In the past (insert stupid number) of parts of this series I’ve looked at a ton of different sports systems to see if there are commonalities, finishing with the bizarre situation in US Speedskating last time. And certainly there often are. Kenyan running, UK track cycling, the former Soviet Union, the GDR, Bulgaria, Australian swimming, the Chinese sports machine. All had their own approach to the ‘problem’ but approached it or got there in roughly similar ways.In the majority of cases, a combination of large numbers of athletes, access to the sport, incentives of some sort, support, coaching (and often drugs) were part and parcel of consistent sporting success.

This was even true for America which despite its completely decentralized (and often screwed up) approach to sport is often successful or outright dominant, at least in certain types of sports. There I looked at too much background in terms of geography, culture, economics, etc. all as background for discussing the Big Three sports: football, baseball and basketball. Of those three, only basketball has been consistently contested at the highest levels. And there America is simply dominant beyond description.

The main point of discussing those three was not only to show how a decentralized system can still produce but also to point out how those three sports have so massively impacted on other sports in this country. Their huge incentives and the rest are a monstrous draw for the people who go into sports (for financial reasons especially) and that generally means our large underclass. Meaning, as often as not, minorities. Who, as often as not, are physiologically wired to succeed at certain types of sports.

From there I moved to track and field, a non-professional sport that we are also utterly successful in and have been consistently since the early part of the 20th century. As much as anything some of that seems to be related to ‘overflow’ from the big three. With a massive high-school and collegiate tradition (meaning, if nothing else, incentives in the form of education), athletes who don’t go into the Big Three still have an outlet. The monstrous number of events and potential physiologies that can be accommodated allow that many more to potentially succeed. Subjected to the insane collegiate competition schedule, thy are honed to an edge and go to the Olympics to kick ass.

Then I looked at swimming, the first ‘exception’ to all of the above. It’s a sport pursued historically and predominantly by middle and upper-class whites (and only recently by minorities at all), a group that rarely competes for explicit financial or even educational reasons. They have money and seem to come from a strong internal drive/desire for individual competition. They also go into the collegiate system but there they often choose schools based on the swimming program rather than education per se.

That led into a discussion of cycling in the US, a sport that has always been fairly niche with small numbers; again pursued primarily by middle or upper class whites. And where, for reasons primarily dictated by geography, we had talent but it wasn’t prepared to succeed in the competitive professional European ranks, at least not until recently. Mainly it was an illustration of how a sport can change in America; more specifically, how a specific individual (Lance Armstrong) was able to make America care about a sport singlehandedly.

I finished up by looking at the oddest exception of all, US Speedskating. Contributing the largest number of American winter Olympic medals, we also are (barely) at the top of the leader board. It’s an exceedingly niche sport with a tiny number of skaters, no access, no coaching, an incompetent federation and no incentives.

It seems to contradict everything that came before it although the specifics of the situation (the small Minnesota/Wisconsin area) may make it more similar to the other systems that it first seemed. As much as anything it was to show that a sport can often succeed in spite of itself; I also wanted to show how a sport can manage to kill itself off as our success in the sport seems to be on the wane.

And with all of that finally out of the way I can look at Olympic lifting and will look at nothing else. I’ll be looking at the same basic set of issues mainly to look at the sport in the US, both historically and in the modern era. Part of the reason (besides being a wordy bastard) that I spent so much time on all of the background was that I see elements of each in the situation of OL’ing.

Which was the point of this nonsense from the outset, to show that the problems with Olympic lifting in this country are not simple (i.e. need more money, need more strength). Nor are the solutions simple, assuming they even exist. All of this and more I will look out as this series marches on. And I’m restarting the series count with 1 so it doesn’t get too stupid.

Once again, I’ll start from the beginning. I can’t assume that everyone reading this has a background in Olympic lifting, hell I can’t assume that anybody but me is still reading this at all. But I’m going to cover some basics of the sport, competition, technique first just as background for the rest of it. So, let’s go all the way back to the beginning

.

Table of Contents

A Very Brief History of Olympic Weightlifting

Since men started competing for fun (as I detailed previously), it’s likely that one thing that people sought to determine was who’s strongest. It’s simply a function of competition and proximity bias. Fast people want to see who’s fastest, endurance people who can go the furthest. And big strong men want to know who’s the biggest and strongest. And that entails lifting heavy things. This tradition can be found in almost all cultures and still exists in many sports in varying guises. The stones of strongman, various events in Highland games, etc.

Of course, at some point in the game, folks figured out that metal could be made into shapes and that made it a bit easier to lift than the strangely shaped rock down the road. And weightlifting in some form or another was invented. That would give way to barbells which would logically lead to folks doing the same sort of thing, seeing who could lift the biggest or heaviest weight.

