In Why the US Sucks at Olympic Lifting: Olympic Lifting Part 2, I gave a primer on the technique of Olympic lifting looking only at the snatch, clean and jerk. Continuing in that vein I want to now look at what physiological factors go into successful OL’ing performance as that will lead into the logical discussion of genetics, who’s the best and all the rest. To save it being too long, I’m going to split this into two parts. First a brief summary of the last two days.

Table of Contents

Summarizing Olympic Lifting

Lifters compete in two lifts, the snatch and clean and jerk (the press having been dropping in 1972); lifters get three chances for each lift and the goal is to lift the most weight a single time with the lifter’s total for each lift (only successful lifts are counted) determining the winner. In general, depending on the dynamics of the event, lifters have at a minimum 2 minutes between lifts (only in the situation where they follow themselves); in most situations they will have longer than that.

Recall from my discussion yesterday the basic nature of the lifts which is to throw a weight explosively so that it can be caught either overhead (the snatch), on the shoulders (clean) or overhead (the jerk). Which means that the critical part of the movement (the ‘weakest link’ so to speak) is how much weight can be thrown to a minimum required height for a legal catch. That will determine how much is successfully lifted and everything else only contributes inasmuch as it contributes to that part of the movement. Because none of the rest of the movement is relevant if you can’t get the bar high enough in the first place.

Even there, the snatch and clean and jerk differ. Because the weights are lighter (again, 20% on average) in the snatch, it’s far more of a speed/explosion/technical lift. The clean and jerk, relatively speaking, is more of a strength lift. Even there, how much you can clean is based on how much weight you can throw into the air (and whether or not you can then get under it, get control of it, stand up with it, and then put it overhead).

In that vein, I’d mention that it is not uncommon for a lifter to be relatively better at cleaning than jerking or vice versa; since the lift is determined by what you can do for the combined movement, this has the end result of letting the ‘weaker’ of the two lifts determining the maximum weight used.

Put differently, a lifter can be a monster jerker, just strong as the world overhead. But if they can’t clean nor stand up with the weight, it won’t matter because they never get to show off their jerk abilities. By the same token, a lifter who can clean the world but can’t jerk to save their lives will be limited by the jerk unless they enter one of the many power clean competitions that are being held in recent years.

And while I really don’t want to get deeply into gender differences, this is often more common in female lifters due to the difference in lower body vs. upper body strength. Many women can pull to the shoulders in the clean far more than they can get or support overhead. Women often need more direct upper body work for this reason and it’s interesting that the Chinese women had JACKED upper bodies and were stable as hell overhead in Beijing.

I’d also remind readers that the time between when the bar is thrown into the air and the lifter catches it is not long (find out time), a split second. The ability to throw the bar up and then rapidly reverse and effectively ‘jump’ or ‘dive’ under the bar and do so before the bar falls too far.

Movement speed and reaction time is also critical following the explosive ‘throw’ of the bar; the lifter has to be able to switch rapidly from throwing the bar up to moving underneath it while continuing to exert force upwards on the bar. And again, the majority of force production comes from the lower body and back. Other muscles are involved in accessory roles but those are the key groups.

So what physiological characteristics does all of the above require?

.

Height/Body Proportions

First let’s look at body proportions since they are crucial here and a huge part of selection for Olympic lifting success. You might remember how I mentioned way back when that, among other reasons, one of the reasons China dominated OL’ing is that shorter limb lengths tend to confer an advantage. This is just a physics thing, longer levers take longer to move through space and top Ol’ers are often found to have very similarly related body proportions in terms of femur length, torso length, etc.

Taller lifters also have way further to move to get from full extension to the squat under which puts them at a disadvantage compared to shorter guys; as any tall squatter knows it’s also more difficult to get stand up from the full squat position due to the long lever arm generated by the length of the leg. Which isn’t to say that there haven’t been top lifters without those proportions. They exist but they are in the minority. Here’s one of them, Ivan Chakarov as an example of a highly successful but relatively taller lifter.

Body type/proportions is also relevant because the technique in the OL’s are less able to be changed compared to something like powerlifting. A tall powerlifter can alter his squat stance, widening it, or his deadlift stance (perhaps pulling sumo) to compensate for poor levers or what have you. He can alter his bench technique, change his flare, his arch, where he brings the bar, to adjust for levers that may not be optimal.

