Ok,it’s time to to finish my look at the fat free mass index (FFMI) so I can move on to something else whenever I get a bug up my butt to write again. In Part 1, I examined what the FFMI represents (ostensibly an indicator or screening tool for anabolic steroid use) along with some of the various criticisms that have been brought against it (revolving around late 19th century strongmen and some questionably natural Mr. Universe competitors).

In Part 2, I started with an addendum to Part 1, examining the simple fact that tesotsterone was synthesized in 1937, available by 1940, might have been mentioned in 1938 in the primary bodybuilding/fitness magazine of the time and was assuredly in use to some degree by the mid 1940’s. This raises severe questions about the claim that any top bodybuilders (including Grimek who had a supposed FFMI higher than Arnold’s in 1941) were natural.

Moving from there, I looked at a slightly different question which is the potential upper limits to fat free mass (FFM) in the human body. This entailed a variety of data points including sumo wrestlers, elite bodybiulders and Ray Williams. Finally, I did an analysis of top provably natural bodybuilders to show that less than half of the most elite get across the threshold (with the top 4 bodybuilders being black, possibly pointing to a systematic ethnic difference).

One topic I beat into the ground in Part 2 was that FFM can be skewed desperately up by carrying a pile of bodyfat. And that when you diet folks down, making some *rough* assumptions about FFM loss, their numbers come rapidly in line with the cutoff points.

I more or less summarized the topic then by saying that “No, the FFMI cutoff is not absolute, in that people have provably gotten across it.” but that “But it might as well be when you consider the absolutely inconsequential percentage of the total training population that can get there much less across it. If only 1-2% of trainees can get even to it or across it without anabolics, I can stay with some statistical certainty that if you did, you’re probably not clean. Will I be right 100% of the time? No. But I’d put money on it in most of those situations.

And I finished Part 2 by asking the question that I’m going to address today: is FFMI even the right metric to be examining in the first place? And to do that means returning to the poor dead horse of what FFM represents, although in a slightly different way.

Table of Contents

FFM or Skeletal Muscle: Part 1

I mentioned in Part 2 that all FFM is not skeletal muscle. Rather, FFM includes water, glycogen, minerals, bone and organs with skeletal muscle typically making up ~45% of total muscle for men or so and a little less for women due to having higher organ mass. And at the end of the day when we talk about the idea of an FFMI cutoff in terms of being natural or not, what we are really talking about is a limit to how much MUSCLE MASS can be gained naturally.

I mean, fine, FFM is FFM I guess which is why carb-loading or creatine loading or getting fat or whatever makes your numbers go up but is this what people really care about in this debate? And fine, we know that some of the rapid “FFM” gains with certain steroids is water and glycogen storage too (depending on the compound). But again is this what we are really talking about here? Water and glycogen or connective tissue and mineral FFM? I daresay not. That’s right, daresay.

What matters here is how much skeletal muscle is or can be gained with training with or without the use of steroids. And this brings in a couple of different issues.

The first is baseline FFMI (or FFM), that is a person’s initial FFMI before they start training. Because what we are really talking about here is how much of an INCREASE in FFMI can occur with training with or without drugs. It’s the same issue with how much muscle can be gained on top of where folks are after puberty.

Someone who is just a BIG KID who is 170 lbs after puberty who gets to 190 with training is still bigger than someone who started at 130 and gained 40 lbs to 170. The second gained more muscle but is still smaller because he started out smaller. The FFMI per se tells us nothing about what they might have individually gained.

And I bet if there was some way to use a time machine, the athletes with the biggest FFMI after training for a bunch of years, had the highest FFMI to start with. I’m willing to bet that Ray Williams was a BIG DUDE with a high FFM and FFMI before he picked up his first weight. He just got a LOT bigger from training. If you start big you end bigger.

The one paper I cited in the last part speaks to that. If a black athlete starts with a 1 point higher FFMI than a white athlete for some reason (and this could be differences in bone density or muscle mass or what have you), even if they both increase their FFMI by an identical amount (i.e. gaining identical amounts of muscle at the same height), the black athlete ends up with a higher FFMI. But the higher FFMI value per se says nothing about how much muscle they gained. It just says that if you start with a higher baseline, you end up at a higher final end value.

So I think the biggest issue is how much FFMI was gained past the starting point, not the absolute value reached. If someone starts bigger, they will probably end up bigger given the same training.

