In recent years, the Internet has gotten a bit crazy for high-intensity interval training, proclaiming it’s superiority overall other forms of conditioning training. And while HIIT can take many forms, one popular one, wholly misrepresented in the fitness industry is what is called the Tabata Protocol.

This describes a very specific approach to HIIT created, originally for speed skaters, by an author named Tabata. Hence the name. It’s even been studied and it is this study that I want to look at today.

Table of Contents

HIIT and the Tabata Protocol

The concept of HIIT is fairly general, it describes a method of training where short periods of near maximum training lasting 15-90 seconds (with some variance) are alternated with periods of low intensity activity for some number of rounds. HIIT protocols are effectively endless in how they can be set up and few have a specific name given to them.

The Tabata Protocol is different. This describes a very specific type of training, defined below, which has been shown to generate certain adaptations which I’ll also discuss below. And one of many problems is that this very specific protocol has been bastardized, with similar looking training approaches often being called Tabatas.

And basically a lot of people are using this term or thinking they are using the protocol when they actually have no clue what they are talking about. What has happened is that a bunch of people who don’t really know what they are talking about have written so much about the protocol that what it actually is or accomplishes has been completely diluted.

So I figured I’d undilute it by actually examining the study that the whole set of claims and supposed ‘protocols’ are based on. Because, as is so often the case, what people think they are doing as ‘Tabatas” are nothing like what the actual study did or the actual protocol describes. And most people who think they are doing the Tabata protocol are doing absolutely nothing of the sort.

As I mentioned above, the protocol was actually originally developed by a Japanese speed skating coach and later studied by researchers, I bring this up because speed skating is actually a very peculiar sport in a lot of ways (something that I have insight into as I spent 5.5 years training full time as a skater). But I’m not going to get that into detail here; I simply mention it for completeness.

The Tabata Study

The study set out to compare both the anaerobic and aerobic adaptations (in terms of one parameter only, VO2 max) to two different protocols of training. The study recruited 14 active male students who were, at best moderately trained. Their VO2 max (one of several predictors of endurance performance) was 50 ml/kg/min which is average at best. Elite endurance athletes have values in the 70-80 range).

All work including the pre- and post tests were done on a mechanically braked bicycle ergometer. Just think of it as a stationary bike. This is an important point that is often ignored and I’ll come back to in the discussion. Every test or high-intensity workout was proceeded by a 10 minute warm-up at 50% of VO2 max (which is around 60-65% of maximum heart rate).

The two primary tests were VO2 max and the maximal accumulated oxygen deficit (MAOD). MAOD is just a test of anaerobic capacity. People with a higher capacity can generate a larger oxygen debt. After testing, subjects did one of two training programs.

The Aerobic Training Program

The first program was a fairly standard aerobic training program, subjects exercised 5 days/week at 70% of VO2 max for 60 minutes at a cadence of 70 RPMs for 6 straight weeks. The intensity of exercise was raised as VO2 max increased with training to maintain the proper percentage. VO2 max was tested weekly in this group and the maximal accumulated oxygen deficit was measured before, at 4 weeks and after training.

The Tabata Protocol Training Program

The second group performed the Tabata protocol. For four days per week they performed 7-8 sets of 20 seconds at 170% of VO2 max with 10 seconds rest between bouts, again this was done after a 10 minute warm-up. When more than 9 sets could be completed, the wattage was increased by 11 watts. If the subjects could not maintain a cadence of 85RPM, the workout was ended.

Let me make it clear that this IS The Tabata Protocol. It is 7-8 sets of 20 seconds of maximum work at 170% of VO2 max with 10 seconds rest between bouts after a warm-up. Anything that is not exactly that is not a Tabata and I’ll come back to this below.

On the fifth day of training, they performed 30 minutes of exercise at 70% of VO2 max followed by 4 sets of the intermittent protocol and this session was designed to NOT be exhaustive. So they did the full Tabata protocol 4 days per week along with one short aerobic session and a non-exhaustive partial Tabata workout.