The Ol’s are far less able to be modified by this due to the exacting technical nature of them. You can make small adjustments in things like stance width or grip width but the specifics of the sport don’t allow for much variation. You can’t pull a clean sumo to compensate for a long torso is what I’m saying. So the body types that are set up for optimal performance of the lifts is far more limited compared to the other strength sports.

Mind you, this is at least one thing that many of the Eastern European countries with their heavy early selection and testing were looking at. They knew what types of mechanics were best for certain sports and athletes were put into sports where they were most likely to succeed based on physiological characteristics (and predictions on what a kid with certain proportions would grow up to be physically).

I’d note that body proportions aren’t something we can do anything about, I mention it only because it can be a determining aspect of optimal performance. Yet another reason you need numbers going into the sport, you not only have to deal with all of the other factors I’ll discuss today and tomorrow but also have that lifter have the right body proportions in the first place.

I’d mention that another body related factor is joint robustness. The catch on the clean and snatch exert a big force and knees, wrists and elbows can often get beat up (elbow dislocations are not unheard of in the jerk) by the pounding of catching heavy weights. Just another factor that needs to be in place for someone to be a successful as an OL’er. It’s not something that you can massively control although progressive controlled loading over time does tend to strengthen joints and connective tissues.

So now let’s look at factors which are actually modifiable through training more or less from unimportant to massively important.

.

Technique, Technique, Technique

In modern Olympic lifting, perhaps no single factor is more important than good technique. This is actually true of most modern sports, where improvements in technique (and often the implements used in sport) along with the requirements for absolutely perfect technique is usually paramount for success. And in many sports have far outstripped issues of conditioning or what have you.

Mind you, this can actually vary across sports and I’d offer that certain sports are relatively less sensitive to poor technique than others. Usually these are endurance events (where you can make up for a deficit in technique with grinding amounts of work); more to the point they are typically in activities that bear some resemblance to normal human movement patterns.

Running and cycling are two examples. They both involve basic human movement patterns (combined hip, knee and ankle extension as occurs in normal human walking) with cycling simply being modified with gears. And it’s not uncommon to see even top tier athletes with relatively poor technique that they compensate for with just enormous amounts of training. Conditioning can overcome poor technique even at the highest levels in these types of sports.

But as you start moving further away from movements that are fairly ‘standard’ to humans, such as swimming or rowing, you start getting into a realm where conditioning really can’t make up for a lack of technique. As I discussed previously, swimming is monstrously technical and folks aren’t even entirely sure how humans swim. Good technique is critical and without it the most well-trained aerobic beast will just spin in the water.

Speed skating is similar in this vein, completely divorced from normal human movement patterns (it’s hip extension but to the side in hip flexion with a rounded back) it’s a sport where technique really can’t be overcome with strength or conditioning. A technically proficient swimmer or skater will beat a well-conditioned one any time (a technically proficient AND well-conditioned athlete will beat both of them of course) and you often see little kids with good technique dusting adults who are stronger and fitter.

Which is part of why I wanted to discuss those two specific sports in this series, in addition to the other reasons. Because, even among the other strength/power sports, OL’ing is a hell of a lot more like swimming or speed skating than it is like powerlifting or strongman.

Because in OL’ing, all of the strength, power, explosiveness in the world really doesn’t pay the bills if the technique is lacking (again moreso in the snatch than in the clean and jerk but it’s crucial to both). Especially in the modern era (note my comments about how skating 3 decades ago was less technical and more conditioning based; swimming has seen similar evolutions in the modern era) which I’ll come back when I wrap up today.

Even in powerlifting, it’s not uncommon for lifters to overcome technical weaknesses by simply getting strong as all fuck. As well, a powerlift that is slightly out of position can often be muscled back into position. That’s on top of a lot of different techniques being workable to achieve the goal. Even in strongman competition, brute force strength can often overcome technique to at least some degree. And, no, I’m not saying technique doesn’t matter in these sports; it’s just a matter of degrees and what you can get away with (amusingly you can get away with a lot more in outdoor inline speed skating than on the ice).

In OL, neither is really the case. Technique in OL doesn’t vary that much beyond some small differences (usually having to do with individual differences in body mechanics or whatever) and the go/no go nature of it makes getting a missed lift back into position nearly impossible unless the deviation is very small.

That is to say, a squat can be saved if the lifter gets out of position. A snatch can’t. Technique in the OL’s is just at another level of importance to the other strength/power sports. And don’t misread what I’m saying here, I’m not saying that technique in the PL’s or strongman is irrelevant, that would be stupid. But relatively speaking, technique (or the lack thereof) can be overcome with sheer brute force strength in those sports. In OL’ing, it really can’t. Certainly not in the modern era of the sport and most specifically not in the snatch.

