I’ve written a lot about the the physiology of appetite and bodyweight regulation over the years. And while I tend to focus on the physiology of it, it’s important to realize that humans are not just a stomach and a nervous system (as is the case in many animal models). Rather, our appetite and actual food intake can be modified by psychological factors. So today I want to look at a paper that’s been getting some press dealing with the issue of mindset and how it impacts appetite. The paper is:

Table of Contents

Human Appetite Regulation

As I’ve written about previously, human appetite regulation is incredibly complex, involving the complex interplay of hormones, the nervous system, nutrients and the bloodstream and more. More here includes mental state, stress, environmental factors and many others.

The research on this dates back decades and early models focused on the presence of glucose, amino acids or fatty acids in the bloodstream. In the 80’s and 90’s, the focus was on gut hormone such as CCK, PPY and a couple of others.

And things really took off with the discovery of leptin in 1994. Released primarily from fat cells, leptin provided a signal to the brain of not only how much body fat you were carrying but also of how much you were eating. To say I’ve written about leptin endlessly is an understatement.

But the discovery of leptin would lead to the discovery of many more hormones that played a role in human appetite. The one I want to talk about today is ghrelin.

A Primer on Ghrelin

Ghrelin is a hormone released from the stomach. Among other things, ghrelin binds to its receptor in the brain and stimulates growth hormone release.

Trivia for the day: the ghrelin receptor was found before ghrelin. And it was actually the presence of the receptor that stimulated researchers to find out what hormone bound to it.

Importantly to today’s article is this: when ghrelin goes up, it stimulates hunger (it also negatively impacts on calorie partitioning, at least in animal models). Injecting ghrelin directly into the brain reliably increases hunger and ghrelin antagonists (which block the receptor) blunt hunger.

Note that, in a sense, high levels are “bad” (since they drive hunger) and low levels are “good” (since they don’t drive hunger). I’d mention that as leptin falls on a diet, ghrelin levels go up. This is actually a double whammy on appetite.

One of the real oddities of ghrelin is that it seemed to go up before normal meal time. That is, through some mechanism (that I never bothered to go looking for), ghrelin levels would become entrained to when you normally ate. So if you normally eat lunch at 12pm, ghrelin will go up shortly before that to make you hungry.

Side note: maybe this is why dogs always know when it’s time to eat right when the clock hits their normal meal time.

I have a feeling that this explains why changing meal frequency in either direction can be a difficult, at least initially. Ghrelin is going up when you usually eat. So if you try to increase meal frequency and eat sooner, you won’t be hungry. Or if you try to decrease meal frequency, you’ll get hungry at a time you don’t get to eat. Of course, over a fairly short time period, ghrelin seems to entrain to the new meal frequency so it’s not very long lived of an issue.

Most of the early studies on ghrelin looked at how things like food intake, calorie intake and different macronutrients impacted on ghrelin levels. Carbohydrates seemed to lower ghrelin more than fat and protein was unclear (at least as of the last time I looked at this). I’d note again that ghrelin is far from the only relevant hormone.

The total calorie value of the meal seemed to play a determining role and larger calorie intakes dropped ghrelin to a greater degree than smaller calorie intakes. This isn’t really surprising. I even recall one odd study where “sham” feeding of non-caloric fiber or something reduced ghrelin. This was the first indication that something weird was going on.

Was part of the decrease in ghrelin due to people simply thinking they had eaten?

Mindset and Appetite: Part 1

The bottom line is that all of the above background is well and good and interesting and relevant. And it would be the final word on the topic if humans were nothing more than a gut and a nervous system and we just responded in a deterministic way to changes in hormones. Sadly that’s no the case.

Us big brained humans have this thing called self-awareness and sometimes we even use it for our own benefits (as often as not we use it to mentally stress ourselves into oblivion). We can think, reason, justify and rationalize in a way no other animal can. And this impacts on many things including hunger, appetite, food choices, etc.

To whit, humans are the only one who will voluntarily forego eating when they are hungry. It’s called being on a diet and it sucks. No animal would do that. If they are hungry and food is available they will eat. If they are hungry and it’s not, they’ll go find some to eat.

Basically animals tend to eat when hungry and not eat when they are full and that’s where it starts and stops. But for humans that is not the case. Humans will eat out of boredom, due to stress, because they are depressed or because they are at a social event and don’t want to offend the hosts.