The anaerobic capacity test was performed at the beginning, week 2, week 4 and the end of the 6 week period; VO2 max was tested at the beginning and at week 3, 5 and the end of training.

The Results

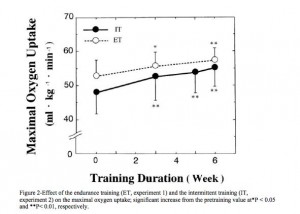

For the standard aerobic training group, while there was no increase in anaerobic capacity, VO2 max increased significantly from roughly 52 to 57 ml/kg/min. I say roughly as the paper failed to provide the actual values and I had to sort of eyeball it from the data I’ve below. Frankly, given the lack of anaerobic contribution to steady state training, the lack of improvement in this parameter is absolutely no surprise.

For group 2, both the anaerobic capacity and VO2 max showed improvements. VO2 max improved in the interval group from 48 ml/kg/min to roughly 55 ml/kg/min (see graphic below). While it wasn’t statistically significant the Tabata group was starting a little bit lower and may have had more room to improve. They also ended up a little bit lower although that difference was also not statistically significant.

So you can see the results from above, both groups made improvements in VO2 max. But note the pattern of improvement: the Tabata group got most of their improvement in the first 3 weeks and far less in the second three weeks. The steady state group showed more gradual improvement across the entire 6 week period but it was more consistent. As the researchers state regarding the Tabata group

After 3 wk of training, the VO2 max had increased significantly by 5+-3ml.kg/min. It tended to increase in the last part of the training period but no significant changes [emphasis mine] were observed.

Basically, the Tabata group improved for 3 weeks and then plateaued despite a continuingly increasing workload. I’d note that anaerobic capacity did improve over the length of the study although most of the benefit came in the first 4 weeks of the study (with far less over the last 2 weeks).

My Comments

First and foremost, there’s no doubt that while the steady state group only improved VO2 max, it did not improve anaerobic capacity. This is absolutely no surprise given the training that was done. Nobody would expect steady state aerobic training to improve anaerobic capacity. Endurance athletes use a variety of training methods and that’s because no single intensity can possibly improve everything important to their performance.

And while the Tabata protocol certainly improved both factors, they only made progress for 3 weeks before plateauing on VO2 max and 4 weeks for anaerobic capacity. Basically Tabata training gave some nice short improvements that tapered off quickly.

Interestingly, the running coach Arthur Lydiard made this observation half a century ago. After months of base training, he found that only 3 weeks of interval work were necessary to sharpen his athletes. More than that was neither necessary nor desirable. The German Track Cycling team tops off months of aerobic training with as little as 10 days of anaerobic training for the 4000m time trial so this isn’t an uncommon pattern.

Other studies using cycling have found similar results: intervals improve certain parameters of athletic performance for about 3 weeks or 6 sessions and then they stop having any further benefit.

This raises an important practical question for all of the “All HIIT all the time” or “HIIT only

” zealots which is this. If HIIT training gives it’s maximal benefits after 3-4 weeks of training, what are people supposed to do the other 48-49 weeks of the year? Should they keep busting their nuts with supra-maximal interval training for no meaningful results? I daresay not.

In that vein, I think it’s worth re-mentioning that the Tabata group did do a single steady state workout per week (admittedly with a half-volume Tabata protocol). It’s worth considering that at least some of the training effect came from this workout? It’s worth noting that I’ve never seen any of the Tabata-zealots mention that the study subjects also did a steady state workout during the week.

The Importance of Doing it on a Bike

I mentioned explicitly above that the Tabata training was done on a bike ergometer and this is actually critically important. Mainly from a safety standpoint. On a stationary bike, when you start to get exhausted and fall apart from fatigue, the worst that happens is that you stop pedalling. You don’t fall off, you don’t get hurt, nothing bad happens.