Starting and Ending FFMI

Here’s an odd older paper that I think relates to this. Titled Effect of body build on weight-training-induced adaptations in body composition and muscular strength. It recruited 77 non-training subjects (healthy clerks, although Smith, K is not on the author list) and grouped them into either a slender or solid build based on their FFMI. A fairly generic full body weight routine was given twice per week for 12 weeks and body composition changes were examined.

Now the mean gain in LBM was 0.9 kg (about 2 lbs) but there were major differences between groups. Specifically, the slender group only gained 0.3 kg (about 2/3rds of a pound) of FFM while the solid group gained 1.6 kg (3.5 lbs) of FFM (both groups lost fat which throws in a diet confound but no matter). This led the researchers to conclude

After 12 wk of weight training, individuals with a solid body build increased their FFM whereas slenderly built individuals did not show a significant change in FFM.

Perhaps there is something to the Hardgainer idea, eh? Or somatotype perhaps? And yes, this probably just means that a slender individual needs to train differently for optimal results but that is not the point of this digression.

Of interest were the initial FFMI values which were 17 for the slender group and a whopping 22 for the solid group with the initial FFM values being 55.9 and 69 kg respectively. The solid group was starting with 13 kg (28.5 POUNDS) more FFM. Heights were no different so presumably bone, organ mass, etc. was nearly identical. That would suggest that they were naturally carrying that much more muscle to begin with (hence a solid build and again these were non-training subjects). Admittedly body fat percentage was in the 24% range but still, that’s a big difference (diet them down to 12% so some of the non-muscle FFM comes off and the values drop).

So imagine that both groups gain 10 kg of muscle/FFM in a year of good training. The FFMI values go to 20.3 in the slender group and 25.2 in the solid group. By dint of starting out high, the solid folks break the cutoff with a fairly decent muscle gain (perhaps one year of proper training for a newbie). With another 10 kg gain (20 kg or 45 lbs total over the next several years), they go to 23.4 and 28.4 (note again: this would be lower when you leaned them out). By dint of starting with more FFM and a higher FFMI, the solid group surpasses the cutoff and this is despite gaining identical amounts of muscle.

But let’s imagine that the slender group manages to gain 20 kg of muscle while the solid group gains only 10kg (45 vs 22 lbs) perhaps because they have less room to grow or something. This takes the slender group to an FFMI of 23.4 while the solid group hits 25.2. The slender group gained more muscle but their FFMI is still lower due to starting at much lower place. Think of the skinny ‘hardgainer’ who starts training versus the guy who starts out bigger naturally. The first can gain far more total muscle and still end up smaller and a lower FFMI just because they started so much lower/smaller.

And, again, I bet that the guys hitting the highest FFMI values I’ve discussed in this series also started with higher FFMI values so of course they ended up higher and/or crossed the supposed natty cutoff point. But it had nothing to do with being natural or not. It had to do with simply starting out from a higher baseline. Start bigger, end up bigger. Seems fairly simple and I bet neither Ray Williams nor Nisma were small when they began training. They started big and ended up enormous.

FFM or Skeletal Muscle: Part 2

But there is another issue that ties in with this which is, again, we are interested in skeletal muscle changes and that only makes up a proportion of LBM. As I’ve repeated rather endlessly, with increasing bodyfat comes increasing LBM even if muscle mass per se isn’t going up.

Khouri et. al. acknowledged this in their first paper and I discussed it when I talked about the Sumo wrestlers and Ray Williams and all of the “But football players have more muscle” arguments. The non-muscle connective tissue, etc. FFM can skew FFMI up but shouldn’t really count the question of natty or not. Diet them down, up to 25% of it comes off and their FFMI comes way down, much closer (but often still exceeding) the cutoff.

But now I want to look at that issue a bit more formally, by examining the paper that reminded me that I wanted to write about this topic again. It was one referenced at me in another attempt to disprove the FFMI cutoff (by the same vocal critic who failed to cross the FFMI himself as per my Part 2 analysis, told you I was a petty prick). It was also one that I meticulously analyzed in my FB group and the one that reminded me to write about this again to get it out of my brain (don’t worry, when my brain is dumped, these articles will stop).