According to my primary source (see below), the first competition in Olympic lifting were contested in the late 19th century with the first champion crowned in 1891. At the time there were no weight classes, whomever lifted the most was the strongest. It was competition at its most basic. And the lifts contested early on weren’t what we typically think of when we think of Olympic weightlifting.

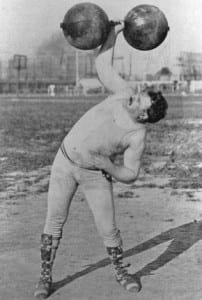

For example, here is one of the two lifts contested at the 1904 Olympic games called the all-around dumbbell lift (the other lift was the two-hand lift. A grand total of 4 lifters from 2 countries competed: three Americans and one Greek. The three Americans swept the all-around dumbbell lift medals (the Greek guy didn’t enter) but the Greek took gold in the two-hand lift.

I’d note that much of the interest in weightlifting came out of the physical culture movement of the late 19th and early 20th century, this involved not only exercise but also health, nutrition and other issues. For a particularly strange look at this particularly strange time, see the documentary The Road to Wellville.

The sport would continue to evolve and become an official Olympic sport by 1920. By 1932 there were 5 weight classes and the sport was made up of three lifts: the overhead press, the clean and jerk and the snatch. All three lifts representing different ways of getting a weight overhead. It was still just called weightlifting though; I imagine “Putting crap overhead” lifting just didn’t have the same ring to it.

But I wonder, semi-seriously, if there isn’t some innate evolutionary drive to wanting to put stuff overhead. Something about holding something overhead triumphantly to show that you owned. Like this.

Throughout the first 40 some odd years of competition, the three lifts would be contested with the results being based on the heaviest weight lifted in each of the three; the lifter who totalled the most weight (i.e. had the highest sum of each of their best lifts) was the overall winner although you could also win individual events.

It’s important to realize that the press would be dropped from competition in 1972 (and keep this date at least roughly in mind as we go forwards) due to some severe problems with judging the lift (the lift had become almost a standing bench press due to the allowance of layback). From that point on, the sport of Olympic weighlifting would be contested only with the snatch and clean and jerk and this change caused a fundamental change in the nature of the sport that I’ll address in detail later. Let’s look briefly at each of the three lifts (I’ll address technique tomorrow).

.

The Press

In the press, after cleaning the weight (pulling it from the floor to the shoulders), the weight was pressed overhead to lockout with no prior knee bend. Note the layback in the following video of Serge Reding doing a 228kg (502 lb) clean and press; it was problems with the layback and judging what a press was that led to it’s eventually being dropped from the sport.

As I mentioned above, the press was dropped from competition officially in 1972 and this had a number of consequences for the sport that I’ll mention eventually (and I will be doing some jumping back and forth from the pre-1972 to post-1972 era for reasons you’ll see).

In the modern era, discussion of the Olympic lifts centers around the other two lifts: the snatch and clean and jerk. From a practical standpoint, there might as well have been two separate sports of Olympic lifting: pre-1972 OL’ing (with the three lifts) and post-1972 OL’ing (with only the two). Again, keep that year in the back of your mind.

While the press was really a strength move, the snatch and clean and jerk are more explosive. And they share a similar characteristic in that, after the bar is lifted from the floor to what is termed the power or ‘explode’ position the bar is literally thrown into the air while the lifter moves underneath it which I’ll look at tomorrow when I overview technique.

All that really differs between the lifts (and you can actually think of the modern sport as three lifts: the snatch, the clean and the jerk where the jerk simply follows the clean) is where the bar ends up after the lifter throws it into the air (and then moves underneath it).

.

The Snatch

In the snatch, the weight is lifted in a single motion from floor to overhead at arms length (the arms must be locked for the lift to be legal). Effectively it is ‘snatched’ overhead. This requires that the bar be thrown high enough for the lifter to move underneath it with locked out arms. Since the bar has to go higher to achieve lockout, the weights lifted in the snatch are typically about 20% lower than in the clean and jerk. To illustrate this movement, here is a video of the great Greek lifter Pyrros Dimas performing the snatch.

In addition to generating lots of infantile giggling when you mention it, the snatch is considered one of, if not the, hardest activities in sport. The movement happens in a fraction of a second and the slightest error in technique can cause the weight to be lost in front or in back even if it’s high enough to get under it. That’s assuming you can generate enough power to throw the weight high enough in the first place.

Despite the lighter weights, the snatch requires/generates the higher power outputs of any lifting movement (far more than the technically incorrectly named ‘powerlifting’). For this reason, many strength coaches use the snatch (or some derivative movement such as the power snatch, with the bar being caught in a half or partial squat) for this reason; to train athletes