And as I hope to have gotten across yesterday, it’s not as if the technique of OL’ing is terribly natural. Because while the basics can be taught in a short period of time, the details, the nuances, the rest of it can take years of grinding practice. It’s not like some other movements which, again relatively speaking, can be learned and mastered relatively quickly.

Again, without taking anything away from powerlifters, the fact is that bench pressing is a pretty trivial movement compared to a snatch. You can teach the first to basic competency in a few hours or weeks at most (I realize that mastering GEAR is a totally different issue, I’m talking about a basic raw bench press). Mastering the snatch can take a lifetime (har har) and even there a lifter having an off day will find themselves unable to snatch anywhere close to their best weights. Their timing is off, their bar path is a hair off and suddenly they can’t do jack crap in the lift.

.

Flexibility/Mobility

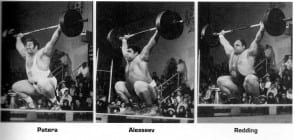

Flexibliity and mobility are also of prime importance in the lifts for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is having the ability to get into a deep squat position and maintain control of a heavy bar as it comes down on you and you resist gravity. I mentioned previously that as lifters made the switch from the split versions of the lifts to the squat versions, many older lifters had a great deal of difficulty adapting, they simply weren’t able to develop the mobility needed later in life to do a good squat clean. In the snatch, shoulder mobility is key for a proper bar path and catch. Lifters without sufficient mobility or flexibliity often find themselves having great difficulty in various aspects of the lift. The following picture, again from Tommy Kono’s book shows the difference in mobility between Ken Patera (a top US lifter of the day) and two European lifts.

.

The picture isn’t as big as I would have liked (click it for a larger version) but you can hopefully see that Patera’s bottom position in the snatch isn’t as low as the other two lifters. Simply, he lacks the mobility to hit a true deep squat.

.

Movement Speed/Fearlessness

I mentioned both of these yesterday but I want to reiterate them. The ability to move quickly under the bar is another key to lift success. How much of this can be trained and how much is inherent to the lifter I can’t really say but it is key. Because no matter how high the bar is pulled, if the lifter can’t get under it quickly enough, the lift will still be lost.

Related to this is the fearlessness aspect of the OL’s, diving under a heavy bar that is literally falling down on top of you. Many lifters balk or hesitate when it gets heavy (another reason to train with high loads consistently to get practice going under heavy bars) and that hesitation either results in a missed lift or worse. Being able to commit 100% to throwing the bar and then getting under it is key to success.

Again, much of this is a practice issue but it points out the benefits of starting young in the sport. Little kids don’t have the same level of fear when they learn stuff like this (gymnastics is identical in this regard) and by the time the weights get scary heavy they are used to it. Adults learning the lifts can take years to get to where they will commit to the lift 100%.

.

Feel

There is another aspect of the OL’s, this is yet another reason I brought up swimming and speed skating in previous parts of the series. And it can only be described as feel. In swimming and on the ice it’s water and ice feel, feeling how you’re applying pressure to the medium to get the most out of it. In OL’ing, I’m not sure what it is exactly: feeling where the bar is, making minor adjustements, feeling the flex of the bar, the whip of the plates. The things that make that final difference in lifting ability.

This sounds like voodoo and probably is, it’s ephemeral and in all three sports it’s something that can’t be taught; it can only be learned. Some seem to have it naturally, some learn it after some period of time, some never learn it. It’s impossible to describe but you can watch two athletes in these sports who otherwise have identical technique and conditioning and one just ‘looks’ different. You can’t exactly say what the difference is but it’s there. Since I was doing so bad a job of describing this, I asked Glenn Pendlay if he could describe it. With his permission, here’s what he said:

It really is funny how some people can seemingly have it all. big squat, can jump high and run fast, flexible, just strong and athletic. And yet when you watch them lift, you can tell it just isn’t clicking for them. I mean even if they are technically correct, good line of pull, correct positions. But “it” just isn’t there and its almost impossible to quite put your finger on what you are talking about but you can just see it. And they can even lift pretty good weights, but still you can just see that something is missing.

.

And then you have other people who just right from the start just get it. And you’re right, its not technique that I am talking about. I almost want to call it timing or rhythm, and that’s part of it but doesn’t really describe it either. And some people who don’t just have it from the start develop it, and some never do.