Correction to the Original Article

While it’s not uncommon for people to re-read my articles (who might notice the change) , I still want to make this very explicit for anybody reading this series. In the original version of this article, the section you’re about to read contained a fairly major mistake. Detailing the original analysis isn’t that critical, the point is that it was wrong. Greg Knuckols was the one who brought it up (though in a very different context and for a very different reason that is of no relevance here) and, as much as I hate to admit it, he was right.

Now in one sense, it didn’t matter as nothing in that section changed a word of my overall conclusion of the series. I could have deleted it and a later section and, really, deleted about this entire third part of the article and nothing would change. It was just a weird side digression that changed nothing.

But that would be intellectually disingenuous because it would look like I’m simply trying to hide my mistake. I think it’s important from an intellectual honesty standpoint to both make my mistake explicitly clear as well as correcting it. This is a behavior that seems to be in short supply in this industry and perhaps I can lead by example. Simply, when you make a mistake, acknowledge and fix it. Don’t deflect with weaksauce arguments and then block the critic…..

Now, I am still going to look at this paper because I still think it still slots into the overall thesis of this series. It’s just a way of looking at the issue in terms of skeletal muscle per se rather than total FFM. As well, since there is no practical way of measuring SMI at this point, it is really pointless to even examine. But I must forge ahead.

Let’s Talk about Skeletal Muscle

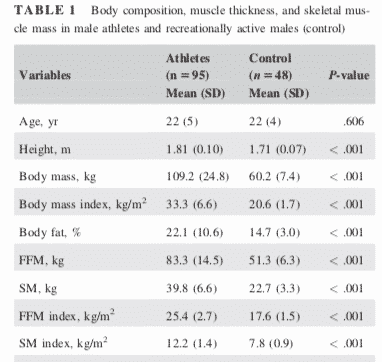

The paper I want to re-examine is titled Skeletal Muscle Mass in Human Athletes: What is the Upper Limit by Abe et .al. and published in the American Journal of Human Biology. In it, 95 male athletes (43 American college football players, 18 powerlifters, 28 college sumo wrestlers and 6 shot putters) and 48 recreationally active males were recruited for the study and a variety of measures of body composition were made for comparison purposes.

The football players competed in Division 1 NCAA and the other athletes competed at the national and international level. Oh yeah “None of the subjects reported taking anabolic steroids.” And well, does anybody actually believe this? If so, please contact me about a bridge (I’ll throw in an ostrich farm while I’m at it). Because there is simply no way this can possibly be true.

Steroids have been part of football for decades, including at the collegiate level. The same holds true for basically any national or international level athlete because the reality of modern sport is that you don’t get to that level without them. And I think that anybody who thinks even a majority of these guys are clean is delusional.

So I think all of the subjects were using? Probably not and I won’t copout and say they were. But if you think that their self-reported non-use is trustworthy, you can’t be helped anymore than the person who cited this at me. People lie, athletes really lie about steroid use (even when they are given anonymous surveys) and I don’t believe for a second that these guys were all clean. You can disagree if you want, but you’ll be wrong.

Regardless, for all subjects bodyfat percentage was made by underwater weighing so that calculations of fat mass and FFM could be made. As well, muscle thickness was measured by Ultrasound at 9 sites (again raising issues in my mind of why all these stupid volume and hypertrophy studies tend to only do biceps and triceps and quads instead of measuring more relevant muscle groups but I digress).

Importantly, these measurements were used to estimate total Skeletal Muscle Mass (SM), that is the total amount of actual muscle mass the athlete was carrying. As I’ve mentioned, muscle mass is only a proportion of total FFM, making up ~45-50% on average in men (it’s a little lower in women). This was used to calculate a Skeletal Muscle Index, defined as skeletal muscle divided by height squared. This is an identical concept to the FFMI (or even the BMI), just specific to skeletal muscle rather than the total FFM (or total body weight in the case of BMI).

The SMI tells you the actual amount of MUSCLE MASS (rather than gross FFM)

relative to height that someone is carrying.

