Continuing from Part 5, it’s time to finally wrap-up. Today I want to talk about progression in the weight room, when to add variety/make changes and then touch on when someone stops being a beginning trainee.

Table of Contents

Progression as a Beginner

So you’ve started now, hopefully light and building up. What happens next? Well the name of the game in improving any aspect of fitness is progressive overload. Over some time period, the training you’re doing now is no longer sufficient to make you get better. So over time you have to do more. I’m not saying this has to happen at every workout or even every week. It happens over time.

That more can take many forms. It could mean lifting heavier weights, it could mean doing more sets (up to a point), it could mean training more of often or increasing what is called training density. For the purposes of beginner training, we’re only interested in increasing volume (total number of sets/work done) and intensity (weight on the bar).

Which is going to be progressed as a beginner really depends on

- Your goals

- The program you started on

So let’s look at some examples.

My Basic Machine Program

So let’s consider my basic machine program, again really aimed at the general fitness and health trainee new to training. While I have allowed for the option of adding more sets, many will be happy performing only the one work set (in addition to a warm-up set later down the road). Here the goal would be to simply increase intensity, defined here as the weight being lifted.

If you look back at that program I gave a repetition range of 8-12 repetitions. What I’d tell them is when they get to 12 reps in good form without the last 2 repetitions being too much of a struggle, they should add a little bit of weight to the exercise. This might drop them to 8-9 proper repetitions and they’d build back up again. This is called a single progression system and it works really well at this stage.

But what if that trainee did want to increase volume? Well in the first week, as I described I’d have introduced them to the full set of movements. Four exercises the first workout, a few more the next, a few more the next. At that point, depending they might have done their second week of just one set and I’d add a little bit of weight as I saw appropriate.

In the third week, I’d have added a second set in the same order they introduced the movements. So first they’d do two sets of the first 4 exercises (leg press, chest press, row, crunch) then they’d add a second set of calf raise, should press and lat pulldown. Then maybe they’d stay there another week. Then they’d add 3 sets in the same way. I might even just stop them at 2 sets for arms due to the other exercises working those muscles indirectly.

So for the person wanting to do more than just the one se it might take up to 6 weeks to work up from 1 set of 8-10 exercises to 2-3 sets of those same exercises. At that point, the focus would be on increasing the weight being lifted over time.

But what about the other programs that start out at higher volumes.

5X5 Systems

In most 5X5 systems, the 5 sets are done by pyramiding up to a single top set of 5. And the goal over time is to add weight to basically every set so that everything keeps moving up gradually. So maybe at the first workout you go, 45,55,65,75,85 and that looks good. So at the next workout you go 50,60,70,80,90. Rinse and repeat.

Beginners can make a lot of progress for fairly extended periods of time doing this although eventually all good things come to an end. But let me mention again that it’s one thing to do the above when it’s being coached and another entirely when it’s not. Uncoached lifters doing 5X5, males moreso than females, tend to lift with their ego and not with their brain. They add weight every workout even if they aren’t ready and get into trouble.

My Mentor’s Barbell Training

My mentor took a little bit more conservative approach. His recommendation in terms of adding weight was this:

Don’t add weight to any lift until you can complete all of your sets while maintaining good form. It is normal while learning to have some wobbling, and it would not be unreasonable to stick at the same weights for a month (when you first start) before adding weight. You want to be in control. After you have that control, you should be able to add weight at least once per week.

Basically you keep it light until you get fairly stable and then increase the weights then. So you might spend the first month using the lightest of weights, even the bar in some cases. When technique started to stabilize, you’d add weight once/week (i.e. on Monday) and stay there for the week. Then assuming everything stayed stable, you’d add weight again on the following Monday.

My approach to barbell training is somewhere between the extremes of the 5X5 systems and my mentor. As I said, it’s possible for the weight to be too light for the trainee to really feel. In training a beginner on barbell movements, I would add small amounts of weight until the lifter could feel what they were doing. Then they’d settle in and not add much more weight until technique got stabilized. At which point it would be a more gradual progression.

Please note again the huge difference in uncoached and coached lifters. I can make judgment calls based on what I see that lifters can’t usually make on their own.

How Much Weight to Add?

The next question that comes up is how much weight to add to the exercise and you will find many different kinds of approaches to this. The problem being that it depends on factors such as age, the exercise and the weight being lifted.

A young male squatting 45 lbs might be able to jump by 10 lbs without problem. In contrast, a smaller woman benching a 20 lb bar might find a jump to 25 lbs to be overwhelming due to it being such a larger percentage of the weight being lifted. This is actually a problem that female lifters run into a lot, on many exercises the weight increase is a staggering percentage of what’s being lifted to begin with and the jump takes them from 10 good reps to zero.

