In various places on the site, I have made the comment that such things as caloric intake and activity will have to be adjusted based on real-world fat loss. This is a big part of the reason I tend to quick-estimate maintenance calorie intakes to begin with. Any value you come up with whether you quick-estimate it or use some complex approach is only a starting point. If you have to adjust it anyhow, the quick method is usually good enough.

But that raises the question of how to actually adjust the diet based on real world changes in body composition. Even that is contingent on being able to get an accurate measure of body composition. For the most part, I’ll be addressing moderate dietary deficits. But the same information would mostly apply if large or small deficits were being used.

Table of Contents

A Quick Note About Water Balance

Before I get into the meat of the article, there is one topic I want to bring up first. Many people have an expectation of fat loss being this nice weekly linear thing that occurs in a predictable fashion. And certainly, for some people this can be the case. However, for an equally large number of people (and I’d probably tend to argue that these folks are in the majority), fat loss does not occur in a predictable linear fashion.

Rather, there are often stops and starts or, as it’s often referred to on the Internets, stalls and whooshes. As silly as the name sounds I discussed it in some seriousness in The Stubborn Fat Solution. The main culprit here is almost always water retention which can mask fat true fat loss and make it look as if a diet that is otherwise set up perfectly (and working just fine) actually isn’t.

People vary in how predisposed they are to this occurring. Some folks seem to retain water like crazy, especially if they try to combine hard deficits with excessive and or too intensive of activity.

Women’s Issues

Women of course have an additional factor of shifts in water balance throughout the menstrual cycle. Even that is massively variable, some women gain little to no water weight throughout the month, others can hold an extra 5-10 pounds (2.5-5kg or so) easily. I discuss this in detail in The Women’s Book Vol 1.

When you couple that with women’s generally slower rates of fat loss, this can make it extremely difficult to determine if their fat loss diet is working or not. So consider a woman on a moderate deficit which should be generating one pound of fat loss per week. If her weight is varying 5 lbs every other week due to menstrual cycle fluctuations, she has literally no way of knowing if the diet is working.

Of course, if the water retention is related to menstrual cycle stuff, what she should see if times of the month when her weight/fat is down (below where she started) and other times when it’s not. Plotting weight or some attempt to measure body composition on a monthly basis to see what the overall trend is is probably going to be more beneficial than looking at it on a week to week basis. Really what women have to do is only compare the same weeks of each cycle to the same weeks of the next cycle. That is, Week 1 weights or body composition to Week 1. Week 2 to Week 2. You get the idea.

The Point

My point in bringing this up is actually not just to depress people. Rather, I’m pointing out that what I’m going to discuss in this article in terms of adjusting the diet can be done too often. For folks who have issues with water retention (who may see big drops every couple of weeks rather than smaller drops weekly), trying to gauge true weekly fat loss and adjust the diet is usually a losing proposition.

Rather, those folks may have to only look at what’s happening every 2 weeks to decide when and if to adjust their diet. Women with major menstrual cycle swings may even have to chart their monthly trends to see what’s happening and only make adjustments every 4 weeks.

Yes, I know this is a pain but at this point there’s really no solution for it. All of the methods that we have to measure body composition are too inaccurate to get around this and the point I want everybody to really take home is that expecting predictable weekly fat loss may not be realistic depending on individual propensity to hold water or not.

What Is the Predicted Fat Loss?

Accepting the above, that water balance can throw off expectations on a week to week (or even month to month) basis in terms of fat loss, the first necessary data point is what the predicted or expected fat loss actually is. I showed some representative values for this when I talked about different size dietary deficits. Clearly a larger deficit will (or should) generate more weekly fat loss than a smaller deficit.

But even there the calculations are rough. The idea of 3,500 calories equalling one pound has a set of problems, all of which I discussed in detail relative to energy balance.

That said, I for the purposes of this article, I am going to us a relatively average sized mail dieter who has set a moderate calorie deficit which predicts a true weekly fat loss of 1-1.5 pounds. This should at least be reasonable but, again, the numbers will differ for larger or smaller dieters and larger or smaller deficits.