As part of their bastardized “Tabatas, many are recommending high skill movements. Not only is it not possible to achieve 170% VO2 max in this way, when fatigue invariably sets in and technique suffers bad things often happen. This is not an issue on a stationary bike (or elliptical or rower).

The Tabata Protocol is Very Specific

As well, I want to make a related comment: as you can see above the protocol used was VERY specific. The interval group used 170% of VO2 max for the high intensity bits and the wattage was increased by a specific amount when the workout was completed. Let me put this into real world perspective.

My VO2 max occurs somewhere between 300-330watts on my power bike, I can usually handle that for repeat sets of 3 minutes and maybe 1 all out-set of 5-8 minutes if I’m willing to really suffer. That’s how hard it is, it’s a maximal effort across that time span.

For a proper Tabata workout, 170% of that wattage would be 510 watts (for perspective, Tour De France cyclists may maintain 400 watts for an hour). This is an absolutely grueling workload. I suspect that most reading this, unless they are a trained cyclist, couldn’t turn the pedals at that wattage, that’s how much resistance there is.

If you don’t believe me, find someone with a bike with a powermeter and see how much effort it takes to generate that kind of power output. Now do it for 20 seconds. Now repeat that 8 times with a 10 second break. You might learn something about what a Tabata workout actually is.

My point is that to get the benefits of the Tabata protocol, the workload has to be that supra-maximal for it to be effective. Doing thrusters or KB swings or front squats with 65 lbs fo 20 seconds doesn’t generate nearly the workload that was used during the actual study. Nor will it generate the benefits (which I’d note again stop accruing after a mere 3 weeks). You can call them “Tabatas” all you want but they assuredly aren’t.

That is, just doing something hard for 20 seconds and easy for 10 second and repeating it 8 times is not The Tabata Protocol. And calling it a Tabata doesn’t make it so. If you can’t hit the 170% of max intensity that is seen in the study, it doesn’t qualify.

A Pedantic Note about Vo2 Max

Finally, as I discussed when I talked about the determinants of endurance performance, VO2 max is only one of many components of overall performance, and it’s not even the most important one. Of more relevance here, VO2 max and aerobic endurance are not at all synonymous.

Many people confuse the two because they don’t understand the difference between aerobic power (VO2 max) and aerobic capacity (determined primarily by enzyme activity and mitochondrial density within the muscle).

Other studies have shown clearly that interval work and steady state work generate different results in this regards, intervals improve VO2 max but can actually decrease aerobic enzyme activity (citrate synthase) within skeletal muscle.

The basic point being that even if the Tabata group improved VO2 max and anaerobic capacity to a greater degree than the steady state group, those are not the only parameters of relevance for overall performance. To improve actual endurance means performing actual aerobic work.

Summing Up

First, here’s what I’m not saying. I’m not anti-interval training, I’m not anti-high intensity training. I’m not. I’ve done more HIIT workouts over my athletic career than I care to think about. They are an important part of athletic performance for many sports and research clearly shows they can have important benefits.

I am anti-this stupid-assed idea that the only type of training anyone should ever do is interval training, based on people’s mis-understanding and mis-extrapolation of papers like this.

High-intensity interval training and the Tabata protocol specifically are one tool in the toolbox but anybody proclaiming that intervals can do everything that anyone ever needs to do is cracked. That’s on top of the fact that 99% of people who claim to be doing ‘Tabatas” aren’t doing anything of the sort.

Because 8 sets of 20″ hard/10″ easy is NOT the Tabata protocol and body-weight stuff or the other stuff that is often suggested simply cannot achieve the workload of 170% VO2 max that this study used. It may be challenging and such but the Tabata protocol it ain’t.

Similar Posts:

- Metabolic Adaptations to Short-Term High-Intensity Interval Training

- Steady State vs. HIIT: Explaining The Disconnect

- Steady State vs. Intervals: Summing Up

- Endurance Training Method 4: Interval Training Part 2

- How to Set Exercise Intensity

Great review Lyle!

