Moving on from the topic of protein quality I want to wrap up this guide to dietary protein source by looking at a grab-bag of other factors. This includes the micronutrient content, dietary fat content, and other issues such as availability, the protein content and price.

Outside of a few select groups (that often get a majority of their protein from isolated sources such as protein powders or amino acids), most people get their daily protein from whole food sources and whole foods contain other nutrients. Some of those nutrients may be beneficial, some of them may be detrimental. But all are worth considering.

Table of Contents

Micronutrient Content

The major ‘extra’ nutrients I want to look at in this article are zinc, iron, B12, calcium. In the next part of this article series, I’ll take a look at the issue of dietary fat content, both in terms of good and bad fats. This is simply to keep the length a bit more manageable.

Zinc

Zinc is an essential mineral involved in an amazing number of processes in the body including immune system function, appetite (a lot of early research showed that zinc deficiency did weird things to appetite, zinc has been shown to regulate leptin levels as well) and hormone levels (zinc deficiency can reduce testosterone levels). Since the body doesn’t store zinc, its intake is required on a daily basis.

Zinc is found to varying degrees in most protein foods with oysters containing the most zinc of any food (this probably explains the idea that oysters are an aphrodisiac, given the role of zinc intake on testosterone levels) Red meat, liver and crab meat contain the highest levels after that, chicken is a fairly close second. Eggs and milk are not fantastic sources of zinc although cheese has reasonable amounts.

Grains and cereals, along with beans (often a prime source of protein in vegetarian diets) are relatively poor sources of zinc. As well, compounds in these foods tend to impair zinc absorption in the gut.

Vegetarian diets are often zinc deficient and females (especially female athletes) who have a habit of removing sources of protein such as red meat and chicken also often come up zinc deficient. I’m a huge believer in lean red meat for most people, especially athletes and ensuring adequate zinc intake is one of those reasons.

Iron

Iron is another essential mineral, also involved in a staggering number of processes. Arguably the most well-known role of iron in the body has to do with keeping red blood cells healthy and working.

A lesser known effect of iron has to do with thyroid conversion in the body. Very low levels of iron can cause problems with thyroid production in the liver. Restoring iron levels to normal reliably improves thyroid conversion, can increase metabolic rate and improves thermoregulation.

In the diet there are two types of iron which are called heme-iron and non-heme iron. Heme iron is absorbed roughly 10 times more effectively than non-heme. Like zinc, the best sources of iron (especially heme iron) are meats, especially red meat, liver and organ meats. Chicken is also a good source of iron. Research has found that both red meat and chicken contain a factor that improves non-heme iron absorption by the body.

While many non-meat sources contain reasonable amounts of iron (and many food are iron fortified in the modern world), the iron is typically of the non-heme variety; as well the presence of other compounds in those foods often impairs the iron absorption. I’d note that vitamin C increases iron absorption and consuming some with iron containing foods is one way to improve iron absorption; cooking with a cast-iron skillet also increases the iron content of foods.

Females, due to the loss of menstrual blood each month are at a higher risk for iron deficiency than men (in this vein it’s interesting to note that women are more likely to have thyroid problems, I have to wonder if these two issues aren’t related) and females (especially athletes) along with vegetarians are likely to be iron deficient.

This is especially true for female athletes who have a habit of removing red meat out of their diet. That, along with possibly increased requirements from training, along with slight blood losses each month add up to iron deficiency.

I’d note that too much iron can be as bad as too little, iron acts as a pro-oxidant in the body; men should be very careful about going out of their way to take extra iron and many multivitamins for men have no iron in them for this reason. While women lose some iron each month, excessive iron intake can build up stores in men and cause many problems.

Basically, as with zinc, meat protein, especially red meat is the winner here. This is yet another reason that I think lean red meat (which has also been shown to lower blood pressure and improve blood lipid levels) should be part of any healthy diet. Female athletes especially should probably be consuming lean red meat multiple times per week; supplementation may also be necessary.