Most eat more food on the weekends than during the weekdays and there is a surprisingly strong relationship between the number of people at meal and food intake: more people means people eat more. My point being that you can’t just look at the physiological and ignore the psychological factors. Not that there’s much of a difference when you get right down to it.

A simple example is anorexia where there is a massive desire to eat but the individual chooses consciously not to do so (note: there is probably a lot more going on here). Dieters do the same at a lesser extreme. Individuals trying to gain weight may do the same thing in the opposite direction: forcing food down even when they aren’t hungry.

On and on it goes and you can get into the issue of restrained and unrestrained eaters, rigid and flexible eating attitudes (examined in my Guide to Flexible Dieting), disinhibition and on and on it goes. There are clearly different psychologies when it comes to how people approach eating, food restrictions, overeating, etc.

The point of this being that human hunger, appetite and real-world food intake are all very complicated and sometimes the strangest things can impact on food intake in a way that you might not necessarily predict ahead of time. One of those is related to belief or how people can rationalize or frame certain food choices.

Mindset and Appetite: Part 2

Here is a classic example that will finally segue into the actual paper I want to examine. Back in the 80’s, low-fat diets were the craze. Research had found that carbohydrates couldn’t be converted to fat which is generally true. This got interpreted to mean that you could eat as many carbohydrates as you want and not get fat which is not true.

And what happened was that everybody started gorging on low- or zero-fat foods and nothing good came of it and now people think carbs cause obesity and it’s all just utterly wrong. But I digress.

But a study at the time made an interesting discovery. What it did was gave subjects the same food, I think it was frozen yogurt. One group was told it was low fat and the other was told that it was high fat. Again, same yogurt, they were just told different things. And the low-fat group ended up eating more. Presumably they rationalized that “since it’s low-fat, I can eat more of it.” Which is exactly what was happening in the real world.

There are lots of other examples of this but I’ll only provide one more so I can get to the paper. In nutrition there is something called the “Health halo”. The basic idea is that people will justify eating more of a food that they perceive as healthy. Of course, food companies leverage this all the time, packaging what amounts to candy bars as “health food bars”.

In other contexts, people use the Health halo to justify that eating a “Healthy” food can offset the calories of an “unhealthy food.” In one study, subjects estimated that a burger plus a salad had less calorie than the burger alone. Clearly this is impossible since more food can’t have less calories than less food.

In the real world you see this as the cookie/skim milk or double cheeseburger/diet soda approach to life. Clearly by consuming something “healthy” (or perceived as healthy) with something unhealthy the food cancel each other out.

Which finally brings me to the paper which examined how mindset, specifically the perception of a given food, could impact on both hormone levels, appetite and food intake. Since they were looking at the intake of milkshakes, that led to the amusing paper title.

Mind Over Milkshakes: The Paper

The study recruited 46 participants between the ages of 18-35 who were within a normal to overweight BMI. Of those 46 subjects, 65% werew omen, 56% were white, 12% were African American, 11% were Asian American, 10% were Hispanic/Latino and 11% were listed as “other”.

The subjects were told that the Yale nutritional center, where the study was done was working on two different milkshakes with different nutrient content and that the goal of the study was to see whether or not the shakes “tasted different” to examine the body’s response. Basically they misled the subjects up front. This is common in psychological research since it all hinges on the subjects not really knowing what you’re testing to begin with.

The subjects came to the lab twice and were given the identical milkshake each time. But each time they were presented with a different food label, shown below.

The Indulgent shake was presented as a high-fat, high-calorie shake while the Sensible shake was touted as being low-fat and low-calorie. Again, both were identical nutritionally. This was about what the subjects thought they were consuming.

Each day lasted 2.5 hours divided into two intervals. In the first interval, after a 20 minute rest, blood was drawn at 60 and 90 minutes and the subjects were asked to rate the label of the shake in terms of their hunger ratings (i.e. their hunger before drinking the shake).

In the second interval, the subjects drank the shake within 10 minutes and were asked again to rate hunger along with taste (including smell, enjoyment and healthiness). If you’re wondering how hunger it’s rated it’s done subjectively with the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). This is a little digital doodad where you spin a knob to indicate a response between 0 and 100.

Along with this, measurements of ghrelin were made from the blood draws. Subjects also filled out a questionnaire to determine their degree of dietary restraint. This was just an additional variable to see if restraint scores impacted on the other variables measured.