I can’t even imagine how many buckets had to be on hand when running that study. There must have been a lot of cookie tossing.

Thanks for clearing this up! Very interesting. I once tried something approaching this protocol on a steep hill- 20 sec sprints- but usually couldn’t even make it the full 20 seconds, much less do a repeat after 10 sec rest. That was really hard.

Re endurance exercise not affecting anaerobic capacity, I don’t know what you mean by anaerobic capacity. As intensity increases, more lactate is produced, and if you are trained for it, you can metabolize this increasing lactate more efficiently, as the preferred fuel that it is. Is this what you mean? I’ve read where coaches specifically advise very high mileage (running more than 70 mil/week) with the idea that eventually the slow twitch fibers get fatigued even at moderate paces, and the fast twitch fibers get recruited to shoulder more of the work load. Also, the fast twitch begin to adapt to become more slow twitch-like, with increased mitochondria and capillary supply. In running, it is typical to do easy efforts but also harder efforts like tempo paces and intervals of varying intensities to train the use of lactate. It seems there is a continuum of training intensities, each with its own advantages.

Cynthia: Anaerobic capacity means exactly what I said in the research review, it was tested as a 3 minute maximal effort to see what oxygen deficit could be created.

Basically it’s a measure of the maximum amount of energy that can be generated anaerobically (as estimated by the size of the oxygen deficit that can be created).

That is different than what you are discussing which is the ability to buffer lactate during long efforts at or near the lactate threshold. Anerobic capacity applies to intensities much higher than that.

Lyle

Lyle,

Great stuff, as usual.

Just curious, but as far as cardio “machines” go, would the Versaclimber 108 Sport Model (I believe that is currently their top model) have potential for use performing “authentic” Tabatas, or do you think it would just be too tough for most folks and that you’d end up with some half-cocked version of it?

Has anyone done any measurements of the power outputs people achieve when they do these alternative Tabatas? I’ll use round numbers and take a guess. A 100 kg person weighs about 1000 Newtons and if he raises his center of gravity by .6 meters (2 feet) in one second that would be 600 Joules in one second, or 600 watts. If we only want 500 watts, he’d have to do it about 17 times in the 20 seconds. I’m also not sure if 2 feet (my 0.6 meters) is a good guess for the distance his center of gravity moves.

If my 0.6 meters is right, then someone needs to do around 15-20 bodyweight squats in 20 seconds to do the Tabata protocol.

Thrusters or swings … I actually read about tabata crunches.

Interesting post. I’ve tried Tabatas with weights, body weight exercises, rowing and running. I found them all hard, but there is really something to the rowing and running ones; they were especially hard. Those I did with weightlifting movements felt a little dangerous. Tabatas with body weight movements are difficult and will get the blood pumping but can be too easy to self-regulate

Gonna add a question here:

I like your the information you present; it does a nice job of balancing a lot of the reading I do. So, if I were to purchase one of your books where should I start? Background: I am 30, athletic but with a couple chronic injuries, celiac disease, recently on a low-carb high-fat/protein diet.

I feel the anecdote from Arthur Lydiard and commentary about intervals only being effective for 3 weeks or 6 sessions is misleading. Almost all workout protocols become ineffective at eliciting substantial super compensation after 6 workouts, Poliquin has discussed this before.

I thought your point that tabata needs a supramaximal load was one of the most important. As I understand it, Dr. Tabata modeled his study to investigate a workout by the Japanese speed skating team that was a 20 second all out sprint on skates.

Great article. I have been trying to tell people for a while that true tabata should be at 100% effort, not ‘how much effort I can afford to put in given I have to do 8 lots of 20 seconds.’ People tend to ‘budget’ the effort they put into each interval. Tabata sprints take me a week to recover from and the 8th set tends to see me sprinting at jogging speed.

Thank you Lyle for your excellent discussion on this controversial and often misquoted and misused study.