The exercise in question also factors in although this is probably more of a function of the weight being lifted. Some squatting 135 lbs can conceivably add more weight to the bar than someone curling 65 lbs. Many would suggest a 10 lb jump on the squat and 2.5-5 lbs on the curl.

Older machines were particularly problematic and often increasing by a single plate meant adding 20 lbs to the stack. While this might be nothing to someone lifting 100 lbs, it would be a crushing increase to someone currently only lifting 40 lbs. Most newer machines allow for smaller weight jumps but sometimes you have to get creative.

In general, I still say be conservative. I would rather see someone add a “mere” 5 lbs to the bar at each workout and improve technique, conditioning, etc. then add 15 lbs to the bar and get ruined. In the beginner stage, it’s just not a race. Be conservative, build-up gradually and you’ll be stunned where you end up in 3 months. Add weight too fast and get hurt and you’ll be depressed at where you didn’t end up after 3 months.

When Progress Stalls

Gradual poundage progressions for beginners can work for a pretty long time, especially if they are eating well. Even so, eventually things stall out. I’d define this as a period of time where no progress in poundage or reps occurs for perhaps 2 full weeks. For a total beginner this might occur 3 or even 4 months in.

At this point, most systems will recommend a backcycle. This refers to an approach of dropping the weight back by 10-20% and then building back up again. So if someone had reached a point where they were back squatting 185X5 they would reduce the weight on the bar by 20-40 lbs to 145-165 and then start building gradually back up again.

By the time they reach their previous poundages in 3-4 weeks they will be stronger and should easily push past their previous best poundages until they stall again.

This has a huge benefit for the beginning trainee in that the reduction in weight allows them to focus that much more on proper technique under less than maximal loads. At this point their technique should be fairly stable but it will get even better when they can consolidate it for several weeks while building back up.

When to Make Changes/Variety for Beginners

So you’ve started a program and have been chugging along for a few weeks. The question then becomes when or how you should make any changes to the program. And while many will argue that a lot of variety is important for optimal performance (a debatable position to me), this is absolutely untrue for beginners.

Recall from Part 1 that many of the adaptations that the beginning trainee is looking for include general conditioning, neural adaptations and improving technique in the exercises being done. The reality is that these take time. This is especially true if you’re talking about technique for complex exercises.

Even if someone can become competent at them in weeks or months, they make take much longer to perfect (certainly this is less of an issue for simple movements). Doing this takes consistent regular practice.

Which is a long way of saying that beginners should actively avoid variety in their training, at least at the outset. If a trainee picks a set of movements and trains them for only a few weeks before deciding to “switch it up”, they will have barely made it through the neural and learning phases. If muscle goal is the growth, they are basically stopping the exercise right before growth might actually begin. And except for very simple exercises, they are nowhere near technically stable in anything complex.

Put differently, while variety can have some use, too much or too frequent changes in training almost invariably have a more negative than positive result.

General Health/Fitness/Machine Training

Now for trainees seeking general health and using something akin to my basic machine program, this isn’t as crucial. I could always teach basic technique in as few as three sessions since the machines are doing most of the work guiding the weight. In those cases, I might bring in a new exercise or two at about the 4-6 week mark. This was as much for mental variety as anything else. Crucially I only made a change to one of the training days at a time.

So if they were training Monday, Wednesday and Friday, I’d show them something new on Wednesday. Often it was slightly more complex exercise. So if they were doing all machines up to this point, or at least mostly machines, I would go ahead and teach them a free weight equivalent.

Once again recall the population that this program was typically used in, folks in their 30’s and 40’s with no real exercise background. My goal with their initial program was always immediate success and this meant staying away from anything that might cause them to feel awkward or embarrassed like complex movements. But by the time I considered bringing in other movements, they had established a base of training and were far more likely to succeed at them.