Again, it can’t be taught, it can only be learned. Hell, it can barely be described. But it exists. Ok, moving on, let’s look at other factors of interest to OL performance.

.

Age

A factor that I haven’t really discussed anywhere in this series is that of age on performance. And without going into excessive detail, it’s a simple fact that most top performers in the sport start fairly young. This isn’t universal and there are exceptions (Ben Johnson, for example, started relatively late for a track athlete; he was in his teens).

But when you consider that mastering technique in complex movements can take upwards of 10 years or 10,000 hours (on average), that has some clear implications for technique heavy sports (such as swimming, speed skating and OL’ing). Especially when you consider the realities of when strength/power athletes tend to hit their peak which is typically in the early to mid 20’s (note endurance athletes often hit their peak later in life, in their late 20 or early 30’s but we’re talking here about strength/power production).

At the very latest, assuming a roughly 10 year period of learning, you’re looking at starting no later than age 14 or so to have a chance of reaching your potential by the time your strength/power output peaks. Not that it can’t be done in shorter periods, mind you, just talking averages. From a technical standpoint, from a joint robustness standpoint, from a fearlessness standpoint from a feel standpoint, the more time a lifter can put under the bar before hitting their peak (around their mid 20’s) the better.

And as I pointed out when I talked about China, in the modern era, most start earlier than that. A typical Chinese Ol’er has put 10 years under the bar by the time they are about to hit puberty. A lifter starting in their teens or later is simply at a nearly unassailable disadvantage compared to that.

.

Endurance/Fitness

Endurance per se is of absolutely minimal importance to OL’ing, in this sense it is like some of the other pure strength/power sports like the throws in track and field or powerlifting (modern strongman events have a fairly high endurance component oddly enough). Reportedly many European OL’ers are chain smokers which should tell you just how irrelevant endurance is to this sport.

The lifts last a second or two at most with most of the real action happening in a tenth or two during the explode phase. It’s pure ATP/CP. And in competition there are only three attempts taken for 6 total lifts (with warm-ups). And unlike powerlifting meets which often take 8 hours to complete, OL meets move quickly and are over pretty fast so you don’t get exhausted just sitting around being bored.

I’d note that this may have been subtly more important back when all three lifts were contested, just because more had to be done both in training and competition. But even there it was only 9 lifts in competition and there was overlap between the clean and press and clean and jerk.

The only real endurance needed is for when a lifter follows themselves which means they have two minutes but that’s more than enough time for ATP/CP to be replenished after a missed lift. This is especially true given the go/no go nature of the lifts. In powerlifting, a missed lift where the lifter gets stuck in the middle can grind down the nervous system and require 5-10 minutes recovery. A missed lift in OL’ing does no such thing because even if a lifter misses the squat recovery, either he tries once or twice and gives up or he bounces back up.

The type of fatigue (especially CNS fatigue) seen in grindy lifts isn’t seen in the OL’s. You see this in the training of Ol’ers which I’ll talk about shortly. They generally take far shorter rests than powerlifters because of the nature of their lifts. So while a powerlifter might take 5-10 minutes between maximum lifts, an Ol’er might take 1-3 minutes. Quite in fact, many lifters find that they lose their OL’ing groove if they rest too LONG between reps (especially in the snatch).

About the only even remote component of OL’ing that might be related to endurance is really better defined as work capacity. Training in the modern era for the sport is based around either a lot of volume or a lot of frequency or both. Lifters have to develop the capacity to handle the training loads required to reach the highest levels; along with being able to recover quickly enough to do it again later in the day. This is simply built over years of progressively and gradually increasing training volume, intensity, frequency or all three.

Sources

The Sport of Olympic Weightlifting: Training for the Connoisseur by Carl Miller. An otherwise forgettable (and slightly goofy) book, this has a good discussion of optimal body dimensions (and how technique can be altered) for Ol’ing.

I’d also refer everyone to yesterday’s part for book sources which talk about all of the above to one degree or another.

And that’s where I’ll cut it today. Tomorrow I’ll look at issues of muscle mass, maximum and explosive strength and finish by looking at how some of the above has changed from Pre-1972 to Post-1972 Olympic lifting all as a lead in for Friday’s examination of who’s the best and how the US has done both recently and historically in the sport.

Read Why the US Sucks at Olympic Lifting: OL’ing Part 4.

Facebook Comments