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is, as its name suggests, one of the B vitamins. It plays critical roles in the body not the least of which is brain function. While B12 requirements are staggeringly tiny, and the body can actually build up a fairly long store of B12 (in the liver), deficiencies are not unheard of.

B12 is ONLY found in animal source products and vegetarians are often at risk for deficiency for this reason. Individuals who remove animal source proteins from their diet are, as with zinc and iron, at risk for deficiency.

I’d note that there is an oddity with B12 in that a specific factor is required in the stomach for B12 absorption; some people lack this. Even with plenty of B12 in the diet, they don’t absorb it and can end up with deficient.

This can cause something called megoblastic anemia (this is a bit of weirdness to do with red blood cells) along with mental fuzziness. People who lack the absorption factor can’t simply supplement normal B12, they have to get a specific form called Methylcobalamin and this will have to be taken forever to avoid deficiency.

For everyone else, simply ensuring sufficient protein intake from animal source proteins will provide plenty of B12.

Dietary Calcium

Finally is calcium. Known primarily for its effects on bone health, calcium is turning out to play a number of other major roles. Early research found an effect on blood pressure of high dairy intakes and more recently some work has found an impact of calcium (and dairy foods seem to work better in this regards) on fat loss. The mechanism is still unclear although calcium may be affecting fat absorption from the gut, fat oxidation in the body, or some other aspect.

As well, the exact reason that dairy calcium seems to work better is an issue of some question; it may be due to greater absorption of dairy calcium compared to non-dairy calcium or it may have something to do with another factor inherent to dairy products.

The most well-known source of calcium in the human diet is, of course, dairy products. While there is calcium in many vegetable source proteins (vegetarians often claim that broccoli has more calcium than milk), the presence of other compounds in vegetables impairs absorption of the calcium that is present. Meats, grains and nuts are a poor source of dietary calcium.

I’d note, tangentially, that while there has been a long-standing belief that high-protein intakes are bad for bone health but this isn’t supported by current research. As detailed in Protein Controversies, a high protein intake is only a problem when calcium intake is insufficient; a high protein intake along with plenty of calcium actually improves bone health.

As discussed The Protein Book, I am a big believer that low-fat dairy products should be part of any healthy diet. Not only do dairy foods provide an excellent combination of slow and fast proteins, they provide the most available source of dietary calcium and seem to improve body composition and calorie partitioning.

As I’ve said repeatedly, I also think that the weird bodybuilder ideas about removing dairy on a contest prep are not only invalid but actually do more to harm fat loss than anything else.

Of course, not everyone can consume dairy, either due to a true allergy (which is rare) or a lactose intolerance (which is more common). Lactose free dairy products do exist (for example, Lactaid Milk) and there are pills of varying sorts which help with lactose digestion (either by providing the necessary enzyme or helping the gut to start producing more naturally). Failing that, calcium supplements would be indicated for someone who can’t consume dairy (for whatever reason).

Dietary Fat Content

The next topic of interest is that of the dietary fat content of different whole food proteins. Now, this is an area where there is some controversy. Or perhaps debate is the better word.

On one side we have decades of research supporting one interpretation and on the other we have a variety of “fringe” nutritional groups. Said groups having decided that 40 years of nutritional research is flawed and biased, that the current beliefs about fatty acid intake and health are exactly the opposite of the truth, etc, etc.

This debate tends to center around the issue of both total dietary fat intake (quantity) as well as the types of dietary fats being consumed. Much of this revolves around saturated fat intake. On the one hand is a mainstream belief that it is utterly bad and evil. On the other that it is healthful and beneficial. The truth, as always lies in the middle.

Whether or not a given type of fat or even the total fat intake of the diet is good or bad can only be considered within the overall context of the diet and lifestyle. For someone who is active, lean, eating a diet containing plenty of fruits and vegetables and in energy balance, a “high-fat” or “high saturated fat diet” may pose no issue at all. For someone who is inactive, carrying excess bodyfat, not eating much fruit and vegetable matter and in an energy surplus, it may.

