On Tuesday, in Methods of Endurance Training Part 2: Miles Build Champions, I discussed what is probably the most traditional and common of endurance development methods, to whit “pissing around” at fairly low intensities of perhaps 130-150 hear rate for hours at a time and doing it almost daily.

Table of Contents

The Problem with Miles Build Champions in the Real World

There is no doubt that this method of training “works” and “has worked” for decades in terms of developing the aerobic engine. It has certain advantages and, like all training methods, certain disadvantages. Perhaps the biggest disadvantage for real humans being the enormous time commitment required. With weekly training volumes of 20-40 weeks, that’s still 2.5-6.5 hours per day (depending on the sport) if someone trains 6 days/week.

Realistically only full-time athletes can do that. At most the average citizen racer might get in several shorter workouts during the week and devote more time on the weekends. This is a common pattern with runners wishing to finish a marathon where shorter (30-60 minute) runs are done several times per week with a long run (increasing to perhaps 20 miles) is done on the weekend.

Cyclists, who’s sport doesn’t beat them up as much might do the same shorter rides during the week and then do longer rides of 3-4 (or more hours) on Saturday and Sunday. It’s still nowhere close to the volumes done at the elite level but it is workable. It’s still probably best combined with other methods for optimal results.

But ultimately, due to the way that the Miles Build Champions (again, more generally called extensive endurance training) works, it really requires a staggering amount of volume to be done. If you can’t (or won’t I suppose) put in the time required, the method doesn’t generate a tremendous amount of adaptation or benefit. A few hours per week at this intensity just doesn’t do much.

Tangentially, I suspect that some of the backlash against this method is related to this: unless you can be a full-time and train 20+ hours/week, it simply doesn’t generate much in fitness past the beginner stage. This doesn’t make it useless, just limited. Doing an hour on the bike at a 130-140 or running for 30 minutes a few times per week just doesn’t accomplish much beyond a certain point with a few exceptions.

The Beginner Exception

An exception that I should mention are rank beginners. In all aspects of training, beginners don’t need very much or very intense training to get adaptations. Beginners in the weight room get the same adaptations training at 60% of 1 repetition maximum as at 90%. In general, a single set generates pretty similar gains to 3 sets (this isn’t universally true but isn’t the topic here). And two days per week generates about 80% of the gains as three times per week.

But the point is made: beginners can do a fairly minimal amount of training and get some nice improvements in fitness. In fact, it’s usually better for them to work at lower intensities for a variety of reasons such as adherence, avoiding injury, etc.

In this population, even 20-30 minutes of extensive endurance training three times per week can generate aerobic adaptations. Yes, duration or frequency will eventually need to increase somewhat over the first months of training. But it can be slow and gradual and compared to what elite athletes are doing, it’s nothing. A beginner endurance workout might be a decent warm-up for elite athletes in the same way a beginner weight training workout are the warm-up sets of higher level athlete.

I’d note very tangentially that this is a mistake that people who want to pursue endurance sports make: they try to jump immediately into high volumes of training. The logic, as in the weight room is “If elite athletes do this much, I should do this much.” But they forget or don’t realize that an elite athlete spent a decade or more building up to their current training load. Not only do beginners not need that level of training to start, trying to do it usually does more harm than good.

That latter statement is particularly true of running due to the impact and the injury rate among beginning runners is staggering. Runners are often best served starting with a walk/run program, especially if they have been inactive. It might be weeks before they are running continuously a few times per week. And they must build up more gradually than in any other endurance sport. Cycling, for example, is much more forgiving.

Athletes Who Only Need Moderate Aerobic Development

The second group for whom relatively low to moderate amounts of low intensity aerobic work will be sufficient is those athletes who only need moderate aerobic development in the first place. This is primarily the mixed sports athletes such as most team sports, MMA, boxing, etc. where some aerobic fitness is required but needs to be balanced with many other components. Performing extensive endurance training a few times per week for 30-60 minutes may be more than sufficient. Even the 400m track event, athletes may only do 20-30 minutes of aerobic development per week. It’s simply all they need.

This is especially true since those athletes will invariably be working at much higher intensities in other aspects of their training. Under those circumstances, extensive endurance work may be the only type of “aerobic training” they can really do to begin with without blowing up and overtraining.