Mind Over Milkshakes: Results

Unsurprisingly, the subjects rated the Sensible shake as 7 times healthier than the Indulgent shake and restraint had no impact on this. Simply, they firmly believed that the Sensible shake was healthier. How could it not be, right? It said Sensible right on the label. No differences were seen in the ratings of tastiness between shake conditions. This is a bit surprising as sometimes people will report that “diet foods” taste worse than “non-diet foods” even if they are identical. That wasn’t seen here.

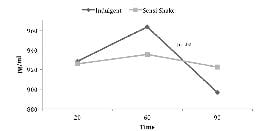

But what about ghrelin levels. This is what most of the Internet reporting on this is focusing. So let’s delve into it a bit. I’ve presented the graph of ghrelin levels below.

.

What you see is that the Indulgent group (solid line) showed a much higher rise in ghrelin prior to consumption along with a much more significant drop. In contrast, the Sensible shake group’s ghrelin response was fairly flat. At least in a purely hormonal sense, this would suggest the following (stated by the researchers):

When drinking the shake in an indulgent mindset, participants’ levels of ghrelin reflected a moderate level of physiological craving followed by a significant level of physiological satiety…when drinking the shake in a sensible mindset, suggesting that, despite consuming the same nutrient contents, they were not physiologically satisfied.

So this is good interesting stuff. The study clearly showed that mindset and preconceived belief impacts on physiology. The subjects who though they were indulging showed a different hormonal response, suggesting differences in both craving and satiety. And those who thought they were being sensible didn’t.

And the interpretation on the Internet of all of this is that the mindset you approach your meals with can impact on your physiological, hunger and satisfaction response. Which this paper certainly suggest. Logically it follows that if you just adjust your mindset, you can sail along in your diet more easily.

Right?

But folks who know me know I don’t bother writing about stuff unless there is more to it. I know this is long but let’s look at the details.

Mind Over Milkshakes: My Comments

So yeah, this is interesting. Mindset impacts on at least a singular marker of physiology, specifically ghrelin levels. And it was the individual’s expectancies of the shake rather than its actual calorie or macronutrient content that drove the response.

And that’s most of what I’ve seen people discussing online about this paper, the hormonal response (one article was titled “It’s All About the Hormones”). Except that it’s not. That’s why I spent so much time on the introduction: clearly human appetite, food intake and bodyweight regulation is far more than just hormones because humans are not physiological automatons.

But there are a couple of important points that got missed, probably by people who didn’t read closely or who didn’t make it past the abstract.

As the researchers state:

Although the effects of such psychologically mediated differences in subsequent consumption or long-term alterations in weight were not measured in this particular study, future research on the impact of this phenomenon on metabolic maintenance is warranted.

This is actually super important. A lot of studies focus purely on short-term responses in terms of appetite, hunger or food intake. And while that’s valuable it may or may not represent the chronic response. Because the body is regulating this and sometimes you see compensation. So maybe you eat a little bit more at one meal for some reason but then eat a little less at another.

Simply, few conclusions can be drawn from this one study in terms of food intake across a day, a week, a month. Don’t misread this, I’m not saying it won’t or can’t have an impact. It might, it might not. Or it might all just balance out over time. The body has at least two distinct regulatory systems, called homeostatic and hedonic and it’s fairly easy for the second to overwhelm the first.

Looking further at their results, the researchers get into a whole speculative discussion about how some of the mindset of dieter’s about their food might be contributing negatively to their overall results. For example, based on data that increased ghrelin tends to drive hunger and lower metabolic rate (at least in animal models), they speculate that:

The relatively flat ghrelin profiles in response to consuming the shake in a sensible mindset may be placing participants in a psychologically challenging state marked by increased appetite and decreased metabolism.

Essentially they are suggesting that approaching eating by trying to be “sensible” maybe making it more difficult for dieters due to increased appetite (rather, less satisfaction) and a decreased metabolism due to ghrelin not dropping as much. Which is kind of a weird interpretation since you could just as easily argue that the big increase in ghrelin before the Indulgent shake would make it easier to overeat.

But it would lead to the idea that if you approached “dieting” with the idea that your food is always indulgent, even when it’s not, your diet might work better. Which there might be some logic to. But I’m not sure this study supports it.

Three Problems

And there are three problems here.

