In Part 2, I discussed intensive endurance/tempo training and Sweet Spot training as conceptualized by Andrew Coggan in the power meter community. There I mentioned the idea of a threshold representing the maximum intensity that can be sustained for some time period (usually defined as one hour). I called it Threshold Training and that is the topic of this part of the series.

Table of Contents

Threshold Training

Early in the study of endurance performance, a great deal of focus was placed on VO2 max, the maximum amount of oxygen that the body could process. And while it was thought to be a primary factor determining performance, that turned out not to be the case. Certainly a high VO2 max was required to be an elite endurance athlete but it was not sufficient.

Later research would turn to a concept that has had many names over the years including lactate threshold, anerobic threshold, individual anaerobic threshold, OBLA, ventilatory threshold and more. In the cycling community its called Functional Threshold Power (FTP).

Years of debate have gone on over what the right name is and what it represents but this is what keeps scientists busy all day. And practically it doesn’t matter in the least what you call it or what it exactly represents physiologically. All that matters is that it conceptually represents the maximum intensity that can be maintained for extended periods. And I’m just going to call it the threshold going forwards. Usually an hour is used to define extended here. It can be defined by heart rate, speed or power output but even that doesn’t matter. The concept does.

In practice, threshold can be determined in a few ways. One way is to look at race performance, especially events lasting an hour. Assuming the athlete knows how to pace, their average speed, pace, heart rate will be indicative of their threshold. An hour time trial can also be done but this is grueling. In practice, most use shorter tests and then use a correction factor. For example, in cycling, the typical approach is to do a 20 minute maximum effort and subtract about 5%. It’s not perfect but it’s close enough.

Along with VO2 max, the speed or power at threshold is one of the biggest predictors of competitive performance. Because what it really represents is the percentage of maximum (i.e. VO2 max) that can be sustained for extended periods. If you have two athletes with an identical VO2 max and one has a threshold of 80% while the other has a threshold of 85%, the second will usually win. In some cases, an athlete with a lower VO2 max but a higher threshold might beat one with a higher VO2 max but lower threshold.

In that vein, Kenyan runners have been found to have a higher average threshold than non-Kenyan runners. When other runners are red-lining, Kenyans have another gear.

Improving the Threshold

As it turns out, one of the “easiest” ways (in terms of the return for the effort put in) to drive up the threshold is to improve the aerobic engine. Simply, if you push up the pace or power that you can do aerobically, the threshold has to go up as well. You can think of this like maximal strength training. Let’s say that you can currently squat 85kgX5 and 100kgX1. If 3 months from now you can squat 100kgX5, then your max is higher.

However, this process takes a longer time since aerobic adaptations take relatively longer to occur. For endurance athletes this is a multi-year process, trying to increase their speed/power output at a submaximal heart rate. Mind you, those adaptations last a lot longer since they are more structural than other “faster” methods.

Most of the debate over the threshold revolves around what the actual mechanism behind it is. It’s not lactate accumulation since lactate actually helps fight fatigue. But the buildup of waste products are probably involved. And what happens when you build the aerobic engine with the other methods, several things happen:

- You can generate more power before starting to generate excessive waste products in the first place.

- You can buffer waste products more effectively when they are generated.

- You recover more effectively between periods of high intensity work (b/c the aerobic engine is more efficient).

With an aerobic engine you not only generate less waste products but you can buffer and clear them more effectively. This is why even intermittent activities often benefit from aerobic development. An MMA athlete with a big aerobic engine recovers more quickly between rounds or even flurries of punches and kicks.

Mitochondria actually have transporters for H+ ions (thought to be involved in fatigue) which mechanistically explains why a big “aerobic” engine can improve anaerobic performance. More and/or more active mitochondria mean a better ability to buffer acidosis. There are other adaptations as well.

In that vein, studies of elite endurance athletes correlate the amount of time spent in low-intensity training as being a good predictor of performance. Anything longer than about 2 minutes is like this even if it seems to violate specificity completely. Certainly some amount of training at or around race pace (or above) has to be done but it’s the low intensity volume that is the key. What is clearly not predictive of performance is the amount of high-intensity work such as threshold work.

But again we have the time issue. Not all endurance athletes have the time to devote to 20+ hours of low intensity work. When they need to drive up their threshold, the most time efficient way to do it is to train at threshold intensity.

This is done by deliberately training at the intensity that generates high levels of waste products along with generating a great deal of metabolic stress. So you’re exposing the body (muscles, etc) to those waste products. This improves the body’s buffering capacity in a variety of ways.

It also generates a great deal of metabolic stress (i.e. AMPk activation) along with having enough volume to still improve aerobic parameters. In that vein, at this intensity Type II muscle fibers will start to be recruited. For endurance athletes, developing aerobic ability in those fibers is important and almost none of the methods discussed so far will train them very effectively.

Intensity, Duration, Frequency

As stated, the intensity for threshold training is basically right at the threshold. If that’s a 6 minute mile for you, that’s your pace. If it’s 300w on the bike, it’s 300 watts. No, you don’t have to hit it exactly and some workouts might wave above and below that to better mimic racing. But the average intensity should be pretty much right at your personal threshold.