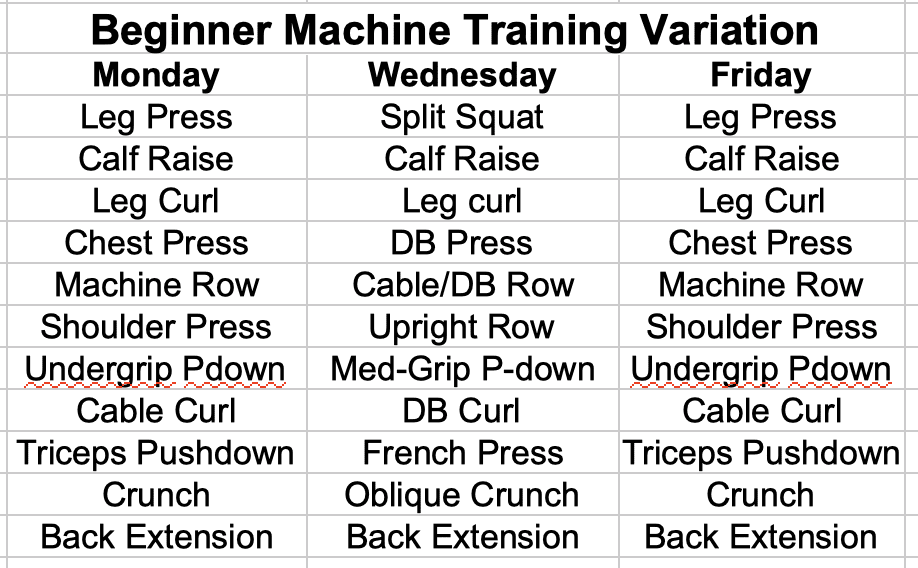

Depending on the specifics a machine leg press might become a free weight squat or maybe a split squat. Machine chest press might become a DB flat or incline press or flye. Rather than a machine row, I might teach a cable row or even 1-arm DB row. Overhead press would become a cable upright row or lateral raise. You get the idea. So their weekly schedule might now look like this.

These movements would always be brought in light at the first workout but they would continue working at the same intensity on the Monday and Friday workouts on the exercises they already knew.

This not only introduced a little bit of variety into their training and training week but gave them at least two options for any given muscle group. I felt this was important for long-term adherence.

That set of exercises would be maintained for another 4-6 weeks and I might show them a new movement. A lot just depended on the situation.

Barbell Routines

For anyone doing one of the barbell routines, I’d generally say to stick with the same set of exercises for at least 2-3 months, especially for the movements like squats, bench and deadlift. Fine if a trainee wants to do a different biceps curl one day, that’s fine. But the complex movements need to be maintained consistently to automate technique.

Most 5X5 variants are fairly fixed around their choice of movements and variations tend to be in the set and rep schemes. However, some of them usually allow for other movements to be added moreso than varied. I already commented on this, how I think one drawback of the strict 5X5 programs based around 3 movements is their lack of balance. Personally? I’d just bring in the other stuff off the bat.

I’d mention that Starr’s 5X5 approach often used quite a bit of exercise variety but this was more for intermediate and advanced trainees as part of a heavy, light, medium system. It wouldn’t be appropriate for beginners as too much exercise variety goes against the goals of motor learning, neural adaptations, etc.

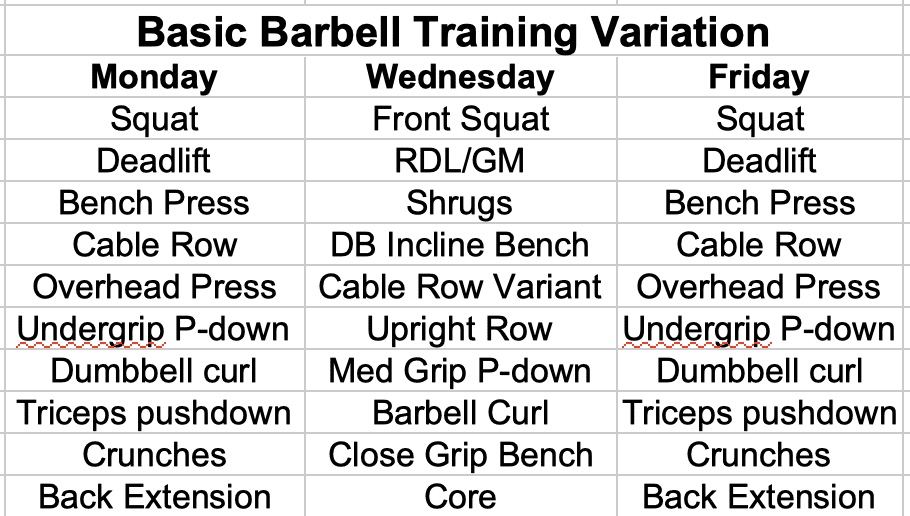

For something like my mentor’s basic barbell routine or my modification, I would generally approach it similarly to how I described my adjustments to the machine training. Specifically, after perhaps 3 months I might make slight exercise choice variations one one day per week (usually the middle day).

Front squat might replace back squat, I might consider a Good Morning to replace the RDL (if it were being done) or just bring in the RDL. At this point the trainee would likely benefit from only doing deadlifts 2X/week so I’d slot in shrugs on Wednesday. Not only does this introduce some new movements and a little bit of variety, it makes the overall workout more of a heavy, medium, heavy approach due to the generally lower weights that can be used on Wednesday.

If they were flat benching on Monday and Friday I’d do an incline variation, teach a different row, you get the idea. The goal would simply be to expose them to new movements while still maintaining consistent practice (and increasingly harder work) on the initial movements. So the new routine might look something like this.

And in another 2-3 months, there might be other substitutions.

