Continuing on from yesterday’s discussion in Why the US Sucks at Olympic Lifting: OL’ing Part 3 where I first summarized the goal of OL’ing competition and then looked at the importance of body proportions, technique, flexibility, mobility, movement speed, fearlessness, feel, age and endurance I wan’t to continue today by looking at the often misunderstood roles of muscle mass and maximum versus explosive strength. Finally I’ll look at how some of these things have changed since the dropping of the press in 1972 in terms of their relative importance and focus among top competitors.

.

Table of Contents

Muscle Mass

At a first approximation, muscle mass would seem to be important to OL’ers and it is to some degree. First keep in mind that Olympic lifters compete within rigidly defined weight classes (though they tend to manipulate water to actually make weight). This tends to limit how much muscle mass can be carried within any weight class except for superheavyweight lifters who can be as big as they want (and as often as not the extra weight is blubber around the middle).

But within any of the fixed weight classes, lifters can only carry the amount of muscle for their frame and height within the realm of realistic body fat percentages and what they can dehydrate and still make their class. Mind you, that’s also true of powerlifters. But remember that powerlifters compete in three lifts: two lower body and one upper body. They have to have balanced musculature to compete in their sport because of the differences in the lifts.

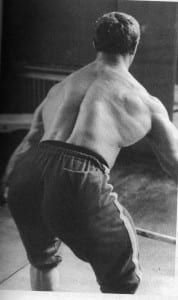

In contrast, the great majority of the power output in Olympic lifting is generated by the legs and back. The pull from the floor, even the drive for the jerk is done with the legs. Back extension is involved in the movement and you need the strength to keep the spine locked into position during a heavy pull. Olympic lifters often have back development that is just insane. The following picture comes from Tommy Kono’s book, sourced yesterday.

.

.

In contrast, having big arms isn’t really an advantage because if you’re using your biceps to lift the weight you’re doing the lifts wrong. Quite in fact, guys with big guns or big triceps often lose flexibility and have all kinds of trouble racking their cleans. The same goes for delts. Remember that the jerk is being driven overhead by the power of the legs before the lifter drives himself under the bar. You don’t necessarily need big delts for that.

But you say, what about triceps, those must be important to lock out the jerk or hold a snatch overhead. Yes and no. Think about how much easier it is to hold a heavy barbell in the bench press than if you bend your elbows even a little bit. That’s because with the arms locked, you’re in what’s called bone on bone contact. Your muscles aren’t working that much because your joints are taking most of the stress. But bend your elbows at all and you get crushed.

It’s the same reason that you could take a monster bar out of the squat rack (within reason) and not crumple so long as you didn’t bend your knees. Sure, your upper back might collapse and your lower back might round; but so long as you keep your legs locked, you won’t collapse immediately.

Same thing here, a snatch and jerk are caught on locked out elbows or it’s not a legal lift. And you can hold a hell of a lot of weight that way so long as you don’t let them bend (which red lights you anyhow). And even the push under in the jerk is accomplished, recall, by pushing the body (unweighted by lifting the feet up) under the bar more than it’s pushing the bar up. And gravity is helping pull the body down. So it doesn’t require much triceps strength. And certainly not triceps size.

And within a given weight class, carrying a bunch of muscle mass in muscle groups that aren’t really that relevant to the sport means less muscle in the groups that are relevant. It’s not like the powerlifter I mentioned above who needs muscular delts and tris (and even bis) for benching. For an OL’er, beach muscles are often wasted muscle (tho see below).

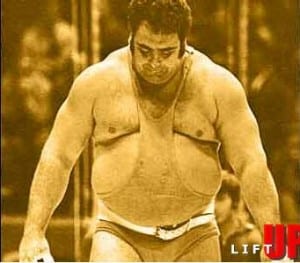

I’d simply point out here that the muscularity of lifters has gone back and forth over the years (but see my comments below) depending on the lifter, the country, the weight class and probably the drugs being used. Some are jacked, some are not; some barely look like athletes. Here’s Vasily Alexeev (one of the best superheavies to ever touch the bar) and the Pocket Hercules, Naim I Can’t Spell His Last Name.

.

Finally, due to the technical aspect of the sport, it’s not uncommon to see lifters, especially in certain weight classes, who appear to be relatively unmuscled (especially as matched up against similar weight individuals in other strength/power sports). Again, this isn’t universal but it does happen. Especially snatch specialists since the lift is speed and technique dominant.