Other debates revolve around polyunsaturated intakes. Here the arguments tend to be a little bit more absurd with the “fringe” groups focusing on “excessive” polyunsaturated fat intakes. Said “excessive” intakes being recommended by exactly nobody to begin with.

I don’t intend to cover the entire debate here as I’ve discussed it elsewhere on the site when I examined carbohydrate and fat controversies. I’d refer readers there for more details.

A Primer on Dietary Fat with a bit on Cholesterol

There is often a lot of confusion regarding the issue of dietary fat not the least of which is a common misunderstanding between the issue of dietary cholesterol and dietary fat. Simply, cholesterol and dietary fat are completely distinct chemical compounds. The confusion, mind you, came out of the early research dealing with diet, dietary cholesterol, dietary fat intake, and blood cholesterol levels.

There’s a lot of confusion in this regards but this article isn’t the place to clear it up; at some point in the future, I’ll do a full feature article or series about dietary fats, for now you get the short version.

Dietary cholesterol is only found in products of animal origin and is completely chemically distinct from dietary fat in terms of the molecular structure. Without going into immense detail, the intake of dietary cholesterol really isn’t a big deal outside of a small subsection of folks who appear to be sensitive to it. I won’t say more about it here.

Rather, I’ll focus on dietary fats. Dietary fats are more accurately called triglycerides which refers to the fact that each molecule is made up of a glycerol backbone attached to three fatty acid chains. It’s the fatty acid chains that are of interest as their chemical structure determines not only what the fatty acid is called but what effect it has on the body. There are four major categories of triglyceride which are

Saturated Fats

Saturated fats are found almost exclusively in animal products (with a couple of exceptions), are generally solid at room temperature and are generally blamed (somewhat unfairly) for a lot of health problems, especially increased blood cholesterol levels. And while some saturated fats certainly do raise cholesterol levels, others have no real effect.

Unsaturated Fats

Unsaturated fats are typically liquid at room temperature and tend to be found to some degree in most foods that contain dietary fat; quite in fact, red meat (which is usually thought of as a major source of saturated fat) and eggs both contain a majority of their fat as unsaturated fat. In general, unsaturated fat is fairly neutral metabolically.

Polyunsaturated Fats

Polyunsaturated fats are also liquid at room temperature and found in foods of vegetable origin. Polyunsaturated fats comes in two primary types: omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Many readers are probably more familiar with the omega-3 (or w-3) fatty acids as fish oils.

As a generality, the w-3’s have extremely positive effects on health. An excess of w-6 has been thought to cause some health problems (especially in the context of insufficient w-3) although recent research is starting to question this.

I realize that this last statement is a bit confusing but I don’t have space to explain it here. Since omega-6 fatty acids are found primarily in vegetable source foods, they really aren’t that critically relevant to an article on protein.

Let me note that the fringe angst over polyunsaturated fats tends to revolve around “excessive w-6” intakes. Again said intakes not being recommended by anyone to begin with. Some of the real extremists have an issue with the w-3 fatty acids/fish oils which just demonstrates why you shouldn’t listen to fringe idiots.

Trans-Fatty Acids

Along with high-fructose corn syrup, trans-fatty acids are a favorite whipping boy of people who want simple explanations for the complexities of modern health problems. Trans fatty acids do occur naturally in foods (a point missed by many of the anti-trans fat crusaders) but the majority realistically come from prepackaged man-made foods. Trans-fatty acids are made by bubbling hydrogen through vegetable oils, this produces a fat that is chemically modified but incredibly shelf-stable.

Good for food companies, maybe not so good for human health. A question is just how much trans-fatty acids the average diet will actually contain; of course this will depend on how much of those foods are eaten. Since trans-fatty acids don’t occur in massive amounts in most whole protein foods, I’m not going to mention it further.