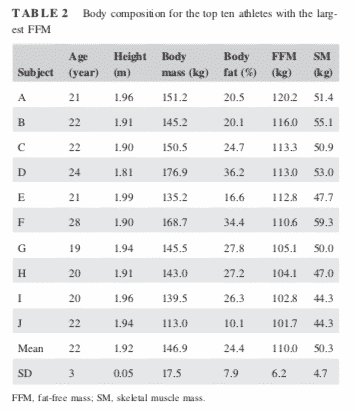

To no one’s surprise the athletes were bigger than the recreational males with both FFMI and SMI being higher by about 8 and 4.5 points respectively. Importantly, 10 of the athletes had more than 100 kg FFM (the largest at 120 kg) with seven athletes having more than 50 kg actual skeletal muscle (the highest value being 59.3 kg). The 10 biggest guys, outliers from the main group with the highest FFM appear in the chart below.

Now it was from this chart that I originally made my arguments about FFMI and SMI frequently having no real relationship. That analysis was incorrect so I want to look at it a bit differently. To do that, I want to look at both the individual data above along with the data for the mean of all athletes. Note that the group mean includes the above 10 outliers who are likely pulling the numbers up a bit. Since it’s only 10 of 95 total athletes, I don’t imagine the impact is that large but no matter.

Now it was from this chart that I originally made my arguments about FFMI and SMI frequently having no real relationship. That analysis was incorrect so I want to look at it a bit differently. To do that, I want to look at both the individual data above along with the data for the mean of all athletes. Note that the group mean includes the above 10 outliers who are likely pulling the numbers up a bit. Since it’s only 10 of 95 total athletes, I don’t imagine the impact is that large but no matter.

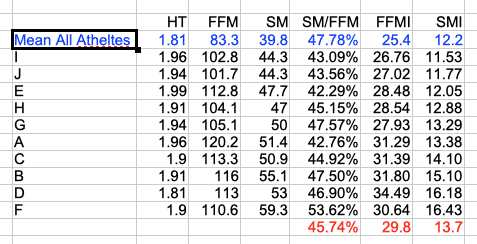

In the chart below I’ve included height, FFM and SM for the mean of all athletes (I simply used the mean values for the group) along with the specific values for the outliers. For each I did three calculations. The first is SM/FFM, the ratio of skeletal muscle to fat free mass; this indicates what percentage of the total FFM is actual muscle. I also calculated the non-normalized FFMI and SMI. Yes, athletes is misspelled.

The top line in blue represents the data for the entire group of athletes with the individual outlier athletes listed below in order from lowest SMI to highest (the letters match the data from the chart above). In red at the bottom I’ve averaged the SM/FFM, FFMI and SMI for the 10 outlier athletes only.

So what do we see? For the overall group of athletes, FFMI is just above the proposed cutoff of 25 (25.4) with an SMI of 12.2. Also, the SM/FFM ratio is 47.78 which falls exactly in the range of 45-50% I’ve mentioned repeatedly.

So now let’s look at the outlier athletes for whom there is a much larger range. The average FFMI is a whopping 29.8 with a range of 26.76 to an incredible 34.49, all exceeding the proposed cutoff of 25 along with the group average. One thing to note is that, with two exceptions, the body fat percentage on the athletes was fairly high ranging from 20-36% (one athlete was 10.1% and one was 16%). As I’ve noted repeatedly, this can skew FFMI up due to water, glycogen, connective tissue and non-skeletal muscle FFM increasing simply due to fat gain.

Now, I could probably attempt to do the same back of the envelope calculations to determine their FFMI if they were dieted down but I’m not going to and I’d making far too many assumptions for it to mean much. As importantly, even if the FFMI came down with a diet, assuming skeletal muscle wasn’t lost, the SMI wouldn’t change.

Since my focus is on SMI here, there’s no point in even attempting to do the calculation. Even in this vein, I think the SMI makes a better metric than FFMI. FFMI can be skewed artificially up and down by non-muscle FFMI but the SMI can’t. What changes, rather, is the percentage of skeletal muscle that represents FFM. I hope that makes sense.

The average SMI is 13.7 but this ranges from a low of 11.53 (lower than the group average) to a huge 16.43. That value is in Athlete F who is an absolute freakshow, an outlier among outliers. He has not only the highest amount of skeletal muscle by far (nearly 10 lbs more than the next biggest athelte), his ratio of muscle to FFM is 53.6% meaning that more than 50% of his total fat free mass is muscle. The second highest value is 47.57% so the dude is just an outlier among outliers.