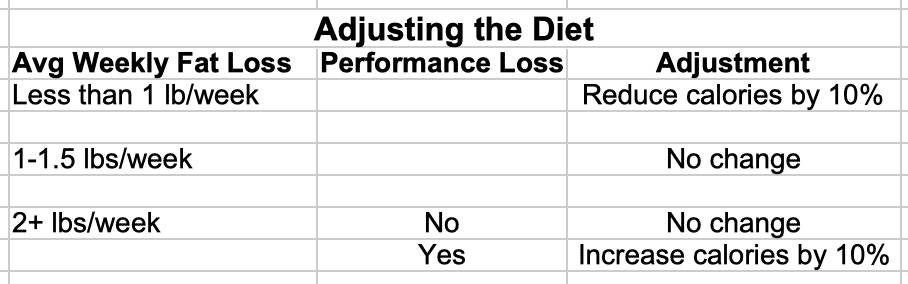

So our dieter is, well, dieting. And let’s say that after three weeks, they have determined some amount of fat loss. In an ideal world, it should be between 3-4.5 lbs of true fat loss. How can or should they adjust the diet based on the real world changes in body composition and whether or not there is performance loss in the gym.

Frankly, there’s nothing that exciting in the chart and it should be fairly self-explanatory. If your predicted fat loss is 1-1.5 lbs/week (and you’re not messing up your calories somehow, through mis-measurement or what have you) and your actual fat loss is less than that, you should reduce calories by 10% and then re-adjust in 2-3 more weeks. Eventually you’ll hit the sweet spot.

Clearly, if you’re hitting your goal numbers right on the spot, don’t change anything.

Of course, there are times when the actual weekly weight loss ends up being larger than expected. Some of this can be water or what have you but not always. And that leads me to an explanation of the middle column.

And that brings in the middle column which asks if you are experiencing performance loss. A primary metric when dieting, whether in the weight room or out, is that performance should be maintained. In the context of the weight room that means maintaining poundage on the bar. While imperfect, this is a fairly good indication that no muscle is being lost.

Now this isn’t always possible and some degree of performance loss is normal as people get to the lower limits of BF% (i.e. sub 10% for men, sub 15% for women). As well many notice that compound movements like squats and the bench press get hit harder than machine exercises. Even if your squats are down, if your leg press or leg extension strength is the same, you’re not losing quad mass.

But outside of that, if major performance drop offs are being seen during a diet and the training is correct, that is generally a bad sign. Importantly, it can indicate muscle loss. In that situation, the daily or weekly deficit should be reduced. Either calories should be brought up by 10% or excessive activity (usually cardio) should be reduced.

The same holds for athletes who are dieting for fat loss. If some important metric of their performance such as run times, cycling power outputs, etc. is worsening then their deficit is too aggressive and should be reduced. Either calories must be brought up or “junk” activity should be reduced.

Strictly speaking, I could have included a performance loss for any of the weekly fat losses. So there could be a situation where someone was losing their goal 1.5 lbs fat per week and seeing performance crater. Some people just seem more prone to it for whatever reason. In that case, they can either accept that performance loss with the hope that it will come back when the diet is over. Alternately they may have to use a less aggressive deficit overall.

Let me finally note that once the sweet spot of fat loss is hit, that doesn’t mean it will stay there. As the body adjusts metabolically to fat loss, eventually a further adjustment to calories or activity will need to be made. So at the point that weekly fat loss drops from 1.5 lbs/week to below 1 lbs/week, a further 10% decrease in calories or 10% increase in activity will have to occur. I’ll provide more specific details on this in a later article.

How to Adjust the Diet

And that’s how I adjust diets. Honestly, there’s nothing too majorly complicated to it and there are basically three steps.