Active Recovery/Calorie Burning

Even in that situation where extensive endurance may not be developing fitness to any great degree, there can still be benefits. Active recovery workouts should be done in this range or even lower (i.e. heart rate of 120 or less). Depending on someone’s training status, it can be used to increase calorie expenditure without cutting into recovery. Athletes trying to lean out or simply keep their weight down during their competition often find it to be beneficial. The reality is that dieting physique athletes primarily used this type of training for decades during their contest prep.

Moving on from Miles Build Champions

Which is all a very long introduction to the next methods of endurance training I want to discuss. These apply to situations where an athlete still needs to develop a big aerobic engine but doesn’t have the time to use extensive endurance training as a primary mode.

The idea behind both is that using a higher intensity for a shorter duration of time can have the same “net” training effect. This goes back to the idea of endurance training causes metabolic stress (primarily sensed via AMPk) of some sort. In concept, extensive endurance generate a small amount of metabolic stress and works through the sheer amount that is done.

With both of the next methods, the idea is to cause more metabolic stress per unit time by working at a higher intensity. So that even with a shorter total duration, a similar training stimulus is provided, generating a similar training effect. Essentially both methods trade volume/duration for intensity to try to find an optimal combination of the two to maximize the result.

Intensive Endurance/Tempo Training

The first method I want to describe is usually called intensive endurance training. In the cycling community it’s often called tempo training which should not be confused with the extensive or intensive tempo training done by sprint athletes and which is more of an “interval” style of shorter runs.

As noted above, the idea of intensive endurance is to train at a higher overall intensity such that shorter durations of training generate similar stress and training effects. The training is still definitely aerobic in the sense that metabolism is still aerobic and there is no increase in acidosis over time. So it is still a steady state method.

Duration, Intensity, Frequency

Given that the intensity is higher, the average durations of training tend to be lower although this still depends on the sport. In cycling, a total workout might be 1-2 hours while runners might be 60-90 seconds at most. Presumably other sports are in between those two extremes.

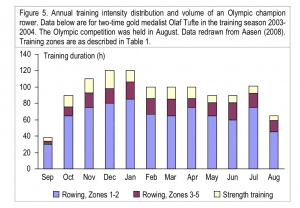

So far as intensity, this tends to be at the higher end of the aerobic range, as high at 80% of maximum with average heart rates being in the 150-170 range or thereabouts. Depending on the sport this might generate lactate levels in the realm of 2.5 mmol/l and possibly a little bit higher. It just depends. I’ll reproduce the graphic from Part 2 showing the elite rower’s training volume and distribution.

Zones 1 and 2 include extensive endurance/Miles Build Champions and Intensive Endurance training with Zone1-2 describing a range of 1-6 hours of training per workout at a heart rate of 55-85% of maximum and a lactate of 0.8-2.5 mmol/l.

Benefits of Tempo Training

In addition to helping build the aerobic engine to a higher level, tempo training/intensive endurance training has the additional benefit of being more time efficient. Per unit time of training, it generates more aerobic adaptations. For the endurance athlete who just doesn’t have the time to devote to extensive endurance, it would provide a better training stimulus. Here a hard hour of training might be similar to 2 hours of easier training.

I’d note that, if there is an “optimal endurance intensity” for developing aerobic fitness, this is probably close to it. In that vein Arthur Lydiard, one of the most famous running coaches) is either “credited” or “blamed” depending on who you’re talking to with the promotion of tons of long slow distance running.

However, the intensity he actually advocated was much closer to the intensive endurance range than anything else. Aerobic running was meant to be challenging, far above the “pissing around” intensity I used to describe the Miles Build Champions method. It’s not quite race pace but you’re working.

And the reason that this is often thrown around as the “optimal” intensity is that, for the time investment, it gives one of the strongest effect. As Andrew Coggan put it in his book Training and Racing with a Power Meter, this type of training offers “the biggest bang for the buck” in terms of time invested to training effect generated.

This is because it comes a higher intensity but with sufficient duration to get a good effect. At too high an intensity, the amount of training that can be done becomes more limited. At low intensity, a ton more volume can be done but also must be done to compensate.

I might note that this has a clear corrollary when training for hypertrophy in that working at a high but not maximum intensity as percentage of maximum and to or near failure gets you the largest amount of volume near your limits as can be done.

Specifically, sets of 5-8 at 80-85% of maximum at perhaps 1-2 reps short of failure optimize the amount of volume done at the best intensity. At a higher intensity, your volume is limited. And at lower intensities, further from failure, you’d have to do a ton more work to make up for it.