Finally for the ratio of SM to FFM, the average is 45.7%. Like the average of all athletes, this is right in the 45-50% range so this passes the reality check. The range is high though from a low of 42.29% (meaning that a much larger proportion of this athlete’s FFM was non muscle) to the freakshow athlete at 53.6%. Take the freakshow guy out of the average (not shown) and the value drops to 44.86% due to multiple guys having less than a 45% ratio. This is close enough for government work.

So what does this all mean? Well not much probably since it doesn’t say that much more than just the FFMI does. As Greg was happy to point out, there is a strong relationship between the FFMI and SMI with a high FFMI being generally predictive of a high SMI. Yes, there’s slop, if two athletes had the identical FFMI and one had the low 42.27% ratio and the other the 53% ratio of muscle to FFM we’d have some distinct SMI values. But that might not be something that really occurs in the world. On average, a high FFMI and high SMI go fairly well hand in hand.

Which doesn’t mean that you couldn’t propose an SMI cutoff (just like the original FFMI cutoff) above which steroids were implicated. We might roughly assume it’s about 12 or so based on the group mean but, hell, if you just multiply a cutoff of 25 times an assumed 45% skeletal muscle you get 11.25 to begin with. Multiply by 50% and it’s 12.5. Split the middle and you get 11.875. An SMI of 12 is good enough for government work. We might get pickier and take the group mean of 12.2. This is nitpicking.

That value is consistent with the first 3 outliers but the remaining 7 exceed it. I will still contend, given the nature of the population studied, anabolic steroid use is likely part of the picture. Even if they are clean, they represent 7 outliers among a population of 95 high level athletes. They are the exceptions in every way.

And they represent an inconsequential number in the big picture. Sure there are a LOT of athletes and some proportion of them are probably above the cutoff. Sports also represents the best of the best and there is always the spectre of steroid use. I don’t think a handful of exceptions mean much to the average weight training individual. You’re not an elite athlete, you don’t have their genetics or their gear and you’re likely not hitting that FFMI or SMI cutoff.

As was my original point, I’d still contend on a base level that SMI is a more accurate metric than FFMI per se since it will be relatively unchanging even if FFMI is impacted by non skeletal muscle fat free mass changes. Given that SMI is impossible to estimate and FFMI and SMI show a strong relationship, it really doesn’t matter. Like I said, this section was just a digressionary sidebar that didn’t change anything in the big picture of what I was trying to discuss or argue.

At most, all this points out is that, sure, there are athletes who provably surpass the FFMI cutoff of 25. And it represented all of 10 athletes (yes, there could have been a few more but individual data was NOT provided) out of 95 at the elite level.

I still do not see this as compelling evidence although I thought it was important to address Greg’s criticism and make a correction to the article on fundamental grounds of integrity and intellectual honesty. As I said above, far be it from me to ignore data to draw an incorrect conclusion. But my correction really doesn’t change anything. I was simply correcting it on the principle of being intellectually honest. More in the field should try it.

How Much MUSCLE Can You Gain?

And, as above, what we care about is not FFMI per se but rather how much muscle someone is carrying or, more importantly, how much can be realistically gained with or without steroids. In this vein, I have one last point, sort of an accidental observation from the same paper. Her I am looking at the overall data from the above study by Abe et. al. The chart below compares the athletes to the recreational controls.

Again note that the mean of the athlete’s FFMI was 25.4 (gee that’s a real familiar value) although 10 clearly exceeded that. I really wish they had indicated what sport each of the 10 athletes was in since that alone would have been super informative. So would ethnicity.

But more importantly look at the skeletal muscle mass numbers. It’s 22.7 kg in the controls and 39.8 kg in the well trained athlete, which is a 17kg or 37.5 lbs. And that is a vaguely familiar number, certainly similar to what I’ve proposed as an upper limit on muscle mass gain in naturals something like 15 years ago based on an average gain of 20-25 lbs in year one, 10-12 in year two and 5-6 in year three (of proper training and eating of course). That yields a potential 40-45 lbs over a career but that’s the absolute high end. And it’s just a little bit higher than the difference between the trained athletes and the non-athletes.

So if you train for 3-4 years properly and have good genetics and a little luck you might gain 17-20kg (37-45 lbs) of total skeletal muscle from where you started and that’s all you’re getting. Gaining more actual muscle than that means taking anabolics in most situations.