I have a few comments and concerns about the study itself.

My concern is that the authors of the study used an intensity (70% VO2max) for the endurance training, which is typical of a recreational athlete, against a training regimen which would be more appropriate for a very serious competitive athlete.

Did individuals in either group lose weight during the six weeks and if so how much? In calculating VO2max ml.kg-1 min-1 weight changes will affect the the calculations without any change in delivery of O2.

Once again thank you for your excellent reviews of and explanation of basic exercise physiology.

Ralph

If it takes a professionally trained cyclist to turn the pedals at such high wattage, how did they take the average athletes in the study and have them do such hard pedalling?

Donald: No, they haven’t.

Ryan: Check the store FAQ for book information

Chris: Poliquin is wrong. Endurance athletes will continue to improve the aerobic engine over months and months as long as workload progressively increases. And there are tons of athletes who don’t ‘change it up every 6 weeks’ and keep progressing. And other studies (see Stepto) find that 6 sessions of intervals is all that gives improvements in performance. Which is 3 weeks at 2 sesions/week. Lydiard found the same decades ago.

Ralph: They didn’t track weight loss. Most high level endurance athletes do the bulk of their work at a fairly low intensity and 70% VO2 max is about 80% max HR so it is a reasonable comparison: standard aerobic work to a high intensity protocol.

CL: I gave MY wattage for example. The subjects weren’t nearly as well trained so the wattage demand weren’t as high.

I never intended to suggest a workout with progressive overload will fail to elicit substantial adaptation after 6 workouts.

The issue I have with applying this criticism to intervals is I see no evidence of progressive overload in the literature studying intervals for extended periods. I have not read Stepto’s work, please link me.

Perhaps I implied too much variance with ‘changing it up every 3 weeks/6 workouts’; it’s my impression that athletes who continue to make progress in their routines modify at least one of the loading paramaters (weight, rest, contraction velocity), change the exercise, modify exercise order etc.

I do this with kettlebell snatches once a week for soccer fitness. 8×53 each side, rest briefly, x5. It’s been working beautifully for seven months so far. A brutal few minutes, though.

Lyle perhaps you can clarify something for me with regards to this study.

Since the authors used power ratings, as expressed in watts, to determine the work levels of the individuals in the high intensity intermittent trained group, I would have to assume that they also used power ratings for the moderate intensity group.

They also must have determined the wattage each rider could sustain at VO2 max. Do the authors describe the method they used to calculate this number? Did they do a step test or did they just do a long warm up followed by an all out interval for a set amount of time (2,3 or 4 minutes).

When they state that the endurance trained athletes were working at 70%VO2 max I am assuming that that means they were maintaining a workload measured in watts that was 70% of the VO2 max wattage.

In that case I am not sure that a work load of 70% of the VO2 max wattage would necessarily translate into 80% of an individuals max heart rate.

Finally on this same note what method was used to determine each individuals maximum heart rate? Did they just calculate this or did they actually measure it.

If I could get the full transcript of the original article I would look up the answers myself.

At any rate your input an interpretation is always very informative.

Looking forward to your input.

Ralph

To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering observable, empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning.

So, if I run ‘bodyweight tabatas’ for example, and gather observable, empirical and measurable date to suggest that it works for me, is it not science? I have proven results of over 6 weeks, with steadily increasing numbers, showing my speed, muscular endurance, and my heart all getting gains.

My point is, experiment with your own body and find out what works for you. Whatever works for you is right. I agree with the author’s idea of ‘don’t let anybody tell you one system is the best,’ but I don’t agree with the author’s take on plateauing after 3 weeks, so don’t focus on it. In the study, gains weren’t as much after 3 weeks, but it didn’t stop! They still had gains, just not as much as first 3 weeks, and with ANY program that type of result is going to be produced. With me in particular, I still have gains going into week 7 of tabata intervals 4x per week. I do other workouts as well, but tabatas are a majority and I can cite them as efficient and they work.