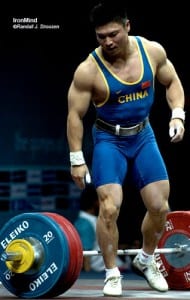

Even when lifters do have developed musculature, it is typically somewhat unbalanced due to the nature of the sport. Big legs are important, a big back is often seen. Big guns and delts, not so much. Though it’s worth noting that the Chinese Olympic lifters of late are just absolutely jacked and ripped. But this is a relatively recent development. But the Chinese weightlifting program actually does a lot of general bodybuilding work. Work that most Ol’ers have not traditionally done since the pressing era.

.

And really my point here is not that muscle mass is or isn’t relevant. Some lifters are jacked and some aren’t. Usually even when they are, the muscle groups developed tend to be a bit imbalanced. It’s the opposite of the typical gym light bulb, when they are heavily muscled OL’ers are usually all lower body and back with far less importance or size development (generally) in the delts and arms.

Relevant to this, in general the OL’s, especially as they are commonly trained really aren’t that great for developing msucle mass. At least not in an overall sense. In fact, most OL’ers who want to gain muscle mass do it with non-specific movements.

Leg size is built with squatting and front squatting, as noted above the Chinese do general bodybuilding movements (I’ll talk about training paradigms shortly). But just doing the OL’s doesn’t really build muscle mass well, especially not when trained for lots of sets of low reps (how almost everybody does it). Maybe in the upper back.

.

Maximum Strength

A common misconception is that OL’ing is about limit/maximum strength because, superficially it looks like other strength sports. And while strength is certainly a factor, it isn’t nearly as important as many think it is or are making it out to be (more accurately, it may be limiting for some but not for others and it’s certainly not universally true that driving up max strength will improve performance). And this really has to do with what the limiting factors in OL’ing performance are which is why I summarized it above.

And those limiting factors, that is the weak points that determine whether or not you make the lift are: how much weight you can throw into the air (high enough to get under it), how quickly you move under the bar (assuming it has enough bar height), whether or not you can fix it overhead (and this is a function more of stabilization and proper technique than anything) and whether or not you can then stand up with it.

In the snatch, leg strength is never limiting; if the bar is in position you can stand with it. In the clean and jerk, as I mentioned yesterday, certainly leg strength is a factor in the squat recovery. But having the bar in the right position, catching a bounce (an issue of timing, elasticity, etc.) is as if not more important than strength per se.

And even if a lifter does manage to grind to the top with a maximum front squat, they have less chance of making the jerk. Even when lifters push up squat strength, the focus is usually on their maximal ‘fast’ front squat (at the very least slow grinding squats are done rarely). Not how much they can move slowly. Here’s 200kgX5 by a Cuban lifter. Not that even the last rep doesn’t get particularly grindy. And you don’t see a lot of Ol’ers doing sets of 5 (the Cubans tend to use higher repetition ranges than other training systems).

And even of the above factors, the single limiting factor in the OL’s is this: throwing the bar high enough. Because if you don’t have the bar height in the first place, none of the rest of it matters anyhow since you can’t get under it. Let me clarify this, I’m not saying that there aren’t a dozen other factors involved here. Bar position, being able to hit the right positions, timing and a host of others contribute to whether or not a miss is made or lift. As Glenn Pendlay pointed out to me in feedback on this section.

To me, this seems simplistic. I think I would say, things like speed, the ability so sense and to hold the proper positions, a high RFD, the ability to switch muscles “on” or “off” quickly and at the appropriate time, proper timing, absolute strength, power, the proper ratios of strength between different muscle groups, and a “feel” for the bar.

.

Another way to look at it is could be power production, could be lack of strength of the correct muscle groups to allow you to hold the correct positions to allow you to apply power in the right direction, could be lack of timing, could be lack of limit strength, etc, etc, etc.

I don’t disagree, this is part of what makes the OL’s so complex, difficult and fascinating. The point I’m simply trying to make is that all of the above, while important, is still secondary to getting sufficient bar height. Because a lifter can have all of the above, proper positions, speed, RFD, etc.; if the bar doesn’t get thrown high enough none of it matters. I hope that makes sense.

So let’s assume for the moment that all of the above is in place, the lifter has perfect position, timing, etc. With that (poor) assumption, does maximum or limit strength (defined here roughly as 1 rep maximum) play much of a role in this singular aspect of the lift? Or put more differently, once you’re past a certain threshold of strength, will driving up that limit strength necessarily improve your ability to explosively move a weight in the power position? The answer according to most is no. Let’s look at why this is the case since it seems illogical.

First consider that there is often a fairly low correlation between slow speed maximum/limit strength and explosive power especially once maximum strength gets beyond a certain point. Again, you need some threshold level of strength but once you get beyond a certain point, just getting stronger and stronger tends not to do much good or improve performance in explosive movements. In fact, it may even hurt (see below).