Where that puts your FFMI at that point depending on your height, starting point and how fat you get with the SMI being far more relevant anyhow. If you started with a high FFMI and gain that amount of muscle, you end up with a very high FFMI. Start with a low FFMI and you don’t.

AND THIS IS TRUE WHETHER YOU ARE NATURAL OR NOT.

The FFMI ending point simply doesn’t matter in terms of how much actual muscle you gained because it can’t tell us that. But that amount of muscle is likely to tell us whether you’re natural or not. Because if you gained 30 kg of muscle, 66 lbs, I can say that either you are a 1 in 10,000 exception (or whatever) or that you’re not clean.

Ok fine, someone will bring up ANOTHER strawman about some scrawny underfed kid who went from 120 to 180 during puberty and, good grief, why do I have to keep qualifying this stuff when we all know what I’m talking about?

And this is true regardless of what your FFMI is or is not when you get there. Because the total amount of post-pubertal muscle you gained when you started training is going to be a really good indicator of your natty or not status.

And then looking past that observation, we have 10 athletes who have an additional 10-20 kg (20-40 lbs) more skeletal muscle mass than the average with 50-59 kg for the outliers vs. 39.8 kg for the group mean. And who I would still argue were all or mostly using anabolics. Once again perhaps this represents my bias.

But do you honestly think good training and eating is getting that extra 20-40 lbs of muscle over what the other athletes got? Do you think Grimek was bigger than Arnold naturally when testosterone just happened to have become available a year prior?

Bhasin showed that a baby dose of 600 mg of testosterone per week put 8 kg of LBM on guys with minimal training which would explain just less than half of that 20 kg difference. With 600 mg/week being an absolute baby dose of steroids in the modern era. It wouldn’t be that hard to find that extra 10-20 kg of muscle on the top guys if they were using anabolics at even a moderate modern dose.

And that would easily explain those athletes and why they carry so much more muscle but also have such higher FFMI and SMI. Start big with a high FFMI, gain about the maximum amount of natural muscle mass of roughly 20 kg, add another 50% to that with steroids and you end up with an amount of skeletal mass unachievable in 99.9% of naturals and an FFMI that far exceeds the 25 cutoff. Proving nothing about the cutoff point except that it can be exceeded if you start big, got bigger and got juiced.

Back to my Bodybuilder Analysis

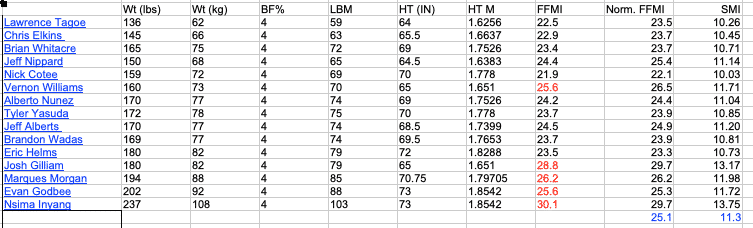

Having looked at the Abe paper, I want to see how those numbers scan with the cohort of top bodybuilders. So I’ve redone the same analysis as before, but with an additional calculation for SMI. Here I had to make an assumption which was about the ratio of skeletal muscle to total FFMI. In the original analysis I did I assumed 50% for no real reason other than 1) it made the math easy 2) I felt it was a safe assumption given that competition bodybuilders are dieted and dehydrated to such a degree that their relative proportion of muscle to FFM is likely to be high.

For this redone analysis I figured it was reasonable to just use the mean percentage from the Abe study which was 45.7% representing the mean of the 10 outlier athletes. Is this right, wrong? Would the 47.8% of the group mean have been better? I have no idea and I don’t think it matters that much since I used the value consistently. I’d love to see data on it.

So this is just the same list of bodybuilder data as before with an estimated SMI based on an assumption of 45.75% of their total FFM being actual skeletal muscle. What stands out is that the SMI values are systematically lower than the Abe study. The average is 11.4 (range 10.26 to 13.75) compared to the mean of 12.2 in Abe for all athletes and 13.7 for the 10 outliers. This goes along with the stock average FFMI of 25.1 (range 22.1 to 29.7) and, as I mentioned above, with an assumption of 45% actual skeletal muscle, a 25 FFMI cutoff ends up at 11.25. So of course that average FFMI yields that average SMI.