Usually this will generate a pretty high heart rate although this varies by person. Most will probably be in the realm of a 175-180 heart rate but it does vary. Some people have lower thresholds than others. This will generate high but steady lactate levels.

In the early days, the threshold was defined as a 4 mmol/L lactate level but this isn’t correct. Individual vary massively in what lactate level they will reach at threshold. Some may be at 4 mmol/l but others will be at 8 mmol/l. What both will have in common is that lactate will go to this level and then stop going up as it would above the threshold. Yet another name for the threshold is the Maximal Lactate Steady State (MLSS) representing this.

The classic way of improving threshold is to train for 20 minutes at threshold. Depending on the sport, you would do 20 minutes right at your threshold and repeat that 2-3 times. Runners usually do 1 and 2 maximum sets and cyclists will do 2-3. I’d assume other athletes do the same. You might see more repeats done at the highest levels of sport but those seem to be fairly common. So a typical workout is a warm-up to 1-2X20′ with 10 minute rest between sets.

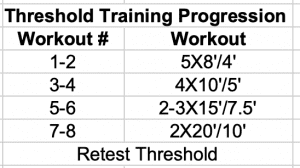

Mind you, the 20 minutes isn’t mandatory, just classic. As with Sweet Spot training it’s possible to do shorter bouts at threshold so long as the total duration and rest interval is the same. An example progression over 8 workouts might be the following.

Or something along those lines.

Cruise Intervals

I should mention another type of threshold training, advocated by running guru Jack Daniels. He uses something called cruise intervals where the athlete might do 4X5′ at threshold with only 1′ of rest in between. The athlete still accumulates the same 20′ at the threshold (without full recovery) but that small break makes it a lot more survivable. Eventually of course they have to buckle down and do the full 20 minutes to prepare for the rigors of racing.

Other Variations

Other variations exist. I mentioned above where the athlete will wave intensity to perhaps 5% above or below the threshold pace throughout the workout. This not only helps with monotony but probably better mimics racing dynamics.

A particularly brutal variation on that is to set the workout right at threshold pace and then go above threshold for a minute or so and then come right back down to threshold. This represents that situation where an athlete might be redlining it, have to launch an above threshold bit to make or cover an attack and then drop right back to threshold pace.

Let me note that the total volume of Threshold Training by most endurance athletes is fairly minimal. At most it might make up 10% of their total training time if that. But that is within the context of them doing an enormous amount of extensive and/or intensive endurance to begin with.

So far as the frequency of training, it is is always very low. On average it might be done once/week (especially for runners) with some athletes doing two sessions per week for short periods of time. Any more than that is too much.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Threshold Training

Essentially all of the benefits and drawbacks I listed for intensive endurance/tempo training and Sweet Spot training hold here to to an even greater degree. The benefits are that it is a rapid way to drive up the threshold along with generating a decent aerobic effect. For time crunched athletes, as part of the other workouts I listed it can play a role.

So far as drawbacks, one is that threshold training is hard. And it hurts. A lot. You are basically redlining at the maximum sustainable intensity you’re capable of and it tends to take a lot of mental concentration to hold that pace in the face of increasing suffering. In many ways, above threshold training (discussed in the next 2 parts) is easier. It hurts more per unit time but you’re done faster.

For that reason it’s totally inappropriate for beginners. It’s also inappropriate for mixed sports athlete who only need basic aerobic training. They’d never recover from it and it wouldn’t serve them any purpose since literally none of their sport is done at that intensity.

Threshold training, like Sweet Spot training is really only for competitive endurance athletes who need to drive up their threshold. But you simply can’t do that much of it. Athletes used to do a lot, back in the 80’s. But nobody does anymore. It might make up 10% of total volume and might be done once per week on average and twice per week at maximum.

Like the other types of training described, threshold training won’t develop everything an endurance athlete needs for endurance performance. It won’t help long duration endurance and it won’t help the top end.

But the first will be built with the other weekly workouts. Whether it’s a 1-2 hour intensive endurance workout or longer extensive endurance workouts, sufficient endurance can be built for the relatively shorter races most will likely do.

And so far as build the top end? That will be done with training done at intensities above the threshold, discussed in the next two parts of this series

Read Endurance Training Method 4: Interval Training Part 1

Similar Posts:

- Endurance Training Method 2: Tempo and Sweet Spot Training

- Endurance Training Method 4: Interval Training Part 1

- What Determines Endurance Performance?

- Endurance Training Method 1: Miles Build Champions

- How to Set Exercise Intensity

Lyle:

Recommendations for the intensity of threshold workouts using heart rate?

PJ Striet

I’m really enjoying this series. However, a basic question: are these methods (threshold in particular) meant for athletes who are already accomplished? Are any of these methods suitable for beginners?

I have the engine of a Honda Civic in the frame of an 18-wheeler.

