In A History of Women in Sport Part 1, I looked at the changes that occurred during the 20th century in term’s women’s involvement and acceptance in sport. Today I want to follow that up by looking at the changes that have continued to occur into the modern era.

Table of Contents

Women in Sport Part 5: The Modern Era

As I write this chapter in 2018, the status of women’s sport has changed even further with more progress having been made. At the Olympic level, women now make up 45% of the total athletes attending the games (3). A similar pattern is seen in American sports with 45% of both high-school and collegiate athletes being female (4,5). I have no statistics but get the sense that the same general pattern is occurring in many other Western countries.

In the same way, I suspect that those changes are still not occurring in less economically disadvantaged countries or where older social stigma still exists about what is and is not an appropriate role for women. But in the aggregate, the increased involvement in women’s sports is enormous increasing from essentially zero at the turn of the 20th century to nearly equal numbers in the early part of the 21st.

Whether women will achieve truly equal representation in sport at any level remains to be seen. In American high-school and collegiate sports, I doubt this will actually occur. This is primarily due to the presence of American football and the staggering number of males who play it.

I don’t have numbers available but suspect that with that single sport removed from the equation, women would achieve near parity with men in terms of their involvement in sport overall. In fact, given other sociocultural changes that are occurring, it will not surprise me if women match or even exceed men’s involvement in at least some sports.

At least in the Western world, it’s becoming more common for girls to enter sport while boys would rather play video games and it will not surprise me in the least if the percentage of women involved in at least some sports exceeds that of men. At the very least, I cannot envision a situation where things would reverse themselves. The cultural changes and acceptance of women’s sport has become far too entrenched for that to occur.

At the Olympic level, the remaining differences are probably related to a small degree to some events not having events for both women and men. I suspect more of it is due to some countries not having a large degree of women’s representation and I have no idea if this will ever change completely enough for women to represent truly 50% of the athletes competing.

For the most part there seem to be very few sports where women are not represented. In the endurance sports, the majority of events includes women’s competition. One oddity worth mentioning is the women’s steeplechase, a track and field event involving three hurdle obstacles and a water jump that was not added to the Olympics until 2006. I have no idea why this was added so late to the game but suspect it was a practical issue rather than being related to any remaining ideas about women’s bodies being unsuited to endurance events.

The summer Olympic games tends to be overfull with too many events and there often simply isn’t space to add one without removing another. Often there are financial reasons for the inclusion of a given sport or not as well. The Olympic games is big money and often sports are chosen based on what viewers will watch and, by extension, what will generate ad revenue.

Regardless, by the time the steeplechase was added, women’s track and field was identical in scope to men’s except for one event: the decathlon. Contested since 1912 by the men, the decathlon is a 10-event track and field competition that is meant to determine the best all-around athlete. But for most of history women did not compete the event. Until 1981, women competed in the pentathlon, a 5-event sport which was eventually upgraded to the 7-event pentathlon.

I’d note that there is a men’s heptathlon but it bears little resemblance to either the women’s heptathlon or men’s decathlon as it is competed indoors. It wasn’t until 2001 that the international governing body of track and field created scoring tables for the women’s event and the first USA Track and Field decathlon is only scheduled to be run as I write this in 2018 (6).

So far as I can tell, the women’s decathlon did not exist less out of fear that women could not do the event as being due to the existence of the heptathlon making it unnecessary. Advocates for the creation of the decathlon contend that women should have an equivalent sport to determine the best all-around athlete but there is resistance to this even within the sport.

In an Olympic context, there is only room for one multi-event sport in track and field and some fear that adding the decathlon will eliminate the heptathlon from the games which could be unfair to current heptathlon athletes.

It will also require current heptathletes to learn several new and very technical events (including the pole vault). For established heptathletes, the replacement of the event with the decathlon could put them at risk due to having to learn new events late in their career.

Of more concern is the fact that the events of the women’s decathlon is being run in a reversed order so as to not overlap with the men’s event at major competitions. For both women and men, this reversed order is far more dangerous due to fatigue from certain events making later events more dangerous. But since the men’s event is already in existence, only the women’s event would be subject to this reversal.

As with the decathlon, there are other sports, frequently newer sports, where women have only relatively recently become involved or accepted at any level. Frequently these are the more combat oriented sports where women either showed little interest or were simply not allowed to compete up until the modern era. I mentioned that women’s boxing was only added to the Olympics in 2012 and sports such as American football and mixed martial arts (a very new sport for both women and men) are relatively recent developments in women’s sports.

