This will be an odd little digression where I want to talk about one of my many experiences during my time pursuing ice speed skating. Today I want to tell the skate bearing story.

Table of Contents

You Can’t Buy Performance

I’ve never been a big equipment guy (though I love training toys, go figure). At some point I think I got fed up with people who try to buy performance, either to make up for a lack of talent or being unwilling to put in the work.

And as I so commonly do, I jumped to the opposite extreme often neglecting my equipment. When I was in Salt Lake City, for example, I’d have my ice speed skates blow apart at least once every year because I’d forget to tighten the bolt on the Klap.

And while I still feel that, for the most part, equipment is secondary to other things relevant to performance, there are places where it matters. One of those places is when your equipment is just horrible. In general, cheap stuff is just cheap. It doesn’t work well, falls apart, whatever. And it will hold you back if it sucks too hard.

But once you surpass some price threshold, rarely does throwing more money at the problem generate massive improvement benefits. Sure, it matters for the top 1% where shaving a few ounces of weight is relevant. If you’re reading this, you’re not one of them. I certainly wasn’t.

But there is another place where equipment, even “proper” equipment can be limiting and that’s when you don’t keep it in good (or at least passable) working order. The skate bearing story is an example of that second situation.

Background: Summer Inline Training

Ice speed skating is an odd sport in that a large amount of the yearly training is not done on the ice. This was originally a holdover from the realities of winter sports (you can’t skate on a frozen pond if the pond isn’t frozen or ski when there isn’t snow). Traditionally, speed skaters were often faced with up to 6 months where they had to find ways to train without having access to ice.

My coach used to tell of his own career where he’d spend 6 months off-ice, maybe 6 weeks skating short-track, 6 weeks on the long-track, another 6 weeks short-track and that was it. When you have to wait for lakes and such to freeze, that’s what you have to deal with unless you could afford to go to Europe to train. For a sport that’s insanely technical, it’s far from ideal.

Even outdoor ovals have to deal with weather to some degree, it’s to expensive to try to freeze water when it’s warm out so even with the ovals in the US (Lake Placid, Butte, maybe one more) speed skating was still limited to a lot of off-ice summer training.

Even now, with the advent of indoor ovals (the Salt Lake City oval is open about 10 months out of the year), the reality is that most speed skaters still don’t stay on the ice year round. My coach had told me that the Canadians had tried it when they first built Calgary but everyone was burnt out by October. Skating around on an ice circle just does that to you.

So the sport still revolves around some extended period of summer dryland training before you move to the ice. Programs vary but almost all of them revolve around some combination of bike riding, weight training, skate specific dryland “imitations” (something I’ll write about in more detail eventually) and other stuff.

Inline Skating

That other stuff often but not always includes inline skating. When inlines first came around, back in the early 80’s (the fad didn’t hit until the 90’s and designs actually existed in the 1920’s or so) there were seen as quite the novel thing for ice speed skaters, who finally had a way to practice skating during the summer time. Certainly there were some differences that had to be recognized (especially given how heavy early inline skates were) but they offered another far more specific way to train for ice speed skating.

My coach used inline skating extensively as part of our training, he’d told me that he got most of his technical improvements during the summer time and inline was a big part of that. We’d skate twice per week during our summer training (which usually ran for 20 weeks) at a big parking lot we had scoped out.

During that workout we’d got through full warmups, turn-cable (which was grueling in the heat), a ton of technical drills and then the actual conditioning workout. We also set up a track.

The Inline Track aka The Circle of Hell

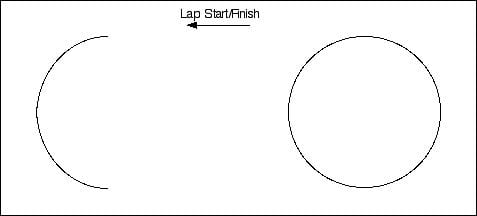

Among the other fun things we did in the parking lot, we also skated an inline track that we’d set up. We used skateboard wheels as blocks (we’d use a rope to ensure that the circles were the same diameter although we finally got smart and spray painted markers to save time) and set up a standard corner at one end and the full circle at the end.

.

We never did actually measure the thing but it was probably 200-300 meters total one time around. The ice oval is 400m but this allowed us to practice everything we needed to do on the ice including corners, straightaways, corner entries and exits.