Other Fatty Acids

There are also some odd fatty acids that are occasionally encountered. Medium chain triglycerides (MCT, so named because of their medium length) are found naturally occurring in some foods, as is conjugated linoleic acid (CLA).

I’m not aware of any protein source that contains significant MCT (coconut, of all things, is has about 50% of its fat as MCTs) so I won’t talk about it in any more detail. CLA is found in dairy products in small amounts. Most human research on CLA hasn’t been terribly positive although it does amazing things in rats and mice.

The fat loss effects seen in animals rarely show up and some data has found that CLA can cause insulin resistance. The amounts found in most foods are pretty tiny anyhow and I don’t consider it worth worrying about to begin with. I mention it only for completeness.

And with that introduction out of the way, I want to talk about the issue of dietary protein and dietary fat in terms of answering the question what are good sources of protein.

The Dietary Fat Content of Protein Foods

As with the issue of micro-nutrients, the presence or absence of dietary fat (either in terms of the quantity or quality) can impact on the choice of protein source. And this actually turns out to be a place where dietary fat content can vary massively, not only between protein sources but between different sources of the same protein.

As a singular example, while very lean red meat containing no more than 4 grams of dietary fat per 4 oz serving can be found at many stores (we get ours at Wal-Mart), it’s equally possible to find cuts of red meat that contain 20-30 grams of fat in that same 4 oz serving; a 6 to 8 fold difference.

Other protein sources can show similar variance. I’d note that while isolated protein powders are typically extremely low in fat, this isn’t universal; there is actually a whole-egg protein that contains quite a bit of dietary fat, it’s quite creamy tasting.

With that said, I want to look at various whole food protein sources and how their fat intake might impact on whether or not they make a good protein source.

Red Meat

As mentioned, the fat content of red meat can vary massively. And while many have the idea that red meat is primarily a source of saturated fat, a quick look at the USDA database shows this to be false. Perhaps half of the fat content of beef is saturated with most of the rest being unsaturated, with a small amount of polyunsaturated fat usually present. I’d note that grass fed beef can actually have a better fatty acid profile than this.

Chicken/Fowl

Like beef, the fat content of fowl can vary dramatically. Cuts such as the thigh can contain quite a bit of fat while a skinless chicken breast may be essentially fat free. The fatty acid profile is similar to meat meaning that, while there is some saturated fat, the majority of the fat is actually monounsaturated with a small amount of polyunsaturates present.

Pork

Generally speaking, pork products are often high in fat; this can be especially true for prepackaged lunch meats (I’d note that low-fat ham is fairly readily available). A notable exception is pork tenderloin which is about as low-fat as the leanest chicken breast. Tasty, too.

Eggs

Whole eggs contain a moderate amount of fat, typically 5 grams in a single whole egg. I’d note that the white of the egg is essentially fat free and many fat-obsessed athletes have gone the egg white route for this reason.

It’s worth nothing in the context of protein quality that while whole eggs have an extremely high quality rating, egg whites are not so good. It’s also worth noting that, Rocky movies notwithstanding, egg whites appear to be digested terribly. That’s in addition to any potential issues with salmonella poisoning. Cook your eggs before you eat them.

Now, eggs have been in a weird place nutritionally since the early ideas about blood cholesterol, many felt that due to the high cholesterol content (note again that dietary cholesterol has, at most a minimal impact on blood levels anyhow).

If anything the saturated fat content of eggs was the bigger issue. At the same time, whole eggs are an extremely high quality protein and other nutrients in the eggs can be quite beneficial.

As it turns out, a lot of the scare over whole eggs turns out to be false, while a small percentage of people are sensitive even the American Heart Association has removed it’s recommendations to limit egg intake. Clearly individuals trying to limit total fat intake may still wish to limit eggs (or make egg related dishes with a mixture of egg whites and fewer whole eggs).