Women’s rugby is an odd exception to this and has been played in some form or fashion since the 1960’s with some indication of women’s rugby matches occurring in the late 1800’s. There were club championships in the USA and Sweden in 1980 and the first women’s world rugby cup in 1991 and I have no idea why this one sport stands out from the others.

There are also situations where women’s events are still set up to be easier or less challenging than the men’s. The marathon is the same fixed distance for all competitors but in some endurance sports, there are often differences in the distance contested for women versus men.

In road cycling, for example, the women’s course at the 2016 Olympics was 87.6 miles (141km) compared to 150 miles (241.5km) for the men (interestingly the time trial course was an identical length). In track cycling, the points race for men is 25 miles (40 km) but only 15 miles (25km) for women. And while the team pursuit is identical length for women and men, the team sprint is 2 laps for the women compared with 3 laps for the men.

In the odd sport of ice speedskating, the men’s all around competition consists of the 500m, 1500m, 5000m and 10,000m while the women’s consists of the 500m, 1000m, 3000m and 5000m race. There is no official women’s 10,000m event and the 3000m is often seen as a “women’s event” that men rarely race except to set world records. In a physiological sense, there is absolutely no reason for this to be the case and it assuredly traces back to tradition and early 20th century ideas about women being too fragile to skate the longer distances.

In at least some sports, women use different implements than the men although this often has a fairly logical basis. In track and field, women use a lighter and smaller shotput and discus for example although this has more to do with women being smaller, lighter and having lower levels of maximal strength than men.

Women’s basketballs are a smaller diameter to account for smaller hands and grip issues as are the footballs used in American football. I will address some specific women’s concerns regarding equipment later in the book and these differences are more of a concession to the realities of women’s physiology and anatomy than anything representing long-standing ideas about women being incapable of performing certain sports.

Women in Sport 6: The Strength/Weight Room Sports

But while women are essentially accepted in almost all types of sporting events in the modern era, there is one area where they have not been either traditionally represented and, in many cases, are not well accepted. Or rather have not been until fairly recently. This is in what I will term the strength sports. This would include such activities as the shotput and discus and I mentioned above that women were only allowed to compete in these events fairly late in the game.

But here I want to focus on those sports that specifically involve some type of weight training and that means I will focus on Olympic weightlifting, strongman, powerlifting and bodybuilding. Of all the sports in existence, these probably have the most long-standing and still-remaining attitudes regarding femininity and masculinity both at a cultural and “medical” level. I will actually address this in more detail later in the book and here only want to look at them within a historical context.

Olympic Weightlifting

Olympic weightlifting (or just weightlifting) is the only pure weight room activity done at the Olympics. It originally consisted of three lifts (the snatch, clean and jerk, and press) although the press was dropped in 1972 and only the first two lifts are done in modern times. Both entail lifting a weight overhead in different ways and the point of the sport is to lift the most weight possible to determine who is the strongest (the sport has weight classes to make competition more fair).

While the sport has changed since its inception, it has been contested in some form since 1891 for men and was included in the earliest modern Olympic games at the turn of the 20th century. In contrast, the first women’s World Championships were not held until 1987 and a women’s event was not added to the Olympics until the year 2000. In a sport where men have over a century worth of tradition and competition, women have only had official involvement for roughly 20-30 years.

Strongman/Strongwoman

At least broadly similar to this is the sport of strongman. The sport revolves around various tests of strength, typically lifting odd implements such as stones, weighted logs, tires, heavy weights, etc. and contests vary but it is meant to determine, literally, the strongest man. In any sort of official way, strongman appears to have been created in the 1970’s but it would not be officially contested for women until 1997.

In The Women’s Book Vol 1 I often referred to it as Women’s Strongman and it is only sometimes called Strongwoman competition now. While this only represents a ~30 year gap between women and men entering the sport, this has more to do with it being a relatively new sport overall. Had the event existed in the early 20th century, it’s almost a certainty that women would not have competed in it until fairly recently.

Powerlifting

The sport of powerlifting is very similar. Coming out of a tradition of odd lifts, powerlifting competition revolves around the three lifts of the squat, bench press and deadlift with the goal being to lift the most weight a single time (like weightlifting, it has weight classes). It’s a little difficult to say exactly when the first modern powerlifting competition occurred although it was somewhere in the realm of the 1950’s to 1970’s.

So far as I can tell, the first female to be involved in the sport was Jan Todd in 1975 but she was a lone exception and likely only accepted due to her husband (the recently passed Terry Todd) being involved in the sport himself. Beyond that, I have no actual statistics on women’s involvement but when I was taking female lifters to events in the early 2000’s, it was rare to see more than a relatively small number of women at all (though Texas has a relatively larger number of female powerlifters).