As one of our many drills, we’d practice corner on the full circle with our coach standing in the middle yelling. We’d often do corners for time, just skating continuously in a circle for minutes. Murderous. We also did right hand circles in an attempt to stave off the low back problems that always plague skaters.

One of the few injuries I had was doing right hand circles when I tripped and cracked a rib. After I plowed into the pavement, my coach asked if I needed to go to the hospital. There’s nothing you can do for a cracked rib but tape it up and go. So I told him to give me the work set and finished the workout. Skating actually didn’t hurt. It was standing up between laps.

We could also use it to skate full laps. While we would occasionally do extended sets of continuous skating, our typical workout was something called lap on/lap off. Here you’d skate a lap at some goal pace, heart rate or effort and then cruise a lap. Skate a lap, cruise a lap. And we’d do this for extended periods of time. I think the most I ever did was a full hour which was about 25-30 laps or so. It wasn’t really that hard. It was just boring.

With few exceptions we’d do this as a full circle lap. So we’d start at the top where I showed the start/finish line skating towards the half circle. We’d accelerate the first straightaway and then skate a standard corner with a proper entry and exit. Back down the straightway and then go all the way around the full circle at the end. So each lap we’d skate a full circle an a half. Then you exit to the straightaway, stand up, coast around and do it again. And we didn’t get to do the full circle on the rest lap.

Rex would shout lap times to give us an idea of where we were (we usually had some goal time for each lap) and if there was more than one of us skating, we’d alternate leads. Usually it was just Caleb and I consistently so he and I would just switch leads and go and go and go.

Skating with Caleb

For the first 3 years or so of skating endless lap on/lap off with him, Caleb just handed me my butt on the inline track. Either he’d drop me entirely or I’d just absolutely kill myself to stay with him (all while he seemed to be barely working). In the first two years this made sense, my corners were awful and since that’s where you get most of your acceleration and speed on the ice, it made sense that he’d drop me on our track.

But about year three, my corners were at least starting to come together. But he was still just murdering me in workouts. At slower speeds I could stay with him if I just gave it my all. At any faster pace, nothing I could do would keep me behind him. In a strong headwind, I’d come to a complete stop. That’s how bad it was.

It was made all the more irritating since I had come from an inline background (he came from downhill skiing, but that meant he knew how to lean into corners). I was supposed to be the one who was good at this. And I was getting killed lap after lap after lap.

From memory, we were skating the full circle lap for like a minute and five seconds or a minute ten or something. At any faster pace I’d get dropped and he could easily pop off sub 1 minute laps with ease. Even if I did manage to stay with him at that speed, it would take all the effort I had. It was really frustrating.

Going into year four, things got strange with our group (well, stranger). Caleb had moved up north and did a good bit of his inline training on his own because the drive down into the valley was so long. The only other skaters who occasionally showed up didn’t have my fitness and most of the time I’d end up skating by myself. At most they might skate 10 minutes while I did a full hour.

My corners were at least passable at this point and this was the first year that a strong headwind wouldn’t stop me in my tracks. And my corners were definitely better on my inline skates than on the ice since I felt more comfortable on them. And despite my fitness, technique, etc. all being up my lap times were stagnant. No matter what I did I couldn’t get past the minute 5 or minute 10 mark on the work laps. And neither Rex or I could figure out why.

Let’s Talk About Inline Skate Bearings

Inline skates, like quad style roller skates and even skateboards, use small bearings, with two going into each wheel (with a spacer in between). While there was a brief design with a single bearing in the center of the wheel back in the 1990’s it never caught on. Here’s a picture of a standard skate bearing.

..

Each bearing has two dust shields on it which you can pop off by getting that little C-ring thing out. It’s a huge pain in the ass involving a safety pin and multiple stab wounds to your fingers. Once you get those out you can get access to the bearings themselves. The picture above is actually called an unshielded bearing which are cheap in every sense of the word. They don’t cost much but they don’t spin for shit.

Now relatively speaking, skating isn’t an equipment heavy sport. Certainly not compared to something like cycling where you can drop as much money as you want to spend on gear (10,000$ for a bike frame is not unheard of). So you didn’t usually see the same type of goofy crap in the sport.

Yeah, people would play with wheel setup and design and boots and frames evolved over the years. That was mainly to accommodate bigger wheels. But there’s still just only so much you can do with equipment. Bearings are where the real stupidity tended to take place.