Like red meat, while a portion of the total fat in eggs is saturated, nearly half is monounsaturated with the remainder being polyunsaturated. I’d note that, recently, high omega-3 eggs have become available, these are made by feeding chickens large amounts of omega-3 fatty acids which changes the fatty acid profile of the egg.

I’d also note that, in the big scheme of things, unless someone is eating a tremendous number of eggs, obtaining a significant amount of w-3 in this fashion tends to be a losing proposition; it would be cheaper to eat normal eggs and take supplemental fish oils.

Fish

Like the other foods listed, the fat content of fish can vary massively. Low fat fish such as tuna is essentially fat free (hence it’s popularity with athletes) while higher fat fish such as mackerel can contain perhaps 12 grams of fat per 3 oz serving.

However, of some interest, and as the names suggest, fatty fish tend to be an excellent source of the healthy omega-3 fish oils. Quite in fact, much of the interest in the omega-3’s came out of the observation that ethnic groups such as the Alaskan Inuit had low levels of heart attacks yet consumed a lot of oily fish. Fatty fish contain quite a bit of monounsaturated fats (about half of the total) with a small amount of saturated fat as well.

However, the reality is that, in my experience at least, most don’t care for the fattier fish and trying to obtain a sufficient daily dose of omega-3 fish oils is probably unrealistic (I realize this comment is biased by my living in the United States where we just don’t eat those kinds of foods). It can be done but I don’t know, practically, how realistic is.

Dairy Foods

Like the other foods discussed, the fat content of dairy foods can vary massively. Non-fat dairy foods are essentially fat-free (perhaps 0.5 grams fat per 8 oz serving) while whole-fat dairy can contain up to 8 grams of fat per 8 oz serving, 1% and 2% dairy products some in between those values. The fatty acid profile of milk is actually predominantly saturated with a small amount of monounsaturated fat and a very small amount of polyunsaturated fat.

As noted above, milk appears to contain a small amount of the fatty acid CLA; while this has shown impressive anti-cancer and fat loss effects in animals, these effects have not been seen in humans. Even if CLA were valuable to humans, it would generally take supplementation to reach significant intake levels.

Beans and Nuts

Although not often thought of as protein foods, beans and nuts can actually provide some protein to the human diet. And while most beans (tofu is a notable exception) are extremely low in fat, nuts can contain quite a bit of fat.

However, a majority of the fat in nuts tends to come from the healthier monounsaturates and polyunsaturates. For example, a 2 oz serving of peanuts contains roughly 12 grams of fat of which nearly half is monounsaturated and most of the rest is polyunsaturated; the saturated fat content is very small.

And while the high-fat content of nuts might predict that they could cause problems with weight gain. However, research suggests that nuts don’t cause the predicted weight gain, probably due to many calories going unabsorbed.

Soy Protein

Although they are technically a bean, soy tends to have enough issue surrounding it to deserve its own specific mention. Most of the issue having to do with soy have to do with the phytoestrogen content. Detailing this is far beyond the scope of the article although I spend quite a bit of time on the topic in The Protein Book.

Unlike most beans, soy can contain some fat, a half block of tofu for example contains just under 7 grams of fat with about half of that coming from polyunsaturated sources, the remainder comes from an even split of saturated and monounsaturated fat.

One consideration regarding soy foods is the phytoestrogen content. These are naturally occurring estrogen like substances that can have physiological effects in the body. However those effects are exceedingly complex and depend on the dose consumed along with who is consuming it. So their effects in a man, pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women can all differ, as can their relative pros or cons. I discuss this in detail in The Women’s Book.

Availability

It should be obvious that whether or not a given protein source is good or not doesn’t matter if someone can’t get it. The ease of availability of a given protein in a given location is clearly an issue but not one I can speak to except in the most general of terms.

What I have access to in the US has no bearing on what someone overseas can or cannot get; in fact I’m quite sure I’ve left out certain whole food protein sources simply due to being located in the US. What someone might have access to in Norway might not be available here and vice versa.

