Having examined threshold training in Part 3, I want to move up to the next level of training and look at interval training, sometimes called High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT). Now, I’v written about this on this website rather extensively. The context was a little bit different, more addressing the rather asinine either/or between steady state and HIIT that had developed in the fitness industry.

Here I want to focus on HIIT more as an endurance training method although I’ll touch on other topics as well. HIIT actually encompasses several different “Types” of training itself (really, more applications of HIIT for different goals) and is a bit more complex to discuss than the other methods so far. For that reason, I want to focus on some general concepts here and discuss specifics in Interval Training Part 2.

Table of Contents

Defining Interval Training/HIIT

In its most general form, interval training refers to a type of training that alternates period of higher intensity activity with periods of lower intensity training. This contrasts it to what is called steady state training, where a metabolic/physiological steady state is reached. Extensive endurance training, intensive endurance training and even tempo training would all be considered steady state methods.

Strictly speaking, both sweet spot and threshold training, typically done for sets of 10-20 minutes with a 5′ break is a form of interval training in that it alternates shorter periods of higher-intensity work (i.e. right at threshold) with periods of lower-intensity work.

At the same time, those higher-intensity work bouts tend to be steady state in nature. That is, recall that threshold training is done at roughly the athlete’s individual threshold, representing their maximum steady state. So it’s an interval method done at a steady state intensity. There is another type of training called aerobic interval training which is purely aerobic but alternates harder and easier blocks within the aerobic (i.e. steady state range).

Just to further confuse things, I’d note that almost all swimming training is done in an interval fashion and has been for decades. Even training that is done at a steady state intensity (i.e. HR of 130-175/180) is generally done in an interval style. Swimmers simply don’t go swim for 2 hours straight as a cyclist might ride their bike. They may still do tremendous weekly volumes and hours in the pool but it is almost always in a broken interval style. Ice speed skating is at least somewhat similar in that it is effectively impossible to do more than about 20 minute of continuous skating. So workouts tend to be made up of more broken sets with rests in-between them.

To further further confuse things, track and field sprinters often use a type of training called intensive or extensive tempo training which is done in a very interval style. In this type of training the athlete might run at 75% of their maximum speed or less over distances of 100-400m with a relative short rest between runs. The idea is to generate a pseudo-aerobic/conditioning effects without the athletes having to run true distance. But this is not the type of interval training

Putting the Intensity in High-Intensity

But none of those types of training are what I am discussing here. Rather, within the context of this series, all interval training will be considered to be above an athlete’s maximal threshold in terms of intensity. So if their threshold power on the bike is 300 watts (meaning they could do a maximum effort hour at that level), interval training would only be considered to be anything at a higher power output than that. It could be 310 watts or 400 watts. All that matters is that it is higher than the athlete’s steady state threshold.

To delineate this from the more general term interval training, I will call this High-Intensity Interval Training or HIIT with high-intensity referring to an intensity above a steady state level. At this point, anaerobic metabolism will start to predominate and there will be an increase over time of the various waste products that cause fatigue.

By definition this will be an intensity level that cannot be maintained either continuously or for more than a relatively short period of time. How short a period of time depends on the intensity chosen but can range anywhere from 8-10 seconds up to about 8 minutes at which point the athlete will be exhausted and unable to continue.

Some readers might notice that that 8 minute duration overlaps with some of the options I gave for threshold training, which is true. The difference is that, in threshold training, the athlete is choosing to stop at 8 minutes although they could continue at that pace for longer. In the 8 minute HIIT interval, the athlete could not continue at that pace due to the buildup of fatigue and eventual exhaustion.

A Quick Note

Strictly speaking, weight training could be considered a form of HIIT in that it is done for short periods (i.e. 5-12 repetitions) at a non-steady state intensity before a break is taken. However, the adaptations are totally different so it doesn’t really fit within the context of this series.

As well, there is a trend to use non-traditional means such as sandbags or pulling sleds or what have you in a HIIT manner for conditioning. The adaptations here certainly overlap with more traditional HIIT to some degree but are also outside of the context of this series. Rather, I will be focusing on the traditional forms of HIIT as used by endurance athletes. Runners run intervals, cyclists ride intervals, etc.

What is the Purpose of HIIT?