Bodybuilding/Physique Sports

Finally is bodybuilding and by this I mean competition bodybuilding where contestants stand on stage to have their physiques judged and compared. As the competitions themselves revolve around little more than posing, we might debate if it is truly a sport in the sense of the other activities listed.

However, the majority of training is done in the weight room and for that reason, it is worth examining. The first official bodybuilding competition was, perhaps surprisingly, held in 1901. These were held throughout the 20th century and events in the 1950’s to 1970’s and women were included. But this was more of a beauty or bikini event than anything related to bodybuilding.

There actually were women’s physique competition being held in the 1960’s but these were also more likely to have been beauty competitions more than anything else. The first official female bodybuilding event would not occur until 1977 and even then it was an incredibly niche sport.

The first Mr. Olympia competition, considered the pinnacle of the sport, would be held in 1965 while the first Ms. Olympia would not occur until 1980. Even here it would remain an incredibly niche activity, never reaching anything that even approximated the level of interest as the men’s events in either women’s involvement or spectator interest.

This has to do with the fact that, perhaps moreso than the other strength sports, women’s bodybuilding has always faced a huge issue regarding what is “feminine” or “masculine” with as much sociological and cultural factors playing into this as anything else.

For men to focus on becoming larger and more muscular was seen as completely logical from a cultural and biological point of view but this ran counter to most of the ideas of what constituted femininity. There are decades of debate, none of which I will even attempt to address, over the degree of muscularity that was acceptable for women.

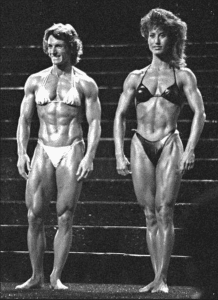

Early female bodybuilders such as Rachel McLish (right) were relatively lightly muscled although there would be a progressive increase in muscular size over time. Bev Francis (left), an ex-powerlifter, arguably started the change towards far more muscular physiques.

This would be further impacted by the heavy use of anabolic steroids in the 1980’s and onwards which would lead both the women and men in the sport to become increasingly more muscular. While this was deemed acceptable for the men (even as some fan’s become disillusioned with what they perceived as a lack of aesthetics), it was becoming increasingly problematic for the women.

Judges would flip flop from year to year on what they considered optimal or indicative of an “appropriate” woman’s physique and endless debates went on over whether female bodybuilders should be judged on the same criteria of muscularity, symmetry, etc. as the men or by some other criteria that was deemed more “feminine”.

A rather staggering amount of sociological critique has been written on this topic and I am certainly not the one to address it. I’ll only note that professional female bodybuilding, even moreso than the men’s divisions, eventually killed itself off. Never more than a niche activity or interest, it simply reached too much of an extreme for most to care (the same has happened to some degree in the men’s divisions) or watch.

But in response to that general apathy, other categories such as women’s fitness, physique and bikini would be developed based around much less muscular and more “feminine” physiques. A classic physique category exists with the competitors looking similar to the late 70’s/early 80’s bodybuilders of a previous era.

Currently interest in the sport is at an all-time high for not only this reason but other shifting cultural reasons with it becoming more acceptable for women to carry relatively greater degrees of muscle (in this vein it’s interesting to note that current winners of the Miss America beauty contest are relatively more muscular than they have been in the past). I’d note in this regard that even the idea of recreational weight training for women was more or less off the table until very recently.

With the possible exception of combat sports, it is the strength sports, and the weight room sports specifically that have carried much of the baggage of earlier beliefs with them. Inasmuch as competition per se was seen as a male domain, the weight room and activities related to it has been seen as an even more male dominated or exclusive domain.

This was true at both the competitive and recreational level where the idea of women lifting weights at all was often seen in a negative light. And the fact is that in recent years this has changed to a staggering degree in all domains from competition to recreational lifting.

Women’s involvement in both Olympic lifting and powerlifting is currently enormous. At mixed events, nearly equal numbers of women and men are present. Since there are finally enough competitors to make it tenable, women’s only events are being held in both sports as well. I can’t speak to strongwoman competition per se but get the impression that women’s involvement is increasing here as well.

As a more niche sport, and one that requires some often difficult to find equipment, I’m not sure it’s grown to quite the same degree as the others but it’s clear that women’s involvement has increased and will continue to do so over time. The simple fact that the sport is now sometimes being referred to as Strongwoman competition attests to that.

The physique sports have absolutely exploded in recent years and this has happened for a few reasons. One is that there has been a rebound away from the extreme muscularity of the past. This has happened in both the women and men’s versions of the sport.