Drawbacks of Intensive Endurance Training

The primary drawback of intensive endurance training is that the effort required is quite a bit higher than with extensive endurance training. It’s still a steady state intensity but it’s not necessarily easy. That said, it’s not nearly as gruesome as working at true threshold which might occur at a heart rate of 175-180 heart rate.

For that reason this type of training is not appropriate for beginners to use. Certainly it can be approached after some basic fitness is developed but it tends to be challenging in that population group.

Intensive endurance training is also more difficult to recover from and I’ll address the implication of this tomorrow. Basically, while you can pretty easily do extensive endurance training every day or even multiple times daily, you can’t do this with intensive endurance training.

This also tends to make it inappropriate for those athletes who need some aerobic development but have to balance it against other training adaptations. Intensive endurance training is just too hard to recover from when there’s so much other training to do. Once again, these athletes don’t need the same degree of aerobic development to begin with.

But for non-full time endurance athletes who want to maximize their potential aerobic/endurance adaptations, this would be a better choice of training than extensive endurance. Because whereas only 3-6 hours per week of extensive endurance training is unlikely to generate much aerobic adaptation once athletes hit a certain point, the same amount of intensive endurance definitely will. Once again, a combination of the two with intensive endurance during the week and extensive endurance on the weekends also provides a good combination.

Criticisms of Intensive Endurance Training

As much as intensive endurance training is often held up as the “optimal intensity” for aerobic training, there is also a belief that is is a non-man’s land for endurance athletes and that too much time spent here is detrimental.

What’s going on?

One issue is that while intensive endurance is a time effective way of building the aerobic engine, it leaves other important adaptations untouched. A cyclist who did nothing but this type of training wouldn’t have the endurance for a very long (4+ hour race). Nor would they be prepared for breaks, sprints, climbs, etc.) They’d have a good aerobic engine but lack other components.

Now, for citizen races who only do 1 hour bike races, the endurance issue is a total non-issue. You don’t need the ability to ride for 4-6 hours if you never race that far. The same would hold for a runner who never intends to go past the 5 or 10k range. So far as not being prepared for the other aspects of racing, well, I think this is kind of a strawman argument.

The people advocating intensive endurance as an optimal aerobic intensity have never, to my knowledge, said it’s the only type of training that should be done. An athlete doing nothing but extensive endurance wouldn’t be any more prepared for those types of requirements. But none of them would do only that type of training.

Part of the issue is that while intensive endurance training does a lot to maximize the size of the aerobic engine, it leaves other important adaptations untouched. If someone like a cyclist did nothing but intensive endurance training, they probably wouldn’t be prepared for all types of racing (where breaks, sprints, climbs, etc.) need to be done. They’d have good aerobic endurance but would lack the top end or sprint or climbing skills so often needed in races.

Perhaps the bigger issue is one I mentioned above. Training in the intensive endurance range works really well if you have limited time to train. If you can only get in 3-4 workouts of 1-2 hours apiece, this is the place to train to improve endurance performance (you’ll need some other training too). But I doubt most athletes in this situation are targeting 4+ hours or stage races to begin with. As noted above, if so they can do a longer workout on the weekend.

The problem crops up with athletes can train more frequently or with more volume. Then, intensive endurance intensity becomes a problem because it’s harder to recover from. Athletes who train at an intensive endurance pace daily for long durations never get a chance to fully recover. Overtraining or at least overuse injuries usually follow if it’s done for extended periods.

Essentially, if an athlete can train a lot, most of their aerobic volume should be in the extensive endurance range, perhaps topped off with a little bit of intensive endurance training. Athletes who don’t do that end up outstripping their recovery capacity and get into problems. By corrollary, if an athlete can’t train a lot (by needs or desire), working up in the intensive endurance range works better because they can get similar adaptations with a much lower time investment.

But athletes have to pick one or the other. If they want to train a lot, they can’t train as hard. If they want to train harder, they have to train less. And if they can’t train a lot they have to train harder to compensate.

Sweet Spot Training

Which brings me to the next method of endurance training which has been named Sweet Spot Training. So far as I can tell this terminology was developed by Andrew Coggan who is huge in the cycling power meter community.

To better understand the concept of sweet spot training, I need to describe a concept that is often called the lactate threshold, functional threshold, onset of blood lactate and a whole host of other things. It essentially represents the absolute maximum steady state intensity that can be sustained for an hour or so.