They don’t have to directly emulate Tabata’s protocol to be effective and it’s been seen all over the globe right now. Does it have to be a published study to realize how effective it is?

interesting article.what i would like to know is- how would you improve your anerobic capacity for running? if you were say, a 400m runner? does this suggest that there is no point in doing anerobic workouts for running other than the 3 or 4 weeks before a race?!

I think this is a great review of the actual protocol, although some factors are left to opinion. In our research of this protocol, and I am a very big fan of CrossFit, I have never given anyone the impression that this interval cycle was to be taken lightly. Something that seems to be tossed around a little in this review… Any decent coach knows this too, and it should be stated that most of the coaches I’ve run into that use it know what they are doing. It is those who don’t know about it and write articles like, “the best 14 minute workout you’ll ever do”, Or “the 4 minute workout”. The media changes everything because they believe they can empower those who don’t care to actually learn about something. This is another great thing this article does.

We’ve used this for everything from cycling (with fixed loads), body weight training, weight training, and running. In fact, we’ve developed a specific treadmill protocol for it. It came at a cost though. For conditioned runners we can usually get them to 0-1min slower than their pace per mile in a recent (<6 weeks) 5k PR and a 12% grade on the actual treadmill. It is quite the religious experience once the perfect speed is found for the athlete (6-7 rounds achieved, and allowing the athlete to make it to 9 rounds means a speed increase). We’ve done the running on flat road, and hills as well, and it just does not have the same affect. The athlete always slows pace and begins to actually pace the protocol, which I believe was touched on in the article. Fixed load, or fixed speeds with fixed inclines change everything.

There was also a reference to doing the Tabata protocol with other exercises that I believe can be effective if properly done, and as an endurance athlete, and someone who does do a lot of strength and conditioning I’ve seen athletes thrive with it. For instance a 225lb deadlift (weight is used based on ones ability) done with this same protocol, and averaging 9 reps per 20 seconds would allow for 423 watts to be generated. I bet not a single cyclist in the tour would pull that off, nor would they probably care to. But, interestingly enough we have seen in our cyclists, that when their deadlift numbers go up (weight), their speed and climbing ability goes up. Same thing every time…

Another thing that should be touched on is that this was done for speed skaters, not endurance athletes. The endurance athletes I see and work with start off not being able to handle an ounce of this protocol because of being completely over trained (yet, not one of them seems to think they are). It takes months if not years to get them out of this type of mentality, which only allows them to physically change.

Thanks for one of the only real articles on this subject.

Chris: YOu can find Stepto’s work on medline, search for Stepto and intervals. And the Tabata study was clearly progressive, complete the set and you go up 11w. They still stopped improve much at 3 weeks.

Seyton: Read it again.

Ralph: Unfortunately, the methods section was shockingly vague in terms of what they did exactly so I can’t give more detail. they simply stated that they tested VO2 max. No other information was given.

Arturo: And? I didn’t say you could’t do it running or that it wouldn’t work. I said that the study used cycling and people fall apart technically with other modes. The words, they mean things.

Pad: 400m running is in a very weird place that some coaches call the Mystery Zone. At ~45 seconds for elite athletes not purely aerobic and it’s not purely anaerobic. So their training tends to involve more of a mix than either pure sprints (100m) or pure endurance sports. They need good top speed, good lactate buffering, good anaerobic capacity and good aerobic development. As well, there are different ways to compete the 400. Some guys come up with the 200, great top speed and they tack on endurance. Some come down from the 800, great sustainability and they train more top speed. It’s a hard event to train for.

Bmack: The point about speed skaters is a good one which is why I mentioned it. As someone who’s been involved in the sport for going on 5 years, it has demands that no other endurance sport has. Even the distances are highly anaerobic and each lap is skated interval style (you work the corners and relax on the straights). So skating developed a lot of workout that alternat things like 15 second hard/15 seconds easy to mimick how we skate a lap. Other endurance events don’t really work that way.