Here men’s classic physique and fitness becoming quite popular and essentially returning to the physiques of the late 70’s and early 80’s before the push for maximum size became prevalent. Along with that, specifically to women, are changes in cultural attitudes regarding what constitutes femininity or the degree of muscularity that is acceptable. As I will discuss this in more detail in a later chapter, I will stop here for now.

Going Forwards

While it took the better part of a century, women have gone from being considered too delicate to even engage in sport to competing at the highest levels in nearly every sport that exists. In any sport of any type, it is now commonplace to find women competing and succeeding as society and global culture continue to change. Even outside of the realm of competitive sport, and ignoring the large majority who do no exercise at all, women are becoming involved in activity at an increasing rate in both competitive and recreational sport.

From the start of my career in the mid 1990’s until now (I am writing this in 2018), I have watched the presence of women in the weight room increase to a staggering degree, perhaps moreso in the last half decade than in all of the years before it.

It would be very difficult to take issue with this on any level as there was clearly no fundamental reason outside of inherent sexism and bias to preclude women from sport or activity in the first place. Which isn’t to say that there are no concerns to be had regarding women and their involvement in sport or exercise. In this context it’s worth returning to some of the old supposed medical ideas regarding women in sport that I discussed above.

Women in Sport: Medical Issues Part 4

In hindsight, it’s fairly clear to see that the early medical practitioners of the day, almost always men, were speaking from bias rather than science. It was mostly just entrenched sexism at work with the justification coming after the fact.

The biological theories for why women should not do sport were based on no actual data but simply inference. Even when data existed as it did by the early 1930’s, it was ignored in favor of pre-conceived beliefs. The idea that competition, sporting or otherwise, was somehow foreign to female physiology was fundamentally nonsense.

The idea that women were ill suited to endurance sports was not only incorrect but backwards. In many ways, women are more suited to endurance activities than men (in at least one ultraendurance event, women have outperformed men). The idea that engaging in sports would masculinize women on any level was absurd. Women have competed at the highest levels of sport while maintaining what most consider societal ideas of femininity.

Quite in fact, as I mentioned in The Women’s Book Volume 1, it’s not uncommon the appearance of female athletes to be commented on moreso than their athletic accomplishments (simply a different type of sexism). Social scientists have written endless critiques of what does and does not define femininity.

They frequently point out that female athletes not only maintain but leverage their femininity to their advantage (essentially catering to what is traditionally defined as being feminine to gain benefits). This is absolutely not a topic I intend to address in this book as others who are far more qualified have written about it in far greater detail and with far more insight than I ever could.

It would seem in hindsight that all of the doctors, invariably male, who proposed ideas of why women should not engage in sport in general or any specific sport were totally incorrect. Or were they?

Certainly as they described the issues, based on the limited information (read: ignorance) of the day, they were flatly incorrect. That is, the actual physiological justification that were given at the time were almost invariably wrong. However, as we’ve seen over the past decades, there were at least elements of truth to what they were saying. Or rather, there were concerns that would not become apparent until women began entering sport in larger numbers. Let me look at some of them in brief.

First consider the general belief that excessive exercise would cause women to become infertile or lose their reproductive capacity. Certainly, the idea that her reproductive organs would wither was nonsense. However, as I detailed in Volume 1, as women started entering sport in larger numbers in the 80’s, there was an enormous increase in the incidence of menstrual cycle dysfunction.

This led to the development of the Female Athlete Triad (FAT, now RED-S) concept which encompassed insufficient calorie intake, menstrual dysfunction and bone loss. Women were in fact becoming amenorrheic, and hence temporarily infertile, although not for anything approximating the reason that had been originally given.

We know now that this has to do with low energy availability (EA, the difference in calorie intake and exercise energy expenditure) which is more related to dietary intake than training per se. That is, when female (or male) athletes match their food intake to their activity, they do not become amenorrheic and the amount of training being done per se is not the driver on hormonal or other dysfunction.

It’s also not as if women did not suffer from eating disorders or amenorrhea long before they became involved ins port. In this case it is simply a situation where certain sports (usually those involving thinness) and undereating go hand in hand, causing what is a very serious deficiency in energy intake.

When this occurs, the body has to make choices about what biological processes to maintain or shut off. As reproductive capacity is not required acutely for survival it is one of the processes that shuts down. In the broadest sense we might even compare the EA concept to the early idea of a woman’s body needing a certain amount of “available biological energy” for reproduction to occur. No it is not some limited quality that can be depleted permanently and the early savant’s ideas were clearly flawed. But conceptually they were not drilling an entirely dry well.