The ABEC Scale

Bearings are rated by something called the ABEC (Annular Bearing Engineering Committee) scale with rankings existing from ABEC 1 to ABEC 9. There are no even numbers though I couldn’t tell you why. But you can have ABEC 1,3,5,7 and 9 and that’s it.

It’s critical to realize that the bearing ratings primarily exist to define tolerances for high speed machinery. For example, ABEC 9 bearings are rated up to something like 10,000 revolutions per minute. It’s just an extreme level of tolerance for machines spinning at roughly a zillion (give or take a million) times faster than a skate wheel would ever spin.

That didn’t stop companies from making claims about high-end bearings and skating performance. Back in the day, you had to spend quite a bit of cash for ABEC 9 bearings. Recreational skates usually came with crappy unshielded bearings and you had to go buy ABEC 1 on your own dime. At this point, most recreational skates will come with ABEC 3 bearings because they are so cheap.

I still remember when ceramic bearings, where they compress a block of ceramic material into the individual ball bearing, came out for bikes. And I’m sure they were pushed for skates. They were just some insane price but I’m sure they are cheaper now.

And what you’re is potentially getting you is a higher tolerance bearing meant for high speed machinery that also generates less friction. Once again, at 10,000 RPMs this is important. At the speeds a skater might achieve….

My Opinion on Bearings

I never bought that bearing quality made much of a difference beyond a certain point for skating for two reasons. The first is that the ratings are for super high speed machinery. The highest quality bearings are rated for a spin speed that no human will ever achieve and there are far more important factors to performance. Microscopic differences in friction matter at 10,000 RPMs. Not so much when you’re doing 22 mph on your skates.

Another issue is that most bearings are made for linear loading, that is to spin along their rotational axis perfectly. But skating is different. Since the push is down and off to the side, the bearings get a bit of an angular loading across them. Since there are two bearings inside each wheel, the bearing on “top” of the wheel is also getting loaded differently than the one on the “bottom.”

I know this isn’t making any sense whatsoever. Just trust me on this: the nature of skating means that bearings meant for heavy machinery can’t be run at optimal speeds anyhow. They are being loaded fundamentally in a way that they aren’t really designed for.

Which doesn’t mean that your bearings don’t matter. I just don’t think it matters whether or not you’re running ABEC 3, ABEC 9 or Bones bearings or ceramics. At this point you’re paying a lot of money for miniscule differences in machining and miniscule differences in frictional resistance.

And both of these factors are easily overwhelmed by other factors.

Like when your bearings get dirty.

Servicing Skate Bearings

So up above I mentioned that all decent bearings have a dust shield. It’s there because crap can get into the bearings and slow them down. This is especially true for skating where you’re outdoors and there is all manners of dirt and dust and other crapola that can gum the bearings up.

Rain and water is absolutely deadly to skate bearings. Not only does it remove the oil that is inside the bearing but they will rust if you don’t dry and oil them shortly after you skate.

Now when bearings of any quality get dirty they get slow. Because even small pieces of dirt or dust can cause a lot of friction and slow the bearings down. And the effect is much greater than the difference in ABEC 3 vs. ABEC 9 bearings.

For that reason, skaters will clean or service their bearings. Or, if they have tons of money or sponsorship, just get a new set sent out. I’d note that it’s common for skaters to service new bearings straight from the factory/sponsor/bank of mommy and daddy.

Manufacturers tend to use a little heavier oil than you’d want for most skating applications. I would guess this is a heat issue since a bearing spinning at 10,000 RPMs generates a lot of heat. Skating at 22mph on the other hand…

How to Service Bearings

Servicing skate bearings means first popping that stupid C-ring off and then popping off the dust shield to get access to the bearings themselves. Then you use some sort of solvent to clean out what’s in there. That could be the original heavy oil or whatever crud the bearing has accumulated. If you’re an eco-type you can use natural solvents. If you don’t care, you use carburetor cleaner.

Protip: don’t try to clean your bearings with carburetor cleaner indoors.

Once they are clean, you oil them with the oil of your choice. And there are a billion types available. I’m sure that every once claims it’s the best and my gut says that the differences in friction amount to a lot of nothing.

Once the bearings are cleaned and oiled, you put them back in the wheel. Some people will replace the dust shield and C-ring but you don’t actually have to for skating since you can face the open part of the bearing into the wheel. Very little is getting in there and this saves you the headache of dealing with the C-rings over and over again.

