I think it was last year some time that Time magazine ran an article to the effect of “Exercise will make you fit but it won’t make you thin.” I remember someone asking me about this (it might have been my mom) and I wasn’t really sure what the issue was. I had written back in my first book The Ketogenic Diet about some of the realities of exercise weight and fat loss. Most of my other books have at least dealt with the issue to some degree.

I suppose the issue isn’t really one of the realities of exercise and fat/weight loss but rather how the message was misinterpreted. Many have held up exercise as some sort of panacea for all things, health, fitness and of course what everyone is really interested in: losing weight/fat and I suspect the message got a bit garbled as it so often does: people figured that they could do a bit of easy exercise and the pounds would just melt right off.

The realities, unfortunately, are often quite a bit different and I want to look at the possible ways that exercise might impact on one’s overall body recomposition goals.

You’ll notice that I used the word ways plural in that sentence. While most focus on the direct role of exercise on fat loss (via direct calorie and/or fat burning) it turns out that there are more ways than just that for exercise to impact on things.

For the most part, I’m going to sort of cluster all exercise in one big grouping for the sake of simplicity. Clearly resistance training and aerobic training aren’t the same and have differential effects; when needed I’ll make distinctions between them.

It’s important to realize that most research on exercise and fat loss have used obese individuals (researchers by and large not being interested in lean folks trying to get leaner) and that has potentially other impacts on a lot of this. Again, as needed, I’ll make note of this.

Today, since it will take the most verbiage, I’m only going to look at the primary way that exercise can (or can not) impact on body recomposition goals and that is in terms of its impact on total weight loss; that is the quantity of weight lost. I’ll note ahead of time that I am going to confusingly jump back and forth between fat and weight although they are not the same thing. This will make more sense in Part 2 when I attempt to cover all of the other ways that exercise may potentially impact on things.

Table of Contents

Quantity of Weight Loss

Most commonly, exercise is held up as a way of either directly causing weight/fat loss or for increasing the amount of weight/fat lost when added to a diet with the focus primarily on the direct effects of exercise on calorie/fat burning either during the exercise bout or afterwards.

As noted above since it will take the longest, that’s the only issue I’m going to look at today. Basically, I’m going to give a reality check on the impact of realistic amounts of exercise in terms of its impact on body weight/body fat. It’s not a reality many are happy with.

In previous articles as well as in my books, most recently in the Training the Obese Beginner series, I’ve made the comment that, generally speaking, the only people who can burn a tremendous number of calories during exercise are trained athletes; and they aren’t the ones that usually need it. That statement appears to have confused some people but the point I was trying to make is that the number of calories that can be burned with realistic amounts of exercise in beginners is usually fairly low.

Calorie Burn During Exercise

In my first book The Ketogenic Diet, I cited some paper or another indicating that most untrained folks can burn perhaps 5-10 cal/minute in exercise if you’re talking about sustainable intensities; this might hit 15 cal/minute but that would be for high intensity interval-type training.

However, the duration of that activity tends to be exceedingly limited and the total average calorie burn for the activity will be lower due to the rest intervals. As well, this isn’t an intensity of training that can be done frequently. Even achieving 10 cal/minute would be fairly challenging for an relatively untrained/low-trained individual.

Of course, as training status goes up, folks can burn proportionally more calories. A moderately trained individual might be able to burn 10 cal/minute fairly easily and hit 15 cal/minute for extended periods if they are willing to work a bit. 20 cal/minute might be achievable for short periods but, again, the total burned during activity would be balanced out by the low intensity nature of the rest intervals.

When I have compared interval sessions of varying types to steady state training with a Powermeter, the total caloric expenditure is usually about identical because of how the rest intervals affect the average intensity. The steady state sessions are far easier to complete and can be done more frequently as well.

A very highly trained athlete might be able to burn 15 cal/minute as a matter of course, 20 cal/minute if they are willing to work and hit even higher values for high intensity training. Certainly these athletes sometimes need to drop fat (usually to improve power to weight ratio) and they have the advantage of being able to burn a tremendous number of calories with even low intensity activity.

Simply tacking on an “easy” 30-45 minutes to their normal training can burn a pretty large number of calories making fat loss relatively easy without much change in diet. But that last group is not who we are realistically talking about here.