Clearly the ideas that women were unsuited to endurance sports was not only wrong but backwards. As I noted above and will address again later in the book, in many ways women are more suited to endurance activities than men. At the same time, they are more likely to suffer from exercise associated hyponatremia (a situation where electrolytes in the bloodstream become severely imbalanced) along with having a worse outcome when and if it does occur.

The idea that turning upside down during a pole vault or falling 2m 1000 times by practicing ski jumping would be damaging to a woman’s reproductive organs seems equally nonsensical at first glance. However, stress urinary incontinence (the involuntary loss of urine) is found frequently in female athletes, especially those involved in high-impact sports or those that involve repeated jumping such as trampolining. And it is actually due to damage to the pelvic floor muscles, ligaments and even nerves. To some degree at least, there was an element of truth to the idea.

Fears regarding combat sports seem equally absurd. Boxing and wrestling were not added to the Olympics until fairly late and much of this this was based on fears that they were too physically damaging for women. Counterarguments held that boxing per se was inherently damaging to both women and men and that these fears were more cultural than biological with no gender difference being present.

However, we now know that women are more likely to sustain concussions than men in certain types of sports involving heavy impact (i.e. boxing, rugby) along with having a worse outcome if one does occur. So the fear was at least somewhat real.

The idea that team sports and the physical contact involved would be damaging seem equally ludicrous in hindsight. At the same time, as women entered team sports in larger numbers, they started to show a vastly increased risk of knee injury, including the devastating and often career-ending anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. As I’ll discuss later in the book, women show anywhere from a 3-9 times risk of ACL tear as men which is simply enormous.

Of some interest, women suffer the injury for fundamentally different reasons than men (non-contact for women versus contact injury for men). It’s clear that women do in fact face dangers than men do not in this regard although it actually has less to do with the contact nature of such sports. This goes along with women showing an increased risk of other types of knee injury/pain and ankle injuries.

Women are also at a higher risk of stress fracture than men. Many of these issues have become especially relevant as women have begun to enter the military in larger numbers and the same increased injury risk and type are being seen.

It should go without saying that the idea that training for sports would masculinize a woman is nonsensical along with being biologically impossible. At the same time, as I discussed in Volume 1 and will address again in this book, women with a more “masculine” physiology due to PCOS or other conditions (some of which become very complex indeed as they represent an intersex category) have an advantage in many sports.

Certainly many early female athletes often showed some of the “masculine characteristics” typical of PCOS or other endocrine issues (none of those conditions having been identified at the time) and it’s possible that the medical experts drew their ideas from this. But in doing so they confused cause and effect.

In certain sports a more masculine physiology, body build or even demeanor is an advantage and that will tend to attract women with those characteristics who will then succeed and continue to engage in it. It wasn’t that sports were masculinizing women but that women who carried more masculine characteristics were often going into certain sports.

One might very obliquely argue that the use of anabolic steroids, which has been endemic in sport in general, and is becoming more prevalent in women’s sport falls somewhat under this idea. The GDR women’s team in the 80’s were subject to severe steroid abuse and many were permanently masculinized in both physical and other senses.

Many were left infertile and at least one underwent sex re-assignment surgery. Even so, this is only related to sports involvement inasmuch as there is often an inextricable link between sports and steroid abuse. But the simple act of engaging in sport cannot masculinize a woman in any biologically plausible way.

Make no mistake, none of what the experts of the early 20th century wrote had any basis in fact or evidence for the most part. But in many cases, their fears did carry at least an element of truth, in the sense that these are issues that have come to light as women have entered sport in greater and greater numbers.

Absolutely none of which should be taken to suggest that women are unsuited for or too fragile for sport or should be excluded from or avoid it for any of the above reasons (real or imagined). Rather it brings up the simple fact that women and men differ in many important ways, including those that pertain to training, exercise and sports performance.

In some cases those differences are relatively small, in others they are relatively large. In at least some cases, women have concerns or face situations or concerns that men will never experience at all. And in many of those cases, the consequences can be absolutely devastating.

And this becomes a problem for a fundamentally different reasons related to the history of women in sport. Which is that, for the grand majority that sport has been played in the modern era, most of the athletes were male as were their coaches. Certainly this has changed in recent years and both continue and will continue to change but the reality is that most ideas about training, etc. come from work with men by men.

This is true in the realm of medical research as well, as I’ll discuss in the next chapter. The practical implication being that, in many cases, female athletes are being trained more or less identically to men. Which by definition means that women’s specific issues are not being taken into account or addressed. At best this simply leads to suboptimal results but, as discussed above, at worst it can lead to devastating physiological damage or permanent injury.

And that leads me into the next chapter and the remainder of this book, which will look at those differences and how they can, should or must be addressed.

Facebook Comments