The purpose of performing HIIT is several fold. A primary one is that it trains those other components of performance that the various steady state methods I have described do not sufficiently train. This includes several different components of performance including top speed, anaerobic capacity and power and even VO2 max. HIIT will also heavily recruit and hence train the Type II muscle fibers that go generally unrecruited by the steady state methods, threshold training excluded.

In addition, a primary use of HIIT is to allow an athlete to accumulate a decent volume of training at an intensity that they could not readily do continuously. This will be most easily explained with an example.

Imagine an athlete who can currently run one mile in 4 minutes and 10 seconds at a continuous pace who has a goal of running that same mile in only 4 minutes. Clearly, this cannot be done running a continuous mile. However, the athlete could very likely run 400m in 60 seconds before resting, doing it again, resting again, doing it again, resting again, and doing it one last time. This would allow them to accumulate that same mile of distance at a higher speed.

Quite in fact this is how Roger Bannister, the first man to break the 4 minute mile, trained. As he began his attack on the 4:00 mile, he started by running 10X440 in 66 seconds with a 2 minute rest. Over time, he lowered that to 61 seconds per “quarter”. Having stagnated he took a few days rest and came back to run 10X440m at 59 second per quarter.

At this point, Bannister was now accumulating roughly 2.5 miles of running at a sub 4:00 pace. A pace he could have never achieved running continuously. He would eventually start to stretch the distances out to 880m and 1320m run faster than his goal pace before his final assault on the 4 minute mile.

Each of the various “types” of HIIT allow for this and more to be done, allowing athletes to work at a pace that they could not sustain for extended periods but rather accumulate some amount of volume at that pace. Over time this stimulates adaptation that hopefully allows them to maintain that higher pace for longer and longer periods of time.

Even within a given interval type, athletes will often work at less than their maximal time at that level. So with one type of intervals, an athlete might do one all-out 8 minute effort before exhaustion. But in practice they might do 6 repeats of 3-5′ long, accumulating 18-30′ at that intensity. By keeping the intensity below the maximal duration, they can accumulate far more volume, hopefully stimulating more adaptations.

A Piece of Trivia on HIIT

Interval training was “invented” back in the 1930’s by a German coach. At the time, the focus was less on the hard part of the interval as on the rest. At the time it was thought that HIIT primarily affected heart function and it was the recovery “interval” that was most important to making HIIT work. This isn’t completely correct and it turns out that different “types” of HIIT generate different adaptations.

HIIT Parameters

Compared to the other types of training, HIIT is far more complex. For this reason I can’t really talk about it in quite the same fashion as I did with the other endurance training methods in terms of frequency, intensity or duration. Rather, HIIT workouts can be defined by the following primary variables.

- Duration of the work interval

- Duration of the rest interval

- Number of repetitions (one work interval plus one rest interval) performed

- Number of sets performed

- Rest interval between sets (if more than one is being) done

- Intensity (relative to some metric, be it VO2 max or the lactate threshold)

Duration of Work and Rest Interval

The duration of the work interval is exactly what it sounds like. This is set in seconds or occasionally minutes and will last anywhere from perhaps 5-10 seconds at the shortest up to 8 minutes at the very longest depending on the goal.

The rest interval is the rest time between work intervals. Again this is set in seconds or minutes and can be set in multiple ways. Perhaps the most common is as a ratio of the work interval. So a 1:1 rest:work interval would mean the work and rest duration are the same (i.e. 30″ hard, 30″ rest). A 0.5:1 would mean the rest is one half as long as the work interval (i.e. 60″ hard, 30″ rest). A 2:1 ratio would mean the rest is twice as long as the work interval (i.e. 45″ hard, 90″ easy).

The specific rest:work interval tends to depend on the type of HIIT workout being done. But as a generality the shorter the interval duration, the longer the rest interval and vice versa. This can seem counterintuitive at face value but will make more sense when I explain specific types of interval training approaches.

In some types of HIIT, the rest is passive, meaning that the athlete does nothing in between repetitions. In others it is active meaning that the athlete will continue moving at a low intensity.

Number of Reps, Sets and Rest Between Sets

The number of reps performed is just that, the number of times that a given work interval and rest interval are performed in succession. So 10X30″/30″ would mean working for 30″ hard and 30″ easy and doing it 10 times in a row before resting.