I’d note that the above values are for cardiovascular activities. People always ask about calorie burn during weight training and it’s harder to pin down values. It also depends staggeringly on the type of activities done (e.g. whole body vs. isolation exercises), rest intervals, rep ranges, etc. Clearly repetition clean and jerk will burn a lot more calories than barbell curls.

On average, studies have found a calorie burn of 7-9 cal/minute seems to be about right (again with huge variability) but that only holds for the actual work time and a lot of time in the weight room is usually spent resting. When we have tracked calorie burn for various types of weight training (ranging from Olympic lifting to isolation machine work) with various technologies, a calorie burn of 300-400 cal/hour is about the average.

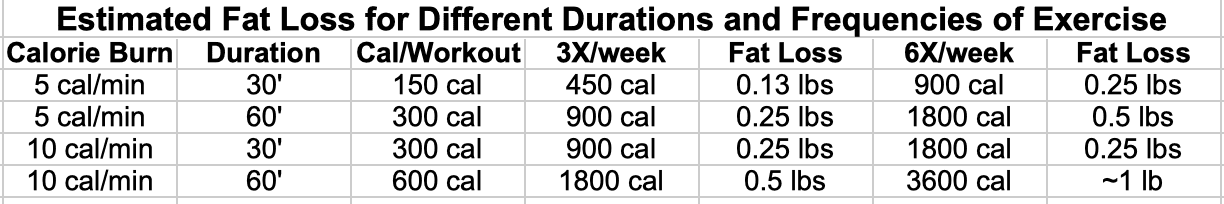

So with the above values in hand, let’s look at realistically what we might expect in terms of weight loss using the values for a typical untrained/low fitness level individual assuming a calorie burn of 5-10 cal/minute and various durations and frequencies. I’m going to compare 30 vs. 60 minutes and 3 vs. 6 days/week to estimate total caloric expenditure.

And here’s where the confusing bit comes in, to put in this in real world terms I’m going to move from weight loss to fat loss with the assumed value of a 3500 calorie deficit to lose one pound of fat; of course this assumes that 100% fat is being lost which is not always a safe assumption. I’d note that total weight loss will be higher if a larger proportion of muscle is lost.

I want to note up front that there is a HUGE assumption built into the following calculations: that nothing else is changing. Not diet, not activity at other times during the day (some studies find that people compensate for exercise based energy expenditure by moving less later in the day), nothing.

The only change we’re making here is by adding exercise to an otherwise static situation. For reasons far beyond the scope of what I want to talk about right now, this is not a good assumption. It simply makes the math easier.

Frankly, the results are pretty dismal. At common recommended frequencies and durations of activity, the weekly fat loss approaches irrelevant. A brisk 30 minute walk three times per week predicts just over 1/10th of one pound fat loss. Double that and you get one quarter pound fat loss per week. One pound a month. To achieve even one pound fat loss per week until you reach 6 days/week of an hour of fairly challenging exercise every day.

The reality is that for all but the highest levels of activity, a complete overhaul of the diet will be necessary.

The Above are Probably Overestimates

It’s also worth mentioning that the above caloric expenditure is actually somewhat of an overestimation since it includes the calories that would be burned by simply sitting around doing nothing. That is, if you did nothing during that hour, you’d burn perhaps 60-100 calories/hour or so depending on that activity. The above values include that resting expenditure so the actual impact on energy expenditure above and beyond normal are going to be slightly lower.

But it’s fairly easy based on the above values (which again represent a massive number of assumptions in the first place) to see how many people have concluded that exercise is worthless for fat loss. And certainly a majority of studies (including most of the big meta-analyses) have reached that conclusion: compared to dieting alone, exercise tends to add very little to the quantity of weight lost. Even added to a diet, exercise tends to impact on the total weight loss marginally at most; the diet is doing most of the work in terms of the actual quantity of weight lost (here I’m switching back to talking just about weight).

And this is simple mathematics, removing 1000 calories/day from the diet can be achieved with relatively more or less ease (depending on how bad the diet is to start with); the average beginner simply can’t burn that many calories with any realistic amount of exercise.