So this is just the same list of bodybuilder data as before with an estimated SMI based on an assumption of 45.75% of their total FFM being actual skeletal muscle. What stands out is that the SMI values are systematically lower than the Abe study. The average is 11.4 (range 10.26 to 13.75) compared to the mean of 12.2 in Abe for all athletes and 13.7 for the 10 outliers. This goes along with the stock average FFMI of 25.1 (range 22.1 to 29.7) and, as I mentioned above, with an assumption of 45% actual skeletal muscle, a 25 FFMI cutoff ends up at 11.25. So of course that average FFMI yields that average SMI.

As above, it might be better to assume, given their dehydrated state, that 50% of these bodybuilders total FFMI is skeletal muscle. If I remath it (not shown), that takes the mean to 12.4. This, of course, is just what you get with an FFMI of 25 and assumption of 50% muscle more or less (12.25). The difference is the two crazy outliers and other few who exceed that who pull the average up a little bit. At this point we’re picking nits.

So I’ll just say that the equivalent SMI of the 25 FFMI cutoff point for naturals is somewhere in the realm of 11.2-12.4 (depending on your assumptions about the skeletal muscle percentage). As noted earlier in this series, I consider the list of bodybuilders above to be provably natural, at least within the limits of what is provable.

I’m still not playing the copout game and defining anybody above the cutoff as using. Similarly I still contend that the athletes in the Abe study are more likely to be using than not. Not all of them but enough of them and likely many of the outliers. Athletes simply don’t get to that level in elite sport clean.

Regardless, with an SMI cutoff of 11.2-12.4 and an assumption of 45% for skeletal muscle, the same 6 athletes get across : Jeff Alberts (11.2), Vernon Williams (11.71), Evan Goodbee (11.72), Marques Morgan (11.98), Josh Giliam (13.17) and Nsima Inyang (13.75). Alberto Nunez (11.04) and Jeff Nippard (11.14) fall just short. That same vocal critic of the FFMI concept doesn’t even crack 11 if we assume 45.75% total muscle mass. Yes, their SMI values go up if we assume 50% muscle mass but so does the average cutoff point and it all balances out.

So again what does this tell us? Or at least suggest? Well, that just as with FFMI, it’s clearly possible for provably natural individuals to exceed any semi-reasonable proposed limit. And they still number in the handful. Six of fifteen elite bodybuilders with 2 more super close and the other 7 not getting there. It’s still an inconsequential number (like I said, nothing about how I first examined the Abe et. al. remotely impacts on my overall conclusion) so far as I concerned.

I want to note again that the entire rewriting of this analysis did NOTHING to change my conclusion. Yeah, I was still wrong and Greg was right. And my conclusion is IDENTICAL. I just believe in correcting my mistakes when they are pointed out to me because that’s the intellectually honest thing to do. And speaking of conclusions, here it is. Exactly one paragraph changed slightly due to my correction of the SMI thing but again, it was immaterial in the big picture.

Summing Up the FFMI Issue One More Time

So let’s see if I can sum all this nonsense up and beat this dead horse one last time:

In 1995, research suggested that an FFMI cutoff of 25 existed and that ANYBODY above that was using steroids (rather it could be a screening tool for steroid use). In is popular book, Pope apparently took this further but I never read it so I can’t quote what he may or may not have said.

In an absolute sense this is clearly untrue. A small small small approaching irrelevant percentage of individuals who are provably natural have exceeded that in various contexts. Depending on your assumptions it might be as much as 1% or a little bit lower or higher. Maybe it’s higher if you start looking at elite athletes who reach the top.

But since this doesn’t represent the majority of general trainees, it’s no more relevant. But it a tiny percentage of all individuals trying to gain muscle which is the real point. It’s ultimately insignificant in the big picture. Exceptions are only that and, statistically, you’re not in the 1-2% who are the exception. You’re not in the 10% of exceptions if they number in that range. That’s not how this works.

Even here, a majority of the exceptions that people have trotted out are questionable as hell. Late 19th/early 20th century strongman when nobody kept good records and guys exaggerated? Just about any bodybuilder after 1940-1945? I was able to find more exceptions, Sumo wrestlers, Ray Williams, a handful of what I truly believe to be natural bodybuilders. We’ve got a few dozen examples against the zillions of males lifting weights. Yeah, this isn’t a compelling argument to me: the exceptions prove the rule so far as I’m concerned.