Protein Content

This may seem like an odd category in a series about protein but the simple fact is that many protein containing foods contain more than just protein. For example, as I mentioned above, there is the issue of dietary fat content to consider with protein foods containing anywhere from essentially trace to very large amount. Some protein foods, primarily dairy foods, also contain carbohydrate.

In a practical sense, the actual protein content of a given food relative to it’s total calorie or other macronutrient content can be important. Basically, what I’m talking about here is how much protein a given whole food provides relative to either the serving size or the total caloric content of that food.

If a food provides an enormous amount of protein without providing excessive calories, that food has a high protein content. If it doesn’t, it has a low protein content, at least considered relative t

Obviously, this is relevant from a caloric intake standpoint; a protein food containing a lot of carbohydrate and/or fat will have more calories than one that doesn’t. While studies are repeatedly finding that high-protein diets have many benefits, if trying to raise protein content leads to increased caloric intake, that’s is not automatically a good thing.

Looking at specific diets, many “high-protein” diets are also meant to be low in carbohydrates. This means selecting protein sources that don’t contain too many tag along carbohydrate sources or the protein source itself ruins the diet. Similarly, athletes on high-protein but low-fat diets need to choose protein sources without a lot of tagalong fats in them. You get the idea.

Now, protein sources based on meat (beef, chicken, pork, fish, eggs) contain, at most, trace amounts of carbohydrates. The exception might be if you ate them fresh after a kill (before the muscle glycogen degrades) but I doubt that describes many people reading this. Individuals trying to raise protein while limiting carbohydrates tend to focus on such foods for that reason.

Protein Content in Foods

In general, meat protein will contain about 7 grams of protein per ounce. So a 3 oz piece of meat (about the size of a deck of cards) will generally have about 21-24 grams of dietary protein. The protein content of other foods depends on the food.

Dairy products generally always contain some carbohydrates although the amounts can vary. A typical 8 oz. (236ml) serving of dairy will typically contain about 12 grams of carbohydrates with fat content varying from zero to about 8 grams of fat for whole milk. Cheese is an exception and is typically much lower in carbohydrate containing only small amounts with fat content varying similarly to milk.

Beans and nuts, for their caloric content, tend to be lower in terms of protein content due to the presence of tag-along carbs or fats; it’s also nearly impossible to find such foods that don’t have the other macro-nutrients.

Beans generally contain a good bit of carbohydrate (along with a chunk of fiber), nuts contain a good bit of dietary fat. That is to say, while many animal based foods can provide essentially pure protein (with no carbs or fats), vegetable source proteins can rarely if ever do this.

Vegetarians or individuals who obtain a lot of protein from vegetable sources who are trying to increase their protein intake via these foods invariably end up getting a lot of “extra” calories from the other macros. This makes following high-protein/low-carb diets with such foods nearly impossible without using a lot of low-carb protein powders.

Typically, protein powders provide nearly pure protein with only trace carbs. And very few contain more than a trace amount of fat (whole egg protein powder is an exception). While I generally prefer that diets be based around whole foods (for a variety of reasons), protein powders can provide a very concentrated source of protein for individuals running into problems with other whole food protein sources.

Cost

An issue not often appreciated in answering the question of what is a good source of protein is the cost. Now, unfortunately, this is an issue that tends to be nearly impossible for me to address in any useful way because food costs vary massively.

What I’m paying in the United States will vary greatly from town to town and I have absolutely no feel or perspective on what someone overseas will pay. Issues of availability, etc. will affect local food prices and I can’t cover this except in a very general sense.

What is often useful is to sit down and calculate out the effective cost per gram of protein for a given whole food protein source. Basically, you add up the total protein and divide that by the cost of that food to determine how much you’re paying per gram of protein.

For example, let’s say you can buy an average can of tuna fish (which typically has about 32 grams of protein) for 50 cents. And let’s say you can buy a cup of yogurt (8 grams of protein) for the same 50 cents. Finally, let’s say we can buy a pound of meat (which will contain about 120 grams of protein) for $4.50 (450 cents) per pound. We can compare each:

- Tuna: 50 cents / 32 grams of protein = 1.8 cents per gram of protein.