Your series on this, combined with the fact that I keep gassing out sometime in the middle of my third five-minute round, have convinced me to shed my long-standing bias against steady-state cardio. One way of reading the series, however, is that any intensity range will work if the duration is adjusted inversely. Does specificity really play such a minimal role in endurance?

Selfishly (though I assume many of your readers are in a similar situation), I’d love to know what you recommend for MMA/BJJ fighters, especially for someone who is naturally very muscular (and so burns oxygen faster), doesn’t want to lose the muscle, but does want to last five rounds of five minutes without gassing.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge!

PJ: Well it depends on where YOUR individual threshold is. Generally speaking, it tends to fall somewhere in the 170-180 range or thereabouts for reasonably trained healthy folks. You will see the occasional person who can maintain a higher output for extended periods; in diseased folks, it can be much, much lower. Which is why actually determining threshold level is better than trying to estimate it.

Extreme: I’ll try to get to that a bit on Friday but, in general, you need at least some type of base training (IMO) before jumping into the harder stuff. This is especially true with running due to the pounding. As I noted in Part 3, beginners get adaptations from easy stuff anyway. I see no point in working yourself to death if you can get the same benefits doing less or easier (this is true in the weight room as well, beginners get gains at 60% of max and heavier doesn’t change that. So always start lighter rather than heavier).

Bolidizar: I’m not sure what you’re asking about specificity though but the statement before that is generally true: within some range, you can get essentially the same type of aerobic engine adaptations by either doing tons of low intensity work, moderate amounts of moderate intensity work or smaller amounts of higher intensity volume. Which is sort of the point I’ve been trying to make. And which I’ll try to sum up on Friday.

And I recommend that MMA fighters buy Joel Jamieson’s book from 8weeksout.com since he has infintely more experience with MMA than I do. Contrary to what the internet brain trust prattles on about, used properly, steady state won’t make your muscles fall off (reread Part 1 where I talked a bit about endurance athletes vs. athletes who need endurance). Certainly not if you maintain other work (such as weight training).

Really nice series Lyle. Can` wait for the last one.

I’d reserve descriptions like “gruesome”, “hurts like absolute hell”, etc for VO2max work. Threshold workouts should be quite hard, but still somewhat comfortabe if done in an appropriate amount. At least, that’s the dogma in the running world.

Actually, this was almost a point I made in the article which is a difference between cycling (my primary area of reference) and running.

I’ve primarily done threshold workouts on a bike and the fatigue there tends to be more local (legs) and makes them gruesome.

When I have done threshold workouts running, they are not nearly as difficult since the stress seems to be more local, spread across more muscle groups.

Lyle,

First of all, I’d like to thank you for this series of articles because it’s been a great starting point for me to begin my project of improving my running. With that said, I’d like to ask a question about threshold training… If my threshold runs should be done at that speed which I could maintain for an hour, then surely, after only 20 minutes of running at this speed I should not be that tired? I don’t understand how it can be possible for these runs/bike rides to be so grueling if that pace is actually maintainable for an hour. It jumps to my mind that perhaps my idea of a max effort 1hr run is wrong and that this run should be done with heart rate monitoring and a researcher screaming at you to truly give your maximum effort. In any case, could you give us what you think is your best way to estimate the threshold running speed, perhaps based on a max effort single mile run?

Thanks

Pacing is an issue and the key is that it’s the maximum pace you could maintain for an hour. And as I noted somewhere in this series, cycling for 20 minutes at that pace does tend to feel a bit different than running at that pace since the stress is more local. 20 minutes at that pace running outside of a race situation is still challenging.

As far as determining it, you can’t use efforts that are too short: you would be able to run 1 mile far faster than any pace yo could hold for 20 minutes or an hour and it would grossly overestimate the proper pace. The absolute best way to determine that pace would be in an hour time trial but outside of a race, most wouldn’t be able to do that. So a 20 minute steady state run at the highest possible pace that can be held over the duration would be the next best approach.

I’d highly recommend Jack Daniels Running Formula for more information on running.

“Now, as it turns out, one of the ‘easiest’ ways (in terms of return for the effort put in) to drive up the threshold is to improve the aerobic engine. I would note that this way of improving threshold tends to take time but the effects are also longer lived (since the adaptations are more structural) than other ‘faster’ methods.”

Could you explain the above more detailed? I had a discussion with a friend where he stated that vo2max intervals promote the same mitochondrial growth, etc. When I look at Coggans table of adaptions, it doesn’t look like higher intensity is better for all purposes.

Other sources seem to indicate that there are similair adaptions at higher intensities. For instance one coach suggested vo2max intervals to me for about everything.

I remembered this piece and the words “structural” and llong-lived and faster. So basically now I am wondering if it is true that the mitochondrial adapations are there at higher intensities as well? Are you referring to other adaptions – or is the capillary/mitochondrial adaptions from high-intensity intervals visavi threshold of differing type/quality (with regard to the long term-effect).

Or perhaps I’ve just gotten it all backwards, and if so I am sorry to rehash.