is warm-ups to 5 work sets of 5 with the same weight.

But all of that is at the intermediate stage anyhow. For the first 4-6 months of true beginner training, there shouldn’t be a huge need to do a lot of warm-up sets. One or two will usually be sufficient for quite some time. And as mentioned above, they should be used both to warm-up the tissue, achieve proper ranges of motion and practice proper technique.

Cardio

I’m not going to talk a lot about cardiovascular/aerobic exercise since the focus of this guide is on beginning weight training. However, I do want to mention it briefly. In general, I would say that most beginning trainees will probably benefit from some amount of cardio type exercise. For the general fitness and health trainee it is part of a well-rounded program to begin with.

But even in other cases, it can help improve overall fitness and tolerance to exercise which is part of the beginner build-up phase. For those seeking mass gains, cardio can often improve appetite. Some trainees (i.e. the so-called “hardgainer”) often have an appetite that shuts down rather easily. Getting them to eat enough consistently to gain muscle mass is often difficult and cardio may help here.

Even for someone eventually wanting to get into powerlifting, some amount of cardio may be useful. Again, this is just a general fitness and work tolerance thing. Many find that even small amounts of aerobic conditioning helps for recovery between sets.

This isn’t to say that excessive amounts much be done. A reasonable goal in the first few months of training might be a minimum of 20-30 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic exercise and perhaps a maximum of 45-60 minutes (and only there when fat loss is a primary goal). A nice thing about being a beginner is just how little exercise it takes to develop basic fitness.

Selecting Beginning Poundages

As I discussed in Part 3, beginners will gain the same strength gains working with relatively lighter weights as with heavier. And for all the reasons discussed there, this makes starting lighter rather than heavier the most logical choice. The question then becomes how to choose a starting weight.

You will occasionally come across systems that recommend starting weights based on bodyweight (i.e. squat with 1/2 bodyweight or what have you). And I think this is a terrible approach for beginners. Actually I think it’s a terrible approach for everyone. Even if those values happen to represent some portion of beginning trainees, it can’t represent all of them. So don’t use those.

For me, taking a conservative approach is always the best. You can always add weight if it’s too light. But if you start to heavy, you can get into problems. You might get injured or get so sore you never come back for the second workout.

The first workouts should always be light with the focus on things like proper technique, breathing and movement speed. As a beginner you can’t focus on this if you’re also thinking about how heavy the weight is. And the weight can always be increased. For routines with multiple sets this might mean an increase from the first to the second set and the second to the third. For routines based on a single set, you start light and if it’s super easy, you increase at the next workout.

But that still doesn’t answer the question. And part of the problem is that the proper starting weight will depend a lot on who is being trained. A young male may be able to start at a much heavier weight than a young female or an older male or female.

For example, in the bench press, it would be unusual for a young male not to be able to start with a 45 lb bar. For many women, regardless of age, it would be an impossible starting weight and she might not even get one proper repetition. In many cases, I started women with as little as 5 lb dumbbells in each hand for a total of 10 pounds. And even that was often a bit wobbly. But I’d build from there. Commercial gyms usually have fixed weight barbells that start at 20 lbs and this may be an appropriate starting weight.

In contrast, if you’re looking at the squat, a 45 lb bar might be no problem for a young female. But for an older female trainee it may be far too heavy. Starting with a lighter fixed bar or even a goblet squat with a light DB might be a better choice. I think you get the idea.

In most cases, my general recommendation is starting with the lightest weight available on any given exercise while considering the exceptions described above. On a squat, the bar might be the right starting weight. On a leg press, start with the sled. On a machine leg press or chest press, start with one plate. Yes, it may be far too light. And?

If you’re only doing one set, go to two plates on the leg press or add 10 lbs to each side of the plate loaded leg press. If you’re doing multiple sets that day, add a bit of weight and see how it feels. Then add a bit more weight.

As much as I recommend starting light, I’d mention that sometimes an exercise that is too light can actually make it more difficult for the trainee to work on proper form. They can’t feel what they’re doing when it’s too light and it may take several workouts or sets to find an appropriate starting weight. That’s fine. This isn’t a race.

The Big Exception

There is one major exception to all of the above and this is exercises such as the deadlift or power clean where the weight starts on the floor. Here, to use proper technique, the bar must start at the proper height off the floor. Starting too low by using little plates or the bar alone won’t allow for proper technique to be used.

Now, in many commercial gyms, the only plates that will put the bar at the right height weigh 45 lbs. Two of those plus the bar is a starting weight of 135 lbs which may be beyond many trainees initial ability.

What are the solutions?

Gyms with an Olympic lifting focus always have bumper plates, special rubber plates that are meant to be dropped. And the nature of that sport is that all bumpers are the same standard diameter. Usually the lowest weight is 22-25 lbs but that still brings the starting bar weight down to about 95 lbs. Some gyms also have 10 lb training plates which brings the starting bar weight down to 65 lbs which can then be progressed by adding weight gradually to the bar.

But what if you’re in a gym that doesn’t have those? It is possible to get wooden training plates made but you have to find someone who can cut the wood into circles and put a hole in the right spot in the middle. They are also very fragile and there is a limit to how many plates can be added to them.

Failing that the trainee has to find a way to get the bar into roughly the same starting position as if it were in plates. This might mean using blocks or setting the bar into safety rack pins to put it at the right starting point. Weight can be added to the bar until the appropriate diameter 45 lb plates can be used.

Start Light Build Up

In any case, just to beat the point home, beginning weight trainers should always start lighter rather than heavier and then build up gradually over time. This isn’t a race and even if it takes 2-3 weeks to find an appropriate weight, one that is heavy enough to feel without being too heavy to lift properly, that is still time well spent. The trainee is still working on consistency, technique, etc. which is the more important goal anyhow.

Read A Guide to Beginning Weight Training: Part 6.

Facebook Comments