Now given my general attitude towards my equipment and the absolute pain in the assedness of servicing bearings, I never paid more than basic attention to them. I remember skating in my mid-20s and a teammate telling me that the Muse brothers (two of the top skaters at the time) would service their bearings until they could get them to spin freely for one minute. If they couldn’t get that they’d reclean and oil them. I always thought that was a bit silly.

But can you see what this is all sort of leading up to?

WTF is Up with My Bearings?

So back to the story of me in Salt Lake City. At this point I’ve been mired in this annoyingly slow lap time on our skating track and we just can’t figure out why given my other improvements. Until one day, for some reason, Rex picked up my skate and spun the wheels.

Let me note that these are the same skates I had raced on in my mid- to late-20’s before my first retirement.

The wheels made some horrible grinding noises and ground quickly to a halt. They spun for maybe like half a second. He asked me gently when the last time I had serviced the bearing was. I told him that not only could I not remember but that, realistically, it was probably 1995. This happened in like 2009 so a mere 14 years since they had been serviced. And no guarantee that I had done a good job of it even then.

He was, to put it mildly, taken aback. He described a very specific cleaning method to me, that he’d developed over 3 decades of experimentation and told me to take care of it before the next session. I did and showed up to the next inline session not really knowing what to expect.

We went through the normal workout and then it was time for lap on/lap off. Neither of us knew what to expect so I just launched into my first lap. There was a distinct improvement, at the same or a lesser effort level I was throwing down mid to high 50 second laps. So just servicing my bearings took nearly 10 seconds off my lap times. Clearly the bearings had been a problem.

I Feel the Need, the Need for Speed

But Rex still wasn’t satisfied. At the next workout he presented me with a brand new set of bearings, serviced by him with instructions to mount them before the next workout. Which I did.

So we went through the normal workout until it was time for lap on/lap off. He said he expected another drop, for me to maybe put down a 50-51 second lap. I don’t know if he was guessing or what. So I launch off on my first lap, up the first straight, around the corner, back down the second straight.

I should mention that our parking lot wasn’t perfectly level and there was a slight downhill into the full circle.

And I hit that corner on the full circle and well…I nearly shit my pants from terror. As Rex liked to put it, there was a high pucker factor. It took literally all I had to even hold the corner at all and when I finished the lap he called out something just stupid like 46-47 seconds. That was with the full circle.

So with nothing more than a new set of super cleaned and serviced bearings, my lap times had dropped roughly 20 seconds from 1:05-1:10 to 46 seconds. It was something nuts like a 28-30% improvement. I can’t do the math on the speed increase since I’m not sure of the track distance but it had to have been multiple miles per hour. Hence the high pucker factor.

Oh yeah, shortly thereafter, Caleb would join us at inline practice. But he wasn’t aware of what had happened. He had been used to just farting along at 1:05 so I could keep up with him and let’s say it was a bit of a shock for me to be throwing down 46 second laps. So we spent the better part of an hour just hammering each other into the ground at 46-47 seconds per lap, trading leads to see who would crack first. But that’s a different story.

Summing Up

So I don’t know if that’s much of a story but hopefully it has somewhat of a point. Well, multiple points. The first is that I’m often an idiot who gets in his own way by being pigheadedly stubborn. But that’s not really news.

Perhaps the bigger point is this: while you can’t usually buy performance, there are clearly times when your equipment matters and can make a pretty considerable difference. This was obviously one of them although it was more an issue of having basic equipment in good working condition than anything beyond that. I was still only riding ABEC 3 or something. I was finally just riding ABEC 3 that were clean and spun. Moving to ABEC5 wouldn’t have made an iota of difference so far as I’m concerned.

Certainly most situations won’t be that extreme, where a change can get you a ~30% improvement. The above is what happens when there is a serious problem. And part of the impetus for writing this story up was a post to a power training group where a guy talked about how cleaning his bottom bracket got him a 20 watt bump on his power outputs.

To have gotten any further improvement out of my equipment beyond correcting that problem would mean a lot more time, energy and/or money and the return would be far smaller. I still don’t try to achieve the 1 minute free spin that the Muse’s used although I’m certainly more attentive to bearing maintenance and function. If I can get my wheels to spin for 45 seconds I’m happy. If one of them grinds to a halt at 10 seconds, I’ll switch out the bearings until it doesn’t.

There ya’ go, that’s the bearing story.

Facebook Comments