At a low intensity and a calorie burn of 5 cal/min, that would require 200 minutes of activity per day, over 3 hours. At a challenging 10 cal/min, you’re looking at 100 minutes, an hour and forty minutes. This is simply beyond what most people can, are willing, or have time to do.

This is also why I mentioned the huge assumption that diet is unchanging in the above estimations; another conclusion often reached is that exercise is worthless as the amount of calories that can be burned can be offset by even a small increase in food intake. An average bagel may contain 250 calories (or more if they are the big ones), you can overcome the deficit generated by the lower amounts of activity with a small increase in food intake.

I’d mention that the only impact of exercise on weight/fat loss tends to be due to the deficit created; studies where the calories from activity are replaced by increasing food intake show no changes in anything. That is to say, if you compensate for the activity by eating more (an issue I’ll talk about later), nothing really happens.

In this vein, most of the exercise and diet studies have used fairly low-moderate amounts of activity (in line with the above chart) and few have progressed anything over the course of the study, volume or intensity; most show neglible effects on much of anything (even the much vaunted interval studies only show maybe a 1-2 lbs fat loss over 12 weeks compared to steady state training).

The latter is a problem to me since no good fitness program would be so static without some progression in frequency, duration, intensity or all three as folks got fitter and were able to handle more or harder training. As I mentioned in the Training the Obese Beginner series, one consequence of regular fitness training is an improvement in fitness, allowing folks to train at higher levels (both driving fitness higher as well as burning more calories).

So while realistic amounts of exercise may not be able to play a major role initially in weight loss, over time it not only adds up (albeit in depressingly small amounts) but can end up contributing further down the road as fitness improves. That’s in addition to some other indirect ways that exercise may help that I’ll talk about shortly. Finally, there turns out to be a huge area where exercise has been shown to play a role that I’ll talk about when I wrap up the series.

I’d note before moving on that some studies using fairly large amounts of activity (one that comes to mind had subjects cycle 2 hours/day 6 days/week) have shown a greater impact on weight and fat losses. But these amounts of activities are usually considered to be fairly unrealistic for most people. I’m simply making the point that for people who can do a lot of activity (one person on my forum actually got into the habit of doing 8 hours of low intensity cycling during the day believe it or not) there can be an impact.

But the simple fact is that, for the average untrained individual, realistic amounts of activity are unlikely to have massive direct impacts on either body weight or body fat; the caloric expenditure simply isn’t significant enough to impact on anything. As well, changes in diet have the potential to make a much greater contribution to the creation of a caloric deficit; removing 500 or even 1000 calories per day from the diet can usually be achieved much more readily than adding the same amount of activity. At least in certain populations.

Quality of Weight Loss

Throughout this article I have sort of confusingly jumped back and forth between weight and fat loss (mainly using fat loss as a way of estimating how much exercise might actually impact on things); for the most part the big meta-analyses and a lot of studies have focused more on total weight lost in response to exercise with most of them finding, at best, a small impact.

However, anyone who hasn’t had their head under a rock for the past couple of decades, or who has read anything on this website, knows that there is more to the overall equation than just weight loss. Rather, changes in body composition, the proportion of tissues such as fat, muscle, bone, etc. are what is important. Primarily the changes in fat and muscle.

Just looking at changes in body weight can be misleading. It’s more important to look at what’s happening to body composition. That is, under most circumstances, folks want to lose fat while minimizing or eliminating the loss of lean body mass (especially muscle mass).

Does exercise help with that? That is, does the addition of exercise to a diet change the proportion of what’s lost; that is does it change the quality of weight lost (ideally shifting the loss towards more fat and less muscle mass). And when you look at the studies the answer is a big old it depends. A lot of which has to do with the specifics of the diet (especially the amount of protein provided) and the type of exercise done.

For the most part, exercise is found to have a protein sparing effect of some sort; that is less muscle and more fat is lost in response to the same caloric deficit. It’s not universal with not all studies finding an impact (depending on the, type, frequency, duration and intensity of activity) but certainly the trend is for that.