In some workouts, an athlete might do more than one set of HIIT with a longer break in between them. So rather than doing 10X30″/30″ as above, they might do 2 sets of 5X30″/30″ with a 5′ break between the two sets. Breaking HIIT sets up like this is generally used to both increase the total training volume but also to maintain quality during the high-intensity portion of the workout.

Intensity

Finally there is intensity where there are technically two intensities to worry about: the intensity of the work interval and the intensity of the rest interval. Intensity is also where HIIT differs from the other endurance training methods I have described. Specifically, it is difficult if not impossible to use standard methods such as heart rate or lactate levels to set HIIT intensity.

The problem with heart rate has to do with lag. By this I mean that heart rate takes a few minutes to increase to reach a steady state level. Over a 30″ interval, heart rate will only increase slightly and will not give an indication of the true effort (for a maximum 10 second effort, heart rate will be useless). Over multiple intervals, depending on the rest between repetitions, heart rate may increase and eventually level off. But it’s not universal. So heart rate is out.

Lactate is equally problematic since it takes some time to accumulate within the muscle and then be released into the bloodstream. At best it might become useful after multiple repetitions with a short enough rest but it doesn’t tend to be accurate.

For this reason, intensity tends to be set relative to some more objective metric. In the cycling power meter community, it is almost invariably set relative to Functional Threshold Power (FTP). So an athlete might perform a certain type of interval workout at 110% of their FTP to achieve a certain goal. In other sports such as running, it tends to be set relative to pace.

Others simply recommend selecting the highest pace that can be maintained for the duration of the interval. So if the athlete is doing 45 second intervals, they should be done at a pace where only 45 seconds can be done before fatigue sets in. A key here is that the pace should be consistent across the interval. The goal is not to start all out and die at the end in most cases.

This approach to setting intensity is a problem for people new to HIIT since it takes some practice to know how to pace. Most will go out too hard at the start of the interval and find themselves dying towards the end. With some practice, it gets easier by degrees to select an appropriate pace.

The same information above holds for the recovery interval although it’s not as important. During the rest interval, the intensity should be super easy as this is the only way to ensure maximum quality during the work interval.

As I said, in some cases it is passive meaning that the athlete stops moving at all (i.e. a runner would just stand and maybe walk around). For active recovery it should be done at about the lowest intensity possible. A runner doing sprints on the track might walk or slowly jog between intervals. A cyclist would spin in an easy gear.

Putting it Together

You can see from the above that the number of HIIT workouts possible might as well be unlimited. And if you ever try to figure out swim training, you’ll probably see that it is. Swimming, which has an additional variable of stroke) simply takes the prize for the most complex interval patterns of any sport I’ve ever seen.

But for most sports what you will see are workouts written in terms of the number of repeats at a given work interval and rest interval and intensity. If multiple sets are done, a set interval will be indicated.

So even though it’s not technically HIIT, consider the Threshold Training I described in Part 3. That workout would be written as 2X20’/10′ at 100% of functional threshold. The duration of the work bout is 20 minutes which should be done at 100% of threshold power. After the first 20′ interval, a 10′ period of easy spinning is performed before the second (of two) 20′ intervals is done.

Or consider the following workout: 2X5X60″/120″@120% FTP 10′ set rest. Here the athlete would perform 5 repetitions of 60″ at 120% of their FTP with 120″ (2 minutes) of easy spinning in-between each repetition. They would then spin easily for 10 minutes before repeating that set. And yes, that 10 minutes would typically include the built in 2-minute rest of the last interval. That is, they wouldn’t rest 10 more minutes after the 2 minute rest.

Variations by Sport

I should at least mention that while intervals are commonly set in terms of their duration, with that duration selected to achieve a specific physiological effect, this isn’t universal. Some use distance instead.

Using duration per se tends to occur in sports where measuring distances isn’t particularly easy. Sports such as road cycling, distance running, cross country skiing, rowing and probably others just go by time for both the work and rest interval. Distance here really doesn’t matter that much in a physiological sense and it’s easiest to just work for some duration and rest for some duration.

In contrast, sports that involve training or racing on a set distance such as track running, track cycling, swimming or ice-speed skating tend to use distances instead of time per se. This is mainly a convenience thing. If you are a track runner on a 400m running track you have two straights and two curves and it makes sense to start and stop at specific places on the track.

The same holds true for track cycling and ice speed skating. In the latter, straightaway and corner technique are totally different and it matters whether you attempt to start a repeat on the straight or in the corner. So coaches tend to pick distances that will put the athletes where they need to be.