The first is that the idea of altering mindset in how you approach your food is predicated on not knowing the truth. If I prepare a meal of plain chicken breast, broccoli and rice, I’m not convincing myself it’s an indulgent anything. This study gave the subjects a milkshake without them knowing what was in it and told them it was one thing or another. The subjects only had a given mindset because they were misled. And you can’t mislead yourself.

The second is that suggesting a decrease in metabolic rate based on the ghrelin response is a stretch since they didn’t measure it. Rather, they were vaguely extrapolating from animal models and that’s almost always a mistake. I’m not saying there isn’t an impact. I am saying that animals regulated bodyweight and appetite way differently than humans and you can’t make that logic jump.

But it’s the third issue that is really the bigger one. When I described the study I mentioned that appetite and hunger ratings were made with the VAS. Did you notice that I didn’t say anything about it in the results? That’s because I was saving it for now.

Because after all of this blathering about ghrelin, in a single throwaway sentence at the end of the results section, that nobody who stopped at the abstract will ever see, the researchers state what I think is the real finding of the study that everyone is ignoring/missed completely:

For the measure of hunger, these analyses produces no significant main or interaction effects as a function of shake, time or restrained eating.

Translated from science to English this means that there was no significant difference in actual hunger ratings between the shakes, at any time point, or due to the subject being a restrained easter or not. Basically the measured changes in ghrelin levels didn’t amount to any change in real world hunger between the two mindsets. So yeah, mindset impacted on hormonal response. And it had no bearing on real-world hunger at any time point.

I really get the feeling that the researchers were trying to sort of ignore this non-finding of their study. They didn’t even bother to provide the VAS hunger data for the different shakes anywhere in the paper. They went through this whole involved discussion of ghrelin and, as a total afterthought in the results said “Oh yeah, there was no difference in hunger.” and then moved on. It wasn’t even mentioned in the abstract.

So yeah, the physiological hormonal response they measured sure is nifty and worth of more researche. But in real world terms it didn’t amount to anything. Hunger ratings weren’t different at any point in the study. And this is important because people reporting on this study have already extrapolated from the hormonal difference due to mindset and suggesting it will change hunger ratings based on mindset. And only the first is true.

Why Was There No Difference in Hunger?

Given what we know about ghrelin, we might ask why there was no difference in hunger. The best the researchers could do was this:

This study did not find any significant differences with respect to subjective hunger regardless of mindset after participants consumed the milkshake. This result may have been a function of the measuring timing (hunger levels were assessed 10 min prior to ghrelin changes as opposed to simultaneously or subsequently), or the manner in which hunger was measured (visual analog scale).

Basically they are trying to dismiss the non-result by crapping on their own chosen methodology for measurement. No, I’m not saying they wouldn’t have seen a difference in hunger if they had done it differently. But it’s kind of a cop-out. At least they only used the word “may”.

I’d note that the VAS is used extensively to measure hunger and has been for years now. Yeah, it’s subjective but so is hunger. So far as I know, it’s pretty accurate and can discriminate different levels of hunger (if I’m wrong, let me know). So saying that “Maybe a time tested method of measurement sucked because we’re not happy with the results” is just weak. And, of course, there are plenty of other potential reasons that there was no measured change in hunger.

Perhaps the relatively small changes in ghrelin were simply irrelevant to overall hunger drive. Yes, the graph looks pretty impressive but the absolute changes in ghrelin weren’t huge in an absolute sense. And maybe that small of a change just isn’t enough to have an impact.

Maybe given the incredibly complex overlap of systems controlling this, you need to consider the other hormones such as leptin, CCK, GLP-1, PPY and the rest to see how they changed. Perhaps something about the difference in mindset caused one of the satiating hormones to change more and it cancelled out. There are simply too many overlapping systems to look at single hormone in isolation and even attempt to extrapolate to the entire system.

Maybe it was something else going on. We don’t really know until more research is done and speculating is kind of pointless at the end of the day.

Mind Over Milkshakes: Final Thoughts

Here’s what we know from this paper: psychological mindset impacted on the response of a singular hormone that we know is important to hunger drive and satiety. That alone is pretty fascinating to be sure. However, despite that measured change, there was no difference in real-world hunger based on mindset. The hormonal difference just didn’t amount to anything in the real world.

So big picture, who cares?