- Yogurt: 50 cents / 8 grams of protein = 6.25 cents per gram of protein.

- Red meat: 450 cents / 120 grams of protein = 3.75 cents per gram of protein.

Obviously the tuna fish is the cheapest, the red meat is second and the yogurt is the least cost-effective. So from the perspective of protein content only, the tuna fish is the most cost effective. But that must be weighed against all of the other issues I’ve discussed such as micronutrient intake, digestibility or speed of digestion, etc.

MAlthough the yogurt is more expensive, it might still be a better choice for someone who wanted a casein/whey mix along with the dairy calcium. And the red meat would be superior in terms of it’s zinc and iron content.

At least in the United States and possibly elsewhere in the world, protein powders are often less expensive per gram of protein than whole foods. This is on top of being, most of the time at least, nearly pure protein. This has to be weighed against the lack of other nutrients, etc. I think you get the idea.

For anyone reading this, you will have to do your own set of calculations for the foods in your region of the world. Simply determine the cost of a serving of that food and find the total amount of protein and you can calculate out the cost per gram of protein to compare.

Summarizing Dietary Protein Sources

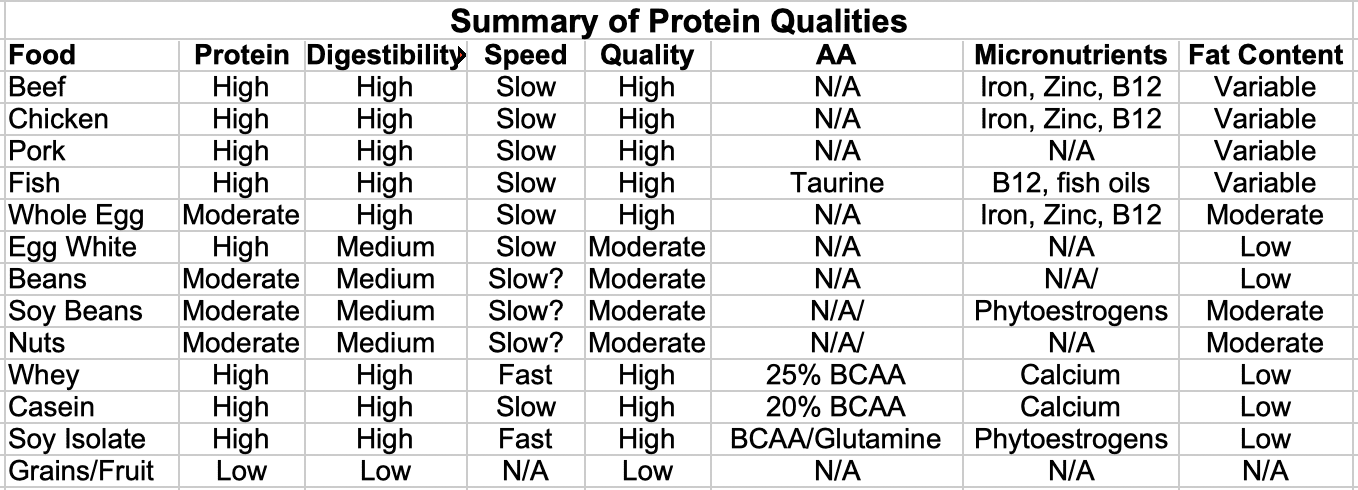

And with all of that out of the way, I want to try to summarize everything I talked about in the previous parts of this guide. I’ll list each food, the protein content, digestibility, speed, quality, etc. Clearly I can’t address availability or cost since they vary too much by region and country.

Let me make a few comments about the above chart.

N/A simply means that there is nothing particularly noteworthy about a given food in a given category. For example, most protein foods tend to be sufficient to meet basic human amino acid requirements. However, casein and whey are both unique in their high BCAA content. Some sources of soy isolates also contain significant amounts of BCAA and glutamine.