And here is a place where there does seem to be a difference in what type of activity being done with studies (and practical experience) finding that resistance training (especially coupled with adequate protein intake) being superior to aerobic activity (or a low protein intake) for limiting lean body mass loss and, thus increasing fat loss in response to a diet. And while more mixed, there is some suggestion that this helps to limit the normal drop in metabolic rate that tends to occur with weight loss.

Put differently, as I phrased it in The Rapid Fat Loss Handbook, if there’s a single type of exercise to do while dieting, it’s proper resistance training. Coupled with an adequate protein intake, that alone tends to limit (or eliminate) lean body mass losses such that the weight which is lost (in response to the caloric deficit) comes predominantly from fat mass.

So this is a place where even if exercise doesn’t increase the quantity of total weight loss per se (i.e. how much the scale actually changes), it can impact on the quality of weight lost; with proper exercise causing more fat and less muscle loss than would otherwise occur. Here again, proper resistance exercise, especially coupled with adequate protein, seems to be superior to aerobic activity or diets with insufficient protein. I’ve written about proper resistance training while dieting elsewhere.

Accountability and Adherence

Perhaps one of the most potentially beneficial places that exercise can play a role during weight loss is with adherence. I’ve mentioned this in articles before but, for many people, the simple fact of doing some sort of exercise on a given day makes it more likely for them to stick to their diet. The underlying logic seems to be along the lines of “I worked out today, why would I blow my diet?”

In a lot of ways, this may actually be one of the single most important aspects of successful weight loss attempts, long-term adherence to the plan. I’ve “joked”about this before, saying that the best diet is the one that you can stick to. Except that this is not a joke.

In the big picture, most diets generate about the same weight and fat losses. What matters most is long term adherence. In this context, if regular daily activity of some sort helps an individual adhere to their dietary plan, that benefit alone may be more important than any actual metabolic effects of the exercise bout itself.

Basically, for some people there seems to be a psychological coupling of exercise with good dietary habits on a day to day basis and clearly that can be of benefit. Of course, there is a potential negative that needs to be considered: when/if people stop exercising often their dietary habits fall off just as quickly.

In fact, one odd study years ago looked at this issue comparing diet, exercise and diet+exercise for both short- and long-term results. It found that the diet+exercise group ran into problems such that, when subjects stopped exercising, their diet habits fell apart too.

There is another potential place that this can backfire which I’m going to look at next.

Exercise and Hunger/Appetite

The impact of exercise on hunger and/or appetite is, to put it mildly, complicated. This is because human hunger/appetite (I’m not going to bother making the distinction between the two here) is exceedingly complex being an interplay of biology, psychology and environment. These are often separated out for convenience but they all interact.

Looking solely at biology, overall exercise seems to have a beneficial overall impact on acute hunger, showing a decrease at least in the short-term (other work has shown that the overall hunger/appetite regulation system works more effectively when regular activity is performed).

This seems to be related to increased levels of various gut hormones involved in signaling fullness, as well exercise can increase leptin transport into the brain (other studies suggest that long-term aerobic activity may improve leptin sensitivity which is good given that obesity is generally associated with leptin resistance in the brain). There may still be as of yet undiscovered mechanisms for exercise to impact on hunger/appetite.

Other work suggests that even if exercise can increase hunger, any increase in food intake tends to be less than the energy burnt during the activity itself; that is exercise still has an overall benefit. It’s worth mentioning that even here there tends to be a large degree of individuality, some people compensate for the energy expenditure of activity better than others and this may be part of what contributes to individual differences in results.

One thing I noticed years ago (and forgot to mention in the Training the Obese Beginner series) is that beginners often seem to get a slight increase in hunger following activity, at least in the first few weeks of training. I suspect this is due to their general over-reliance on glucose for fuel (falling blood glucose being one of many stimuli for hunger). At about the Week 4 mark, as their bodies started to get the first adaptation to training and started to use more fat for fuel, this effect generally went away.

It’s worth noting that emerging research suggests that there may be gender differences in this effect (along with many others) with women, as usual, getting the short end of the stick when it comes to exercise and hunger regulation. And this is consistent with earlier studies showing that, under uncontrolled eating conditions, women are less likely to lose weight in response to exercise than men.