Great info 🙂

I don’t understand the 170% of VO2Max though – I would’ve thought 100% was the max by definition. How does one know if they’re at 170% of their VO2Max? If 50% of VO2Max is you say 60-65% of max heart rate, what is 170%?

It would be more accurate to state taht they worked at a wattage that was 170% of their Vo2 max wattage. That is, consider someone who hits their VO2 max at a wattage of 300watts on the bike.

Given sufficient encouragement and motivation, they can sustain that for somewhere between 3-8 minutes.

But for short periods, say 20 seconds, they can crank out more than that. So in this specific case, the goal would be 510 watts for the 20 second bouts. So that’s 170% of VO2 max.

For shorter periods, 1-5 seconds they might hit higher than that (track cyclists can hit 1000 watts in their first stroke on the bike but they can’t sustain that for more than a second or two).

Hope that makes sense.

Lyle

Regardless of your sport or activity, or if you just want to get fit your training regime must have VARIETY.

One of the two areas that the Tabata prottocol is said to elicit gains is that of “anaeriobic capacity”. Is it known how that was measured and how does anaerobic capacity show during exercise, ie what does a peson with high anaerobic capacity do better than someone with a low anaerobic capacity?

What abilities would someone with high “Anaerobic Capacity” have, what would they be good at, besides doing the Tabat protocol? I do cyclo-cross racing during th ewinter which involves frequent anaerobic efforts and am wondering if Tabata protocol would help me

John: Anaerobic capacity was measured using something called Maximal Anaerobic oxygen Deficit, basically it’s a measure of how much of an oxygen debt can be generated anaerobically, basically how much energy they can use anaerobically.

In general, folks who are anaerobic dominant can start hard and fast but tend to die quickly b/c they rely too heavily on anaerobic metabolism. You might want to read the long series I’m doing on endurance training methods for more on the topic of actual training.

Lyle,

There are some people who don’t benefit from steady-state aerobic training – for example, (C. Bouchard et al. 1999) put a large sample of sedentary people through a similar 70%VO2max/40min regime and found that around 10% improved their VO2max and endurance not at all even after months of full compliance. Such “low responders” have a genetically limited training adaptation.

Do you think that a Tabata regime might be more or less useful for such individuals? Is there a possibility that interval training might improve fitness where continuous aerobic does not?

I ask because I’m sort of running a personal trial with a sample size of one on this. My VO2max effort on a stationary cycle is around 140 watts (yes, confirmed by labs). Four years of 75%VO2max*40min*5day/wk hasn’t improved this by so much as a single watt, so after learning about the Tabata protocol recently I’ve been trying to replicate it as exactly as possible: ie, a work interval of 240 watts at 100rpm, which works out to failure in the seventh set. Three weeks into this I perceive a modest benefit — I’ve increased workload once to 251 watts to keep failure in set 7 — but now your article makes me wonder if there’s further improvement to be had, or if that three weeks’ gain was the limit.

Bouchard’s work has mainly been on genetics. If someone doesn’t have genetics to adapt to endurance training, I doubt you’ll see any difference with intervals vs. steady state.

I haven’t finished the entire article. When I saw this part , ” You don’t fall off, you don’t get hurt, nothing bad happens. The folks suggesting high skill movements for a ‘Tabata’ workout might want to consider that. Because when form goes bad on cleans near the end of the ‘Tabata’ workout, some really bad things can happen. Things that don’t happen on a stationary bike.” WOW man, you are real good. That’s something I should really watch out for, cause I just started clean not long ago while I have been using HIIT for a while. And I didn’t notice that. Seriously, Thanks a lot man, I might have gotten hurt.

Great site overall and highly clarifying article.

My eyes probably have those black and white spriails in them from reading he crossfit boards discussion on the subject, not to mention every other subject.

It is great that Crossfit motivates a lot of people, but it’s a reach to say it’s effective because it is true. There’s a lot of salesmenship going on there that blurs disintctions.