Step 1

First off you need to have some idea of what the expected or possible fat loss for a given deficit is. I’d note that people always want fat loss to be faster than it is no matter what they do. If they are losing 1 pound per week, they want 2 pounds per week. If they are losing 2 pounds per week, they want 4 pounds per week. If they are losing 5 pounds per week, they will want 10 pounds per week. This is just human nature but it’s not always realistic.

Yes, larger deficits can be used to generate faster weekly fat losses. My own Rapid Fat Loss Handbook diet can generate 2-5 lb fat losses/week depending on the person. But even there you have to know what the predicted or expected fat loss is meant to be.

Step 2

Then you need to track actual real-world fat loss. Mind you, keep in mind the issues with water balance, stalls and whooshes. For women, the menstrual cycle must be taken into account. But trying to gauge the success of a diet on a weekly basis is a losing proposition for most people. Some can but most probably cannot. Rather, you need a 2-3 week measurement to be able to really know if you’re hitting your targets. Women might have to wait a month to compare the same weeks of the cycle.

Step 3

Now compare the real world fat loss to the predicted fat loss. If you’re not doing something like mis-measuring your food (which is common) and you’re lower than your goal, increase the deficit slightly. Wait 2-3 weeks and adjust again.

If you’re in the sweet spot, losing what you’d predict or expect, don’t change a thing.

If you’re losing more than predicted and/or seeing large scale performance loss, you will need to reduce the deficit. Either increase calories or reduce extraneous activity.

In all cases, don’t make huge adjustments at once. An extra 10% in either direction is fine. Then gauge results again and adjust again until you hit the sweet spot. Let me repeat that eventually your current calorie/activity level will stop generating the desired results at which point you’ll have to adjust it again.

Similar Posts:

- The 3500 Calorie Rule

- Estimating Maintenance Calories

- Of BMI and Weighing Frequency

- Muscle Loss While Dieting to Single Digit Body Fat Levels

- Pros and Cons of Three Sizes of Calorie Deficits

“let’s say a woman is on a moderate deficit diet and shoud be losing right around 1 pound of fat per week. If she is holding an extra 5-10 pounds of water, it could take 5-10 weeks before she actually sees that her diet is working.”

Thanks for writing this, Lyle. I am in the “last 10 lbs.” phase of losing weight after taking off about 55-60 total. During my last cutting cycle it took me three weeks to see a 1 lb. loss and I got really frustrated. I know that I retain water really easily (i.e. one meal of Chinese food = +5 lbs. on the scale the next day) but I never realized that water retention could so dramatically mask weight loss. I realize now that if I’m going to calorie restrict again I should go almost entirely by measurements and weigh in maybe once a month, rather than weighing daily like I was.

This was a good confirmation to me. I am post menopause (3 years) and find that losing is much harder than before meno. But I do still see some cycling of “premenstrual” symptoms and I would guess that includes some water weight gain as well.

For me taking my measurements and weighing once weekly, I can see my losses in a more definitive way–rather than ride the emotional rollercoaster when watching the scale zig zag.

I have used the method Bill Phillips spoke of ten years ago, where someone could use a “Free Day” so to speak, if their diet and nutrition was adhered to for the remainder of the week. I generally did not have negative results when following that pattern, but I do wonder if I could have reached my goals quicker had I simply stuck to my guns on all days of the week. The free day was a positive thought of something to look forward to, but I didn’t know if he meant one meal, or a free for all the entire day. In any case, I also wonder if there is anything bad or negative I could have been doing by following that plan that never occurred to me.

Is it normal to see changes within 12-13 hours after starting a diet/exercise program? I swear to the g-man,..after one of my 12 hour work shifts of running around, climbing stairs, etc, at the paper mill..I always look leaner. It’s not just me,..people around me comment and ask what’s the deal, i look like I’ve lost some weight on a diet or something. But this usully only happens when I dont eat at all or just eat a snickers and coke the whole day. Maybe I loose/retainwater real quickly? I also hover at less then %15 bf in my opinion though.(i have discernable abs especially when i flex them.) the complexities of dieting make me dizzy.