Of course, the above tends to interact massively with the psychology of the individual and whether or not they are consciously controlling their food intake. That second issue is a major confound in a lot of studies that people tend to forget about when they compared different studies.

However, this isn’t always the case and one trap that many exercisers often fall into is assuming that their exercise bout has burned far more calories than it has (you’ll hear folks figuring they must have burned at least 1000 calories in an hour of moderate activity when the reality is probably closer to 400-500) and figuring that they’ve ‘earned’ that big post-exercise junk-food meal.

As I talked about above, it’s usually quite trivial to overcome all but the most massive exercise related energy expenditures. You can put down 1000+ calories in a big post-workout meal with ease, more than compensating for the energy burn of the activity.

But as much as anything I feel that this comes down to an issue of misinformation and education; people need to be realistic about the number of calories they are burning during activity. It’s simply almost never as high as they think and realizing this is a first step to avoiding habits that will tend to not only offset but actually reverse any beneficial impact of activity.

Weight Loss Maintenance

As a final topic, I want to look at an issue that is perhaps more important in the big scheme of things than actual weight loss per se. The rather simple fact that needs to be recognized is that weight/fat loss per se isn’t really the hard part; people consistently do and can lose fat/weight all the time.

The issue is with keeping it off. That is to say, although people successfully lose weight/fat all the time, they usually end up gaining it back. Frankly, I am of the opinion that strategies to lose fat/weight are no longer the important issue, rather research and practice needs to find out what makes people so poor at long-term adherence to dietary changes (or behavioral changes of all types) and find solutions to that. Is it biological, psychological, is the distinction even meaningful? And how do we fix it?

But beyond that issue, this is one place where exercise has routinely shown to have a benefit with regards to overall body weight/body fat reduction programs. That is, while most studies have not found a massive impact of exercise on weight/fat loss per se, the impact on weight loss maintenance seems to be much much larger.

Both epidemiological and intervention studies have found that maintenance of regular activity following weight loss is associated with better long-term weight maintenance (I’d note that keeping protein intake high also has benefits) but with one major caveat: it takes quite a bit of activity (I’d note that this seems to assume that the diet is relatively uncontrolled after the active weight loss period).

Various lines of research suggest that a weekly exercise energy expenditure of 2500-2800 calories per week is required to maintain the lowered body weight. If we assume an average of 5-10 cal/min for low to moderate intensity activity, this works out to between 280-500 minutes of exercise per week or somewhere between 40-70 minutes of activity (depending on intensity and frequency) per day.

Again, the above seems to assume that the diet is relatively more uncontrolled following the actual weight-loss intervention which isn’t automatically a good assumption. But it does put into perspective what may be required in terms of daily activity to maintain weight loss.

Similar Posts:

- Steady State vs. HIIT: Explaining The Disconnect

- A 45-Minute Vigorous Exercise Bout Increases Metabolic Rate for 14 Hours

- The 3500 Calorie Rule

- Muscle Loss While Dieting to Single Digit Body Fat Levels

- 3 Reasons Diets Don’t Cause More Weight Loss in the Obese

Lyle, aren’t athletes or elite trainees more efficient, and therefore burn fewer calories?

Good first part Lyle.

I’m a trainer/facility owner who has retained over 90% of his clients over the last 8 years. The number one reason for my retention rate is that I set expectations with clients from the “get go” regarding exercise and weight loss. I get this question all the time from prospective clients who are primarily interested in weight loss (90% of them): “If I don’t change my eating habits and do no other form of exercise besides coming in to see you 3 days/week, what I can expect in terms of weight loss?”

Unlike many other trainers who bullshit a client when they ask the above question and start talking about how “their program” can “transform” the client’s body (in order to get an up front lump sum payment), I tell the client the truth. I explain to them that I can guarantee the following:

1. Increased strength and conditioning

2. Improved movement

3. Improved joint health

3. Increased general work capacity

4. Possible improvement in health biomarkers

5. Possible improvement in sleep quality

6. Possible improvement in energy levels

7. A source of accountability which will increase their consistency and adherence to an exercise program.

8. Possible maintenance of weight/body comp or, more realistically, they won’t gain as much weight/fat as they will if they choose not to train with me.