This is just a function of the whole rate of force development (RFD) issue which I must now explain. Most limit strength movements take a relatively long term (at least relative to most sporting movements) to occur. Perhaps it’s better to phrase is that they don’t tend to occur quickly (think about the duration of a maximum deadlift, squat or bench press). That is, lifters have quite a bit of time to generate maximum force in those types of lifts and they may end up generating almost a quasi-isometric during the sticking point which they can hopefully grind through.

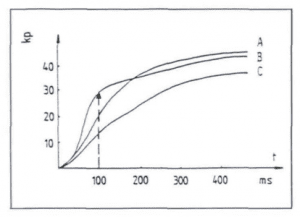

In contrast, almost all explosive movements in sports isually take place in 0.1-0.2 seconds or less. Because while the Ol’s themselves do take longer (a full snatch may take a full second if you count first and second pull along with the catch), the explosive phase per se is in that time range, about 0.2 seconds or so.

And simply, if the athlete can’t generate force in that time period, it’s not relevant to success because it can’t be utilized. The only force that matters is that which can be generated nearly instantaneously. Even in speed skating with it’s odd 1 second glide on one leg, the actual push part takes place in 0.2 seconds or so (the other 0.8 seconds is sitting on that leg wondering where your life went wrong). That’s where most sports live in terms of how much time the athlete has to generate maximum force.

This graphic shows what I’m talking about. Because although athlete A is physically stronger (if given half a second to generate force), athlete B will actually outperform him in any movement lasting 200ms or less. Because at the 100ms mark he’s actually generating more force because he can do it faster.

.

In fact, work by a researcher named Tidow (published in 1990 a paper titled “Aspects of Strength Training in Athletics” in New Studies in Athletics) has even found a negative correlation between maximum strength and movement speed. That is, the stronger someone gets (beyond a certain point), the LESS explosive they are. And certainly in most explosive sports (throws, etc.) in the modern era, there has been a far lower emphasis on maximum strength than in previous years.

Even in sprinting you simply don’t see the focus on maximum strength; no more 600 pound half squats as in the era of Ben Johnson. It’s more like double bodyweight and that’s more than enough. Rather, the focus is on technique, speed of movement and being ‘as strong as needed’ but no stronger.

Of course, in the throws, the weight of the implements is much lighter than in the OL’s and certainly one would expect the amount of maximum strength needed to be higher. But keep in mind the nature of the lifts and the determining factor in success which is how much weight can be thrown into the air and then caught (either on the chest in the clean or overhead in the snatch and jerk).

That is, how much weight you can haul to the power position is not relevant if you can’t throw it high enough to get under it for the catch; certainly how much you can haul to that position slowly is of fairly little relevance (many OL coaches make sure that even accessory work is only done if bar speed stays high).

A deadlift stops (and is deccelerating) when the OL’s really start (and the goal is acceleration) and strength in that movement beyond a certain point has no real impact on how much can be thrown during the third pull (since the limiting factor is what you can throw, what you can get off the floor is, by definition, not limiting).

Similarly, the jerk is not a press. In the jerk the power is being generated by leg drive and only very secondarily by arm drive (again mostly to push the lifter under the bar). Even the push press relies far more on arm drive than the jerk ever will (the Soviets felt that excess push press work could actually harm the jerk by teaching the lifter to drive with the arms excessively).

Finally, all of the squat strength in the world is only relevant if you can pull the weight to the catch position in the first place. Certainly you need enough to recover the front squat but, as I discussed when I talked about technique, all of that strength doesn’t matter if the bar is out of position in the first place and lifters with amazing technique often get by with only marginally higher front squat numbers than their best clean. You can front squat the world but if it lands too far in front of you, you’re not standing up with it.

The point being that, yes, maximum strength is part of OL’ing. But beyond a certain point it’s not only not beneficial to keep driving it up (as many OL’ers find out the hard way; they’ll spend months driving up their maximums in accessory work and find that their competition lifts haven’t budged) but can be detrimental. Either by causing a reduction in movement speed or simply by causing the lifter to put excessive time, energy and recuperative ability into something that isn’t the competition lifts.

.

Explosive Strength

And basically following from the above discussion, it should be clear that while limit/maximum strength has, at most, a limited role for sucess or failure in the OL’s, explosive strength is the absolute key to the sport. And this is reflected in the modern training of Olympic lifters. The OL’s are inherently explosive/accelerative due to the fact that the bar is thrown. Contrast this to a movement like the squat or bench press which start and finish at zero velocity and there is actaully a decceleration phase at the end of the movement (unless you add chains or bands); in the OL’s you can, do and must accelerate all the way through the movement.