I didn’t talk about the phytoestrogen issue regarding soy protein since the topic is too complex. I’ll only say now that the issue of phytoestrogen content is more complex than saying that they are “good” or “bad”. Again I’d refer readers to The Women’s Book.

And that wraps up a rather complete look at dietary protein sources. Hopefully it has provided readers with the information they need to make more informed sources in their protein choices.

Similar Posts:

- The Mercury Content of Fish

- A Complete Guide to Dietary Protein

- Examining Some Dietary Protein Controversies

- A Look at Common Contest Dieting Practices Part 1

- Dietary Protein Sources – Protein Quality Part 1

Aren’t there some recommendations against mixing iron, zinc, calcium all in the same meal? Assuming that one usually supplements w/ zinc before bedtime, what are the best times to take calcium or iron during the daytime so that they do not hinder absorption of other minerals/nutrients?

There has been work in this regards, however typically truly massive doses are examined and the relevance of this to normal meals is questionable. For example, the data on calcium and zinc interactions used stuff like 2-3 grams of calcium. So it tends to be something I don’t think most need worry about terribly.

Lyle

I think vitamin K2 is the critcal element for effective calcium utilization. It’s fat soluble, from animal products. Maybe whole milk is better.

Calcium absorption is very complex, I looked into this in insane detail many years ago and it’s the combination of protein, sodium, potassium, some sugars and a few other things that makes dairy calcium so bioavailable. It’s certainly not just K2

Lyle

Great job in breaking down each major micronutrient – This helps see the picture more clearly on how to include each of these in order to maintain a health diet –

Lyle

I was learining about the sarcoplasmic reticulum in class and how it stores calcium then releases it during a muscle contraction to move the troponin. (I think thats what happens) So if someone had a calcium deficiency would they have a hard time contracting their muscles? Because I dont really hear anything about bodybuilders taking calcium supplements to build muscle.

Scott

The body is usually pretty good at maintaining calcium levels in certain tissues, although deficiencies tend to mean that it gets pulled out of others. I imagine it would take a rather massive calcium deficiency to cause this kind of problem.

Lyle

Regarding Vitamin B12 – you find it in quite large quanitites in yeast extract (marketed as Marmite in the UK) – this would be suitable for vegetarians, although as the advert says “you either love it or you hate it” because of its extremely sour taste. I often include it in soups, stews and sauces to provide this vitamin (although as a non-vegetarian I’m sure I get enough from meat).

I’d argue (looking at the research) that menstrual losses are relatively small.

Therefore, most iron anemia in young women is dietary. In female athletes, it would be both exercise-induced loses and diet.

Re calcium, exercise sweat losses run about a gram/day. Remember the RDA/DRI are age and gender based averages. They are not normed on athletes. See Lappe.

https://www.scribd.com/doc/35561337/HealthPerformMilWomenCBT1995

https://www.scribd.com/doc/35560621/Calcium-Vitamin-D-and-Stress-Fracture

https://www.scribd.com/doc/35597577/McClung-AJCN-09

https://www.scribd.com/doc/35597624/McClung-J-Am-Coll-Nutr-2006

https://www.scribd.com/doc/36060762/Beef-Exercise

https://www.scribd.com/doc/36060836/Iron-Status-Exercising-Women-1991

https://www.scribd.com/doc/36060900/GIT-Blood-Loss

Probably why I wrote this

“Females, due to the loss of menstrual blood each month are at a higher risk for iron deficiency than men (in this vein it’s interesting to note that women are more likely to have thyroid problems, I have to wonder if these two issues aren’t related) and females (especially athletes) along with vegetarians are likely to be iron deficient. This is especially true for female athletes who have a habit of removing red meat out of their diet. That, along with possibly increased requirements from training, along with slight blood losses each month add up to iron deficiency.”

Even if you seemed to have missed everything after the first sentence.