That’s about all I can guarantee: notice a specific amount of weight/fat loss was not included (remember the specific question they asked me). So, I establish expectations and I can deliver. The client is then happy because they received what I told them they would receive from the start.

The problem is that most “trainers” market their services as a weight loss method or program. They sell the client on their “cutting edge body transformation methods”. Then, when the client doesn’t lose any weight after the first 3-4 weeks, the client quits because the trainer is not delivering. This is why most trainers make under $30,000 annually.

Anyway, I think more trainers need to start coaching their clients on the importance of NEPA/NEAT. Why is that the blue collar manual laborers I see working on the roads around my home (usually with cigarette in mouth) are often times quite lean? I don’t think it’s because they finish their work day and then hit the gym for a hard workout. It’s because they are on their feet all day moving, expending energy, albeit on a lower level. People just need to flat out move more. Everyone is looking to the structured “gym workouts” for the answer, but, as Lyle pointed out, only so much can be done with these from a calorie burning standpoint. If you sit on your ass the other 15-16 waking hours of the day and don’t even so much as get up, the gym workouts are negligible.

How much does initial bodyweight affect the calculations in your article? I usually assume that figures are written for men weighing ~160 lbs., and since I range from 220-240 lbs. I figure I’d burn 40-50% more. Is this a legitimate assumption? I usually put myself down for 1000-1200 calories burned in an hour of biking and about 1200-1500 calories burned in an hour of dribbling (I like to run while dribbling a basketball to get some upper body work in, as well as improve my handle). I usually go pretty hard and am probably better than moderately trained.

Treadmill desk, ftw.

I built one about 6 months ago, and I walk at 1.2 mph for 4-5 hours per day, standing the rest of the time and sitting for only a few hours each day. That’s an easy 300+ calories burned WHILE I’m doing my job.

Also, my back and neck pain from sitting down all day is gone. Everyone with a desk job should get one, or at least a standing desk. You burn calories and avoid the postural issues created by long term sitting/computer ergonomics.

As always, great article, Lyle.

Nicely said, P.J.

Ps good article as well Lyle 😉

You didn’t answer on my other post so here I go again:

https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2002/08/17/saturated-fat1.aspx

What do you think of that article?

Sobhi: The difference is pretty insignificant, there’s an article on the main site about changes in efficiency and how it impacts on real world caloric expenditures. It also takes a long time to occur when/if it occurs at all. And wouldn’t begin to offset the overall improvement in fitness levels. So even if Lance Armstrong is a one or two percent more efficient on the bike, the fact that he can put out double the power output more than offsets that.

PJ: All very good points and I’ll be coming back to part of your list in Part 2.

Bill: Certainly larger individuals will have larger proportional calorie burns (most online resources will put calories burn relative to weight) but tolerance for activity/ability to do a lot of work is often lower as well.

Keenan: Certainly such things may be the future given our propensity for sedentary lifestyle and job situations going forwards.

Bluebeard: Saturated fats are discussed elsewhere on the site in some detail. You might try A Primer on Dietary Fats and Carbohydrate and Fat controversies for my take on the topic. Addressing individual articles beyond what I wrote there is of no interest to me, neither is addressing off topic issues in this comments section.

Thank you for the article Lyle – a wake up call for many I would think.

Good cooments too from PJ Striet.

I do 90 minutes of cardio – 30 minutes high intensity and an hour of low impact plus 30 minutes resistance – every day – a 2 hour workout. I rest every 10 days or so.

I play tennis, bike, swim as well.

I lost 20% body fat, 65 lbs and went from fat to peak fitness.

I eat 3500 calories daily to lose 1 lb a week and eat 4000 to maintain.

It took a little over year, but the results speak for itself.

All Is Possible!

So you can offset about 6 lbs a year with minimal activity, and 55 lbs a year by extreme effort. Why do you consider those numbers negligible? Seems like a person could expect to offset 15-20 lbs a year by starting an light CV exercise program. Sounds pretty good to me. Add a social component by doing some charity 5k’s or playing basketball with friends and there’s the motivation. Really, just spend 3-6 hours a week PLAYING. Then you can up your food intake or lose weight by 15% of daily cals. Oh, and sex counts too, right ?!