In this case, the athlete is given a target time to complete a given distance. With that distance invariably being chosen to put the athlete at the duration to achieve a physiological goal. So if a track coach wants the athlete to do 60 second intervals, they might give a high level runner 400m repeats and a lower level runner 300m repeats. The athlete would complete that distance and then take some amount of either walking or jogging rest. Here the distance would be chosen to give the rest interval the coach wanted. Running an all out 400m is about 60″ for high level athletes and walking that same 400m is probably twice that.

When I was speed skating we did a workout called lap-on/lap-off. Here we skated 400m at at a lap pace (usually in the mid 30′ range) and then rested one lap. We’d start at the normal starting line, skate until we hit it again and then stand up and just coast around the ice. When we got to the starting line again, we’d do the next lap.

There are other options as in swimming where athletes not only work over fixed distances but solely off the clock. So the athlete will be given a certain distance to be swum in a certain amount of time with the repeats starting at a specific point on the clock. So you might do 100m repeats (about 1 minute) on 1:30. So when the clock hits zero, you start swimming. You hit the wall and when the clock hits the 30″ you go again. And again. And coaches manipulate the distance, goal speed and clock to get the effect they want.

We did this in speed skating as well. So our coach would give us 3X800m on 2 minutes. So first you skate 800m (2 laps) as hard as possible. And the next set starts at the 2 minute mark. If you finished the 800m in one minute, you get one minute rest. If you finished in 1:30 you got 30 seconds rest. Which in a sense made it harder for the slower athlete.

In all of these cases what you see is that coaches have figured out what distances are going to achieve the types of training effect they want. On the ice, 400m is about 30-35 seconds or so at full speed. If the coach wants 20-25 seconds, you skate 250m (one straight, one corner and a half straight). If the coach wants 60 second repeats, you do 2 laps or so.

And it all ends up being about the same at the end of the day with coaches setting up the specific workouts as times or distances to achieve specific goals (usually making the athlete wish they were dead) based on the specifics of the sport.

Frequency of HIIT

Although intensity and duration are applied very differently for HIIT, I can at least talk about frequency of training. For the most part, HIIT is limited to a maximum of 2 workouts per week on average. This is especially true for running due to the impact forces involved. Other endurance sports often can do HIIT more frequently but few would go more than three times per week on average.

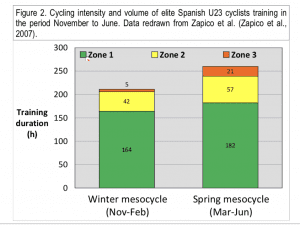

In that vein, it’s important to realize that the total amount of HIIT done by endurance athletes in the modern era is relatively low. At most you might see 10% of a total weekly volume done as HIIT if that. The following image, again from Stephen Seiler’s paper shows the training distribution of elite Spanish cyclists.

Zone 1 represents extensive endurance work, Zone 2 would be intensive endurance up to threshold training and Zone 3 is HIIT. In the winter mesocycle, Zone 2 work makes up roughly 20% of the total training with HIIT making up 2%. In the spring mesocycle, Zone 2 work remains at 20% with HIIT making up a total of 8% of the training.

And this pattern of training, often called polarized training, is common among endurance athletes. Essentially they do an enormous amount of relatively low intensity aerobic work which is then topped off by a small amount of HIIT.

But once again this is mainly for athletes who have a tremendous amount of time to devote to low-intensity training which may not be realistic for the average athlete. In this case, some of the endless extensive endurance work may be replaced by either tempo or sweet spot training to build that aspect of performance. But the total amount of HIIT should not change in absolute terms. Rather, it may make up a relatively larger percentage of the total training due to less total aerobic work being done.

HIIT for Non-Endurance Athletes

To that I’d add that there has been a great deal of interest in HIIT for the general public. Certainly studies show that it can generate similar short-term health and fitness adaptations to longer duration workouts. Given that time limitations is a commonly reported reason for not exercising, this makes HIIT attractive. At the same time, there is often a concern over adherence due to the high-intensity nature of the training. This is not universal and, depending on what is done, some HIIT studies show better adherence and others worse.