Any lower and you could go longer, any higher and you’d fatigue quickly. It is possible to train right at this intensity and athletes often do. For today I will call this threshold training and I’ll discuss it in detail in the next part of the series. All you need to know for now is what the threshold represents conceptually.

Intensity, Duration, Frequency

In Coggan’s view, the Sweet Spot for training falls somewhere in-between intensive endurance/tempo training and true threshold training. So whereas intensive endurance training might fall in the 150-160 heart rate range of so, true threshold might be in the realm of 175-180 heart rate (this can vary by athlete and sport slightly). So Sweet Spot training would be in the realm of 160-170 heart rate. It’s hard but not maximal. And it’s not so hard that you can’t do it for extended periods or accumulate quite a bit of volume.

As conceptualized by Dr. Coggan, the Sweet Spot represents the true point where you’re generating the maximum amount of metabolic strain (i.e. AMPk activation) per unit time but can maintain it long enough to get in the necessary duration. It’s really just an extension of the intensive endurance concept above. Working at a lower intensity requires longer durations and working at a higher intensity would limit duration severely. As much as anything it’s not quite as miserable as true threshold work.

Most commonly athletes do training at this intensity as broken blocks. So they will do sets of 10-20 minutes with a rest interval of perhaps 1/2 as long. So the workout might be 4-6X10’/5′ rest or 2-3X20’/10′ rest. It is certainly possible to do longer bouts or even go for a straight hour but you have to be willing to work to do it.

Depending on the athlete and the sport, most would do this type of training a maximum of 2-3 times per week. Even three times per week is only for maniacs but might be appropriate for athletes who can only train three times per week. Athletes with time to do other training would usually be better served by combining perhaps two Sweet Spot workouts with one or two other longer workouts at a lower intensity.

Benefits and Drawbacks to Sweet Spot Training

Basically all of the same comments I made above for intensive endurance/tempo training apply to Sweet Spot training but to an even greater degree. For time limited endurance athletes who want to maximize their aerobic engine, Sweet Spot training is a fantastic way to train. With a 10′ warm-up and cool-down, a sweet spot workout might last 1-1.5 hours maximum while generating a massive training effect. It’s painful but extremely effective.

For that reason it’s absolutely not appropriate for beginners who would simply never survive it. Even trained athletes should gradually move into Sweet Spot training if they’ve never done it before. A 5 minute block done every 10-15′ as part of a longer workout is a good way to get used to working at that level. Even using shorter blocks early on, perhaps repeats of 5′ with a 2.5′ break is probably better than trying to go the full 20′ right off the bat.

Those athletes who need some aerobic development as part of their overall performance wouldn’t find it appropriate either. It’s too hard to recover from and would wreck them for other training. It is purely for time strapped endurance athletes who need to maximize their aerobic improvements but don’t have the time for either extensive or intensive endurance on a consistent basis.

In that vein, just as with both extensive and intensive endurance, Sweet Spot training would not prepare an endurance athlete for all aspects of a race. It won’t build much long-duration endurance for example. Nor will it build top end speed or anaerobic capacities to cover breaks or sprints or what have you. But just as with those methods of training, Sweet Spot training would never represent the entire of an endurance athlete’s training. Most athletes can do the longer workouts on the weekend and even one will go a long way here. Top end and interval work would also be needed at some point.

Read Endurance Training Method 3: Threshold Training

Similar Posts:

- Endurance Training Method 3: Threshold Training

- Endurance Training Method 1: Miles Build Champions

- Endurance Training Method 4: Interval Training Part 1

- Surviving Indoor Aerobic Training

- Endurance Training Methods: Putting it Together

Interesting stuff. I’m trying to relate it to what I’ve read in various running books and online sites (mostly stuff written in the 90’s, so maybe the advice has changed, though not that I know of).

It sounds to me like you’re talking about young elite athletes. I say that because the various running books typically give a program something like this–

3 or 4 of your runs should be done at the easy pace, for maybe 3-6 miles

You have one long run of 10 -20 miles, mostly at an easy pace. (20 if you’re training for a marathon, otherwise probably closer to 10)

Then you have one or two days of fast running, which comes in two varieties–

There are tempo runs, which in running books I’ve seen are runs of 20-30 minutes at a speed equal to your 10 mile race pace (roughly the pace you could maintain for 60-90 minutes if you had to). Or you could do tempo intervals, which break it up into 10 minute runs at that pace, done 2 or three times.