There may be a link between ethnicity and all of this. Based on an excruciatingly small sample size, it would appear that black athletes are slightly more likely to exceed the 25 cutoff than whites (due to starting a little higher) and it would be interesting to see if there is some higher cutoff that applies here . It needs to be studied systematically. Based on nothing but my pure speculation/observation, it would not surprise me if there were additional regional/ethnic differences (i.e. Island Somoa or Tonga or those big ass Norwegian ver Magnussons).

The fact that there are an insignificant (in the big scheme) number of exceptions, somewhere between less than 1% to *maybe* 1-2% if you’re generous, that cross the 25 FFMI cutoff doesn’t disprove or dismiss the idea that a cutoff exists. Rather, it makes the following point:

From a practical standpoint, it might as well be an absolute cutoff.

Because realistically, you aren’t part of the 0.1-1/2% who will get across it naturally. Not unless you started big and muscular with a high FFMI and just got bigger and more muscular from there. Again, if I told you you had a 1-2% chance of walking into freeway traffic and surviving, would you bet that you would live? I’d put money that you wouldn’t with some degree of certainty. Same thing here. I can’t say for sure that anybody above the FFMI cutoff is using but I’d probably put money on it that they were. And I don’t take bets I don’t think I’m going to win.

In a conceptual sense, FFMI is probably the wrong metric to begin with. Yes, Kouri even acknowledged that it wouldn’t hold for individuals carrying a lot of fat but this seems to have been missed in a lot of the discussion. Athletes can clearly have massive amounts of LBM with a high FFMI but a large percentage of that will be non-muscle tissue. Diet them down and FFMI comes back to near/essentially normal levels with even fewer examples of folks who are much higher than this value. What did I come up with, like 5 who significantly surpassed the FFMI value clean?

Because at the end of the day, nobody reading this gives the first damn about FFM that isn’t skeletal muscle. You can get a higher FFMI by getting big, fat and water-logged and taking creatine and carb or salt loading. Folks with Cushings have a staggering FFMI due to holding gallons of water due to cortisol overproduction. That is not relevant to either the FFMI concept of whether or not someone is using drugs. It is simply not what is being discussed or argued about to begin with.

What we care about is how much muscle someone is carrying and/or has gained over their career. Because, as much as people don’t want to accept it, there are some pretty strong limits on how much muscle mass can either be gained or carried naturally. The bodyweights in natural bodybuilding competitions have not changed for decades (at most there are a handful of in shape super heavy weights) while pro bodybuilders continue to get bigger and bigger due to the use of more drugs.

Those limits can only be surpassed with the use of anabolic steroids and you simply cannot get around that fact no matter how much it pains you. Training properly, a male might gain 10-12 kg/20-25 lbs of muscle in their first year, half that in their second, half again in their third and microscopic amounts from there on out for a total of ~18-20kg/40-45 lbs. That’s at the higher end. Most won’t even gain that much.

In that sense, the SMI is probably a much better indicator on all of this since it represents the amount of actual muscle mass relative to height since it actually can tell us how much muscle mass someone is carrying or gained since it’s their actual skeletal muscle. Yes, FFMI and SMI show a strong relationship but it can get skewed at the individual level.

SMI is also not impacted by any of the factors that impact FFMI like creatine or carb-loading. If you’ve got X lbs of skeletal muscle and I put 10 lbs of water on you with a carb-load, your FFMI goes up but you’ve got the same X lbs of skeletal muscle. Since SMI can’t be measured at this time, it’s an irrelevant digression for now.

The bottom line in my opinion: ignoring whether or not FFMI is the relevant metric, the handful of exceptions to the 25 cutoff (for whites anyhow) don’t mean a thing in the big picture. You’re not running a 10 second 100m, you’re not going to squat what Ray Williams squats and you’re most likely not getting past an FFMI of 25 (assuming you even get close) without drugs. Put differently:

Exceptions to a rule are only that and most people aren’t exceptions because that’s not what the word means.

Because with enormous statistical certainty, based on the realities of human physiology, genetics and statistical realities, not only can I say that any given individual will NOT surpass the 25 FFMI cutoff without drugs, I can say that anyone who did surpass it used drugs. I will be wrong in an insignificant number of cases. But it’s still a bet I’d take.

And that dead horse is beaten. And corrected. Thanks, Greg!

Facebook Comments