My experience is that beginners are unlikely to be willing or able to push themselves hard enough to make HIIT an effective mode of training when they first start. Rather, building some basic fitness over 4-6 weeks before bringing in small amounts of higher intensity work seems to be best. Eventually a mixture of HIIT and traditional aerobic work will probably be ideal. But HIIT should never make up more than 2 workouts per week with the other workouts being more traditional aerobic training.

Finally are the mixed athletes who may have some need to perform HIIT in their training. Generally speaking mixed sports tend to alternate between two intensities: maximum effort and very low intensity. Consider a soccer player for example who might sprint upfield to the ball before slowing down for some period of time to pass or set up a play. MMA and boxing are marked by rapid flurries and then recovery. And their training tends to reflect that as does their general choice of HIIT workouts.

Here again, with so much other training to be done, there is a severe limit on how much HIIT can be added to training while allowing recovery to occur. Much of the HIIT work will likely come through practice of the sport to begin with but any additional HIIT must be added in infrequently and at lower relative volumes.

With that introduction out of the way, let me look at specific HIIT methods.

Read Methods of Endurance Training Part 5: Interval Training Part 2

Similar Posts:

- Endurance Training Method 3: Threshold Training

- Metabolic Adaptations to Short-Term High-Intensity Interval Training

- How to Set Exercise Intensity

- Endurance Training Method 4: Interval Training Part 2

- Endurance Training Method 2: Tempo and Sweet Spot Training

Hi Lyle,

Quick question: what is your opinion (if you have one) on Shaun T’s INSANITY workout? It’s incredibly popular, and based on a concept he calls ‘Max Interval Training’, which means maximum intensity for about five minutes and then a thirty second water break for about twenty minutes total or so. The exercises are a blend of calisthenics and cardio, and the duration of the entire program is 60 days.

Have you heard of this program? Do you have an opinion? I’d be very curious to hear your thoughts, or at the very least follow up with your next post on Friday to learn more as it relates to such exercises.

(And thanks for dumping so much information on your blog–this has definitely become one of my top sites for high quality info.)

@ Extreme Fitness Results

I`d say starting from the name itself you can`t really take that seriously. I dunno if Lyle knows the details – and I don`t – but from your description it basicaly sounds like a full on HIIT-everyday program made of a random mix of different exercises? Like a P90X where you burn out in 60 days rather than 90?

Also, I assume that`s a fat-loss program rather than something designed for athletic development?

What Paolo said.

Also, read the linked articles in this piece, I’ve written about this issue wrt: fat loss etc. extensively.

Beyond that, here’s a suggestion: get on a bike or out to a running track. I want you to warm up and then go 5 minutes at the highest intensity you can maintain for the full duration. By minute 2-3 you should be breathing like a freight train. By minute 5 you’ll want to die. Now wait 30 seconds and try to do it again. When you blow up at the 1-2 minute mark (if you make it that far) I think you’ll understand why a program claiming to have you ‘work hard for 5 minutes’ with a 30 second break and do it 4 times is just stuff to keep the general public entertained. It’s not real interval training because real interval training is murderously hard.

4X5 minutes/30 second rest at anything other than perhaps lactate threshold intensity or below would be uncompletable by most athletes. So, by definition, if that’s what his program entails, it’s pissing around.

true and true.

Lyle

I`m not sure I understand why HR monitoring is useless for intervals.

Joel talks of using HR to determine rest/work periods. That is, work to a certain HR, stop, let it drop to a certain point and then start again.

Do you think that`s not the way to go?

Where in this paragraph do I mention recovery heart rate?

“The problem is lag, it takes heart rate 3-5 minutes (on average) to reach a steady state and with intervals shorter than that, heart rate simply isn’t useful. At best, if someone is doing repeats of a certain interval duration, heart rate will eventually climb up to a steady state.”

That`s what I said, I don` really understand what you`re saying.

Good point. I’ve done some Tabata’s and only been able to go for about two to three minutes, so I completely understand what you’re saying.

I’ve now done a couple of these workouts, and can report back with greater accuracy as to what actually takes place. The reason I’m asking you guys about it here is because I’d love to get some unbiased, professional opinions on the program itself before I decide to continue or not, so thanks for comments in advance if you decide to write them.

I’ll try to be as succinct as I can.

60 days, six days a week, with each Thursday being a yoga-like recovery day and Sundays being your rest day.