And this is reflected in the training of OL’ers. All movements from the OL’s to themselves to assistance movements such as squats, pulls or good mornings are done in an explosive fashion since this not only mimicks how the OL’s themselves are done but gives the best transfer/carryover.

Again, other movements are done similarly and arguably the greatest OL’ing coach in the history of the sport actually defines a maximum squat as the maximum that can be lifted rapidly; his guys could lift more if they went slowly but he doesn’t allow it because it’s not relevant to the sport.

Simply, slow grinding movements aren’t generally terribly relevant for the reasons I discussed above in the section on maximum strength because no aspect of the lift is or will be grinded (unlike powerlifting or strongman). Rather, it’s the force that a lifter can generate rapidly that is relevant to success or failure in the lifts. And that explosive strength is usually trained in a specific fashion, focusing on acceleration above all and only using weights that not only can be accelerated well but also mimick the OL’s in terms of mechanics, bar position, etc.

.

Pre-1972 vs. Post-1972 Olympic Lifting

To close it out today I want to make some comments about changes in some of what I talked about above in the pre-1972 vs. post-1972 eras of Olympic lifting. Keep in mind that 1972 was the year that the press was dropped and the sport moved to only the two ‘quick’ lifts: the snatch and clean and jerk.

Remember that the clean and press was a strength lift. It required more muscular development in the delts and triceps/arms along with more limit strength because it was a lift that could be ground through (unlike the other two lifts). When the press was dropped in 1972, that requirement was eliminated. Initially, it was thought that lifters would become much leaner and lighter since they would no longer have the requirement for what was seen as ‘unnecessary’ upper body muscle mass anymore.

And that certainly did happen to at least some degree especially in the earlier days of the sport. As I mentioned above, the muscularity of lifters is highly variable; too much so to make any particularly broad generalizations about it. It’s probably safe to say that a need for big delts and arms was minimized in the post-1972 era of the sport even if some lifters still like to build them (so long as it doesn’t impact on their ability to catch a clean or make weight). Dudes like big guns and that’s never gonna change.

I’d mention that a focus on optimizing technique in the lifts was really taking place around this time as the Eastern Europeans really put a lot of energy into analyzing the best way to lift a weight. And without taking anything away from the early athletes in the sport, the simple fact is that technique was not fantastic prior to the 60’s and 70’s.

This was true of most sports (again see my comments about speed skating in the era before indoor ovals and optimized technique); technique and implements were less well developed and many strength and power athletes just made up for it with brutal strength (i.e. Ben Johnson had a claimed 600 lb half squat and throwers often did 800 lb 1/4 squats which is about double of what anybody today would bother with).

To say that technique was rough in the early days of the sport is an understatement. And since the technique wasn’t there, they had to compensate by just being brutally strong. Paul Anderson is a good example; his technique in the lifts was at best mediocre. But he made up with it through such sheer brute strength that it just didn’t matter. Were guys of this era strong? Yes. Was their technique pretty? Not so much.

But as technique was being refined and figured, training started to change with a focus moving towards becoming technically proficient (and efficient) more than just muscling the weight. This was about the time that Abadjaev was cutting out assistance movements (most of which were meant to build strength or power in specific positions) and focusing on increasing training frequency (with near maximal weights as technique in the OL’s changes when you move from lower to higher intensities).

Everyone soon followed and high training frequencies in the competition lifts became the norm. This is true for both lifts but especially the snatch; technique is so sensitive there that lifters who go a day or two often lose their groove. Mind you this was only possible in systems where the athletes were paid to be full-time athletes (and have pretty strong incentives to the same stuff day after day). Unless you could train 2-3 times per day, you couldn’t do this.

In that vein, it’s not unheard of to hear of top powerlifters or strongmen who only train a given lift (or even the competition lifts) once per week. It’s still workable even if most are going to higher frequencies of competition lifting. But it does work. This simply doesn’t cut the mustard in OL’ing and it would be almost unheard of for any top Olympic lifter to not train the competition movements (in at least some fashion) on a near daily basis. Which, mind you, is facilitated by the go/no go nature of the lifts and the fact that they don’t grind the body down quite as hard as maximum PL’s.

Sources

Essential Components Weightlifting Technique: Part IV While his site is awful (old style frames), Charniga has done a tremendous amount of writing on the OL’s. In this article he looks at the idea of just jacking up maximal strength in the OL’s to raise competition results and why that approach is flawed.

Again thanks to Glenn Pendlay and others for their input on this and other parts of this series.

And having completed a look at the components necessary for weightlifting performance. Tomorrow I’ll start looking issues of physiology and genetics and finally address who’s the best.

Read Why the US Sucks at Olympic Lifting: OL’ing Part 5.

Facebook Comments