In particular, I agree that the fact that a 70% VO2max workout was also performed on day 5 is key. Why would Tabata insert unless he believed it would make a difference. The object of the study was perhaps to show that *less* aerobic conditioning is still effective, when supplemented with his intervals. He wasn’t trying to show that it wasn’t needed at all. That would be another test (which others have done). By why a 20:10 interval has become such a dogma? He could have tested 15:15 or 20:20 just as easily. Perhaps others should.

Personally I like intervals because they reduce the monotony. I get a bigger charge from them.

They work for me. But I also like an occasional long run, swim or bike. I never like a long row however. Too grueling! Still, I find that I’m injured more at longer distances than at higher speeds.

So great article, great site. Looking forward to reading more. Thank you !

Great write-up, and I agree that the Tabata craze has gotten ridiculus (I’ve seen Bally’s advertising “Tabata Classes”). I do think it’s worthwhile to not the difference in time and workload between the two groups as the group completing the Tabata protocol put in my less time (and I believe total workload?) than the steady state group but still made real-world progress.

Good writeup on what actual HIIT training is. But the thing is, this study didn’t measure anything like weight loss, body fat composition, or any of these other factors that Tabata training is supposed to help. The study has only measured VO2 capacity and anaerobic capacity. I want to hear about the benefits of doing HIIT for fat loss.

Great Article. Thank you.

Some sports, like wrestling, MMA, Brasilian Jiu Jitsu, other sports i’m sure as well, are fairly short duration, but 100%-you’re-gonna-die-kind of intensity. In the above cases, usually one to three 3-5 minute rounds for the competition.

Question: In training for this type of sport, do you think Tabata training takes on a greater significance?

Thanks.

The graph from Tabata’s study that you quoted clearly shows that while IT group VO2max progress during 2nd 3 weeks was slower than during 1st 3 weeks, it was still better than ET group progress during 2nd 3 weeks, and actually about on par with ET group progress during 1st 3 weeks. Yes, IT group didn’t achieve much in 2nd 3 weeks, but ET group achieved even less.

So leaving the importance of VO2max aside, the study demonstrated that ET training was less effective in improving it than IT training backed by very little ET training (10% by volume of the ET group) – BOTH during the first and second three weeks.

I’d also like to have input on Alexander’s question. I see both training slowing down their improvement in VO2max, which I think is normal, since VO2max eventually tops out. I wish they did continue the study longer and more importantly, showed the power output generated, since for a same VO2max, power could have improved (economy and other factors), albeit at another rate.

Training wise, group 1 must have had a pleasant time and burned more calories, while group 2 must have suffered a lot.

I appreciate this study because it provided thorough information on the pros and cons of Tabata Protocol. I am a ex-triathlete, cross country runner, and outrigger canoe paddler. I know what it’s like to have the long free run days followed by grueling 1500 intervals. I do have a question. I know there is no answer to fitness. There is no one workout that is made for all. My question is, do you believe it’s best to incorporate both forms. What I mean is to have a regimen that involved both endurance and interval training. I have been experimenting on myself by creating a sort of workout that does exactly that. I have been following this regimen for the last three weeks

Here is an average week:

Monday- Circuit Training (Tabata)

Tuesday- Endurance Rowing (1 hour)

Wednesday- Circuit Training (Tabata)

Thursday- Endurance Cycling (1 hour)

Friday- Circuit Training (Tabata)

Saturday- Endurance swimming (1 hour)

Sunday- Rest

I feel this kind of regimen forces an athlete to respond to changes in the workout. One day will be similar to Tabata, while the other will test their endurance capability. It’s more of an adapting regimen. To surprise yourself with a different workout everyday, I would believe it can produce results in both fields. Just a thought. I thank you for your consideration and your attention. I also appreciate any feedback, thoughts, suggestions concerning this idea.

I think you need to read the article again. Then maybe a third time. Because what you heard is not what it said.