And that’s really my take-home point here. And yes I took a long time to get there. Everywhere I see people reporting on this paper, they are arguing that you can “think yourself thin” by changing your mindset. Just convince yourself that everything you’re eating is more indulgent than it is so that you can end up with lower ghrelin and be less hungry. Except that’s not what the paper found.

As I mentioned above, I think you could just as easily argue that thinking a meal is indulgent could lead to eating more total food due to the early increase in ghrelin. It didn’t cause that in this study since the subjects were given a single milkshake to drink which is an artificially created situation. Repeat it and let them drink as much as they want and I bet you see a different result entirely with the indulgent group drinking more. Or maybe not. That’s why you do the study.

Mind you, the study didn’t find this either since real-world hunger ratings didn’t differ at any time point for any group. But it would be just as accurate (and just as wrong) interpretation of the physiological response.

So yeah, a fascinating paper: mindset impacts on physiology, perhaps more than we ever realized. Except that despite the physiological difference, nothing real came of it. Hopefully more work on this will determine not only if there is an impact but what the mechanism of it all is.

For now we have this one study which made an interesting observation but ultimately didn’t amount to anything important in the real-world.

Similar Posts:

- Meal Frequency and Energy Balance

- Hormonal Responses to a Fast-Food Meal

- Insulin Sensitivity and Fat Loss

- Insulin Levels and Fat Loss

- Are Low Fat or Low Carb Diets Superior?

Fascinating – it reminded me of the anticipatory insulin response too. It would be interesting to know how long the effect lasts – does the body recompensate ghrelin levels once it realises it’s been conned out of calories? Popped this on our Facebook page – https://www.facebook.com/uncommonknowledge

Your review makes we seriously wonder how many studies cited by enthusiasts are mixed in this way. We know the misuse by guys like Taubes and the HIIT crowd, but how many others abuse research.

Wow, great analysis. Thanks for another fantastic research review.

Excellent review Lyle…thank you.

This reminds me of the hasty interpretations of those studies that show acute hormone responses to various training methodologies…e.g. your GH rises after a triple drop set of one-leg leg extensions > we know GH mediates MPS > do triple drop sets and you’ll be huge.

Only…the real world (muscle hypertrophy measured over a longer time horizon) shows that the causality just wan’t there. Doesn’t stop all the overblown ‘reportage’ however….or the supplement hucksters that jump on board with the newest supp that acutely raises endogenous hormones.

Oh well, lest you feel like you’re a voice in the wilderness, be assured that there are some people that appreciate the rigour of your analysis.

Thanks again.

Long-winded review only to learn there was nothing going on. Thanks for breaking it down, anyway! People really are quick to run with one fact, blow it up, and ignore the actual conclusion. Cheers!

Great article Lyle, thanks.

Very interesting, and great to get it in to context (which I was missing after reasing just the study and another article about it, which I did before I saw your article..)

Well said. The problem with extrapolating changes in ghrelin to changes in appetite is that there are at least ten other mechanisms that signal from the gut to the brain to promote satiation/satiety– nine of which are gastrointestinal peptides like ghrelin and the tenth is stomach distension. The investigators didn’t measure what happened to the other signals, so it’s no surprise that the change in ghrelin didn’t correlate with satiety.

Might have had different results if they had thrown some obese people in there, though it still would need longer studies and more participants to really make any conclusions. interesting stuff, regardless. I didn’t read the paper, and you don’t mention it, but I wonder if restrained vs non-restrained eaters would have different results?

Greetings from Sweden, I love your reviews

I was thinking about other things that influence hunger, such as certain serotonin receptors as far as I know and maybe other things too.

I know that when I tried out 5-HTP my hunger completely subsided for an entire day, while I almost ate nothing. What’s your take on that?

Explanation as to why there was no change in hunger:

“This result may have been a function of the

measurement timing (hunger levels were assessed 10 min prior to

ghrelin changes as opposed to simultaneously or subsequently), or

the manner in which hunger was measured (visual analogue scale).

Additional research endeavoring to understand better how varying

ghrelin levels are related to subjective hunger and subsequent

consumption would be useful.” Crum et al., 2011

Additionally, other studies have shown that when people believe they have eaten a high calorie meal they eat less after that. That there was no change in subjective hunger measures does not mean that there won’t be less food consumed after the fact. (see Polivy et al., 2009 for example).

So no real world change, huh? Think again. Really unscientific review.