Each workout is about 40 minutes long in totum. The first six minutes are a ‘Warm Up’, which consists of three circuits of a challenging set of exercises repeated with greater intensity each time, so that the first set is mid-level, the last is all out, followed by a five minute stretch.

The body of the workout consists of the same format: three circuits of a set of four or five exercises (mixing cardio and calisthenics), with the first being performed at medium intensity, building up to your max at the last. The last five minnutes of the core workout are by far the hardest, and are followed by a five minute cool down stretch.

I don’t think this is a diet program. The nutrition guide helps you work out your basal metabolic rate, and then depending on your weight goals (maintain, gain, lose) they tell you how to adjust that figure. It’s stressed that you see your doctor first, and that you only attempt it if you are already in excellent physical condition.

Could this best be classified as Threshold Training? The gimmicky marketing and verbiage aside, do you consider the core of this workout to be sound, or specious?

Again, thanks in advance for any feedback you can send my way. Much appreciated.

Just think about it this way. What do you expect to have happened to your body after the 60 period? And is this what you really want/need? Also, could you get there training more efficiently? Eg, doing a more structured program 3 days a week rather than a messy one 6 days a week?

Answer these questions and you`ll know if this program is good for you.

Oh, one more thing, all these programs come with a rather hefty pricetag. I watched some of them sometimes and they seemed put together by my 4 year old nephew. So ask yourself whether it`s worth just dishing out the money rather than spend it on learning about training and how to make your own programs.

Good points, Paolo. One of the main reasons I come to sites such as this one is in order to educate myself as to the most effective and efficient ways to train. Unfortunately, as my questions may have revealed, I still have much to learn and thus structured, pre-packaged programs like this one hold appeal.

My goals are quite simple. To boost energy levels, to develop a stronger core, to gain in flexibility and endurance. Hence the appeal of a plyometrics/calisthenics/cardio program such as Insanity; it seems/seemed to promise to deliver what I was after.

Then you may need to rethink your goals. Saying you want to “develop a stronger core” is just too broad.

Let me ask, what do you train for? A “stronger core” means different things to different people. To a boxer it means being able to take body shots repeatedly without going down. To a powerlifter means being able to squat ungodly amounts of weights without caving in. To a fitness freak it may mean being able to do standing ab-wheel rollouts with one arm. Each of these 3 individuals have different requirements of core strenght and each will measure it in a particular way.

Then ask yourself if you really need to achieve these goals. You say you want to increase endurance, but if you where a powerlifter what would you need the endurance for? And if you were a boxer you wouldn`t bother too much with flexibility and so on.

Finally make sure your goals are achievable in the time frame you set for yourself. If your goal was to have the endurance to come 1st at the NY marathon and you only gave yourself 2 months that would be a waste of time. #1 you are very very very unlikely to come 1st at the NY marathon and #2 you definitely won`t get tere by training for just 2 months.

So look at you goals again and ask yourself if you need it, what you need it for, if you can achieve it, how long will it take you and how are you going to measure your progress to know when you actually got there.

And one more thing. When setting up a goal make sure it`s something that you have control over. Eg. wanting to finish a marathon within 3hrs is something you can control entirely while finishing by a certain place also depends on what the other competitors will be doing.

Once you`ve done all this you can start asking specific questions and better research methods to achieve those goals.

Paolo,

Excellent food for thought. I appreciate your time and feedback, and you’ve definitely posed some great questions.

I’ve decided to cut back on this intense cardio training to 3 times/week for the first 3-6 weeks (seems to be the right amount of time for gains according to some of Lyle’s articles), while mixing in some Mark Rippetoe’s Starting Strength resistance training on the alternating days for 3 days a week (consisting mostly of squats, bench, pull ups, and the like). Also going to continue doing yoga twice a week.

The goal is to develop excellent over all health. Having read a number of Lyle’s articles, and thought carefully about your questions, I realize that this is a very vague goal, one that cannot be measured or my progress toward it gauged. Thus, I need to define what ‘over all’ health means, and how I can best and most wisely achieve it.

At the moment, I can only best do that by saying I want to increase my energy, stamina, flexibility and strength. I can only hope to refine those terms/goals as I continue to work out and educate myself, such that eventually I can be precise enough so as to gainfully quantify and measure my progress toward them.

But it’s from generous people like you that I am gaining the right sense as to what sort of questions to ask as I start out, so thank you!

Glad to have helped.

Sounds like you have a plan going.