And then there are “interval workouts”, where you do runs of one quarter to one mile in length at your VO2 max pace (supposedly your race pace for 2 to 3 miles). You rest for about half the time you run and accumulate a total of 3 or 4 miles of fast running.

This sounds similar to the things you’re saying, I think, except that it sounds like your various workouts are about twice as long in duration as what I’ve read. For instance, your tempo training sounds like the tempo runs I’ve read about, except I’ve always read 20 to 30 minutes was fine. So I’m guessing you’re thinking of elite athletes. Is this right?

Personally, as a nearly 50 year old guy trying to get back into shape, I can’t even do the lower-level workouts I outlined at the level I mentioned. My interval workouts right now only add up to about 2 miles, run at a 7:30 mile per minute pace. I was doing the sort of stuff I described in my early 40’s, but slacked off a bit more recently for various reasons.

great articles, Lyle.

SST training has been the meat and potatoes of my fitness building over the past 2 years as a competitive cyclist.

I highly agree with the warnings about SST and it’s effects on cumulative fatigue; it is HARD, both physically and mentally. Many SST workouts may be written as 1×45 (minutes!) or 2×30′. This is a LONG time to be on the edge of lactate threshold and they take a lot of focus and practice to do right…. but if you’ve only got 75 minutes to get the LT up as high as possible, burn a shitload of calories AND develop the endurance engine, SST is the bees knees. I can burn upwards of 1300 calories in an hour when I’m peaking… this is absurd.

Also I’ll suggest for those just starting SST workouts, aim for shorter durations and shorter interval lengths at first. For many, a steady 20′ interval is completely foreign. Dont go out too fast, but dont slow down either… proper pacing is key.

thanks again, Lyle.

-Leo

The advice you gave on beginners hurting themselves by trying to emulate the elite athletes definitely rings true; a few years back when I started up running I sought to copy a running plan that ended up being too advanced; the first two months felt great, but by the third month I was developing ankle pain, and eventually had to quit. Slow and steady wins the race, sometimes.

Lyle, In the 2nd installment article, you talk about heart rate ranges for runners. I have been doing cardio for many, many years (I teach cardio kickboxing 2-3x per week for the past 6 years) and then have done indoor cardio machines pretty much every other day of the week. Although I am used to running on a treadmill, I recently started running outdoors. In all cardio scenarios, my heart rate is anywhere from 160-200+ (I am 30 yrs old, 158lbs, 5’11” female). Because this is what my heart rate range has been for many years, I never really thought about it. The girl that I run with however, gets a heart rate reading in the mid 130’s when we are running and based on the generic calculation (220-your age x 65%), my target hr should be 123ish. Should I be concerned that my hr is so high? And since I am currently training for a half marathon, is it unhealthy for me to have such a high hr for such a long period of time?

Donald: Reread the third paragraph of the article. The one where I point out that running volume are typically about 1/2 of what you see in cycling or rowing. 20-30′ of running ~= 40-60′ of cycling. This is reflected in Part 4 as well on threshold training. A runner might do a single run at 20′, where a cyclist would typically do 2X20′.

Dani: The 220-age equation is worthless. It was developed decades ago on a small group of sedentary people and can vary by several standard deviations either way. You will find people with true maxes far above predicted and others below it. HR’s if used need to be set on an individual test of some sort, whether it’s a max HR test or field test (e.g. HR at lactate threshold). The estimations just don’ get it done.

Sorry Lyle. I read that, but somehow it didn’t register.

Hi Lyle,

As an armchair athlete, somewhere inbetween beginner and highly trained, my V02Max is about 40mg/l (age 51) I am looking to improve my areobic engine and capacity. The intensive training is of interest – however the closest I can come to an hour workout running is like 6 or 7 nine-minute miles. My HR is about 150 during this. Considering it’s about my best, or max, would you call it intensive or sweetspot? It’s in that range and should support areobic improvement say 1-2x per week ?

Do you believe that using the elliptical machine near max for a similar time would have a similar effect? It is much easier on the ankeles, which is where my problems usually occur.

Or woud you say the bike would be better aerobically?

As you have mentioned cycling intervals after steady state say every 6 weeks do you believe that the next set of intervals would build on whatever gains are acheived in the steady-state, again and again? My objective in this regard would be do run a personal best 5K, currently 22:30, going back several decades!

Thanks so much…

Larry