Beginning Powerlifting

All of the above comments hold for a beginning powerlifting routine with even more emphasis on practicing the competition movements relentlessly to keep improving technique. Here any variations in exercise will be in the other stuff. Certainly this is a time to keep doing donkey work to build general strength and size. But the less complex of those movements can be rotated out safely.

Alternately, plugging in different movements on a Wednesday workout as described above would work. DB bench or machine chest becomes an incline variant, do a different row variant, I think you get the idea right now.

I suppose it’s possible that a beginner looking to add variety might add in a specific supplemental exercise for the main lifts but I’d consider that more of an intermediate approach. For the beginner wanting to powerlifting, focusing their energy on the competition lifts and general size and strength is generally the best approach in my opinion.

Physique Training

The same basic concepts from above hold here but, again recall the one goal of beginner physique training is to find exercises that fit the individual trainee. In that sense, introducing alternate movements at some reasonable frequency probably makes the most sense for this group. At the same time, you have to stick with the current set of movements long enough to establish if they are beneficial. And this is complicated by the fact that in beginners almost everything works to some degree.

But by the 2-3 month mark of consistent training, regardless of that beginner program, it will be time to replace some of the old movements with different movements. A flat chest exercise becomes an incline, a different type of cable or machine row or pulldown. The drill is always the same.

This allows the trainee to not only learn the new movements for future use but to evaluate them for their own benefit. Does the exercise allow the trainee to hit the target muscle effectively or not? If not, certainly movements may be eliminated. If so, they may be kept for the future.

And again all of this happens while the trainee continues to focus on good technique on the first set of movements, gradual progression in intensity/load on bar, volume or both, etc.

All of which leads up to the next and final question

When Do You Move to Intermediate Training?

At some point, all good things must come to an end and a trainee will no longer be considered a beginner. When does this happen? Well that can be difficult to pin down exactly. Some sources, focusing more on strength, will define it as when “you can no longer make strength gains workout to workout or week to week.” Which is at least semi-objective.

Others will put it in terms of duration. Above I laid out what amounts to two training blocks of 2-3 months, the cut being when you introduce new movements, so that is a solid 6 months of training as a beginner. I’d say this would be the minimum duration of consistent training before I’d consider anybody an intermediate. In some cases, trainees might go a year before they really need to make that change.

Simply using the approach of back cycling the weights by 10-20% and building back up when a stall occurs can get people pretty far for a pretty long time. Without making any major changes to the routines, that might get someone through a full year of training.

Even so, eventually that will stop working. If after a backcycle and build up phase the trainee doesn’t make it past their previous strength level, they will need to move to a more intermediate training approach.

Let me note again that “needing” to make that change and “wanting” to make that change are two very very different things. As I mentioned, beginners tend to fall into the trap of wanting to adopt advanced training styles right off the bat, usually mimicking whoever is at the top in their sport. And it’s not the right approach. If simple beginner training is still working, stick with it until it stops.

But what about when it does finally stop? It might be at the 6 month mark or perhaps the year mark. It doesn’t matter when it occurs so much as that it will and does occur. At this point there are a lot of options that would take another overwritten series to address.

For the person seeking general health and fitness, very few changes might be made. After a year of training, some nice strength gains along with some increases in muscle mass will have occurred and that might be all the person needs. Just maintaining that level may be fine. Alternately they might split their current workout into two parts to give themselves more weekly training flexibility.

For trainees with other goals, it’s fairly standard for training volume to be increased somewhat as they move into an intermediate stage of training. Certainly low volume routines can be used effectively but they require monster focus and intensity. An intensity some moving into the intermediate level might not have yet.

So increasing the total number of working sets is the common approach. That usually mandates moving to some sort of basic split routine. Otherwise the full body workouts that are currently being done become oppressively long.

And I do mean basic. The typical bodybuilder “bro” split where each muscle group is trained once weekly would be inappropriate. Instead I might recommend an upper/lower body split where each workout is done twice weekly. The splitting up into two parts will allow more total work sets (increasing from 3 to perhaps 6 initially and then to 8 a little bit later) and more than one exercise per muscle group. Few muscle groups need more than two at this point and one compound and one isolation movement per muscle group would be fine.

A powerlifter would move to something similar but the focus would be on exercises rather than muscles per se. The typical split would be a squat day (often with lighter deadlifts), a deadlift day (often with lighter squats) and two bench days (one of which may be lighter than the other). How the main movements are worked might change as well. Sets of 5 aren’t for everyone and there are a lot of different approaches that can work here.

At this point, an assistance or supplemental movement might be brought in if a weak point has been identified. The general donkey work would also be maintained. The goal even at the intermediate state is still technical skill development with most of the energy being put there. Starting to bring in movements that will be important later in their career is important too along with continuing to build a general base of strength and size.

But to detail all of those changes would take A Guide to Intermediate Training programs which I haven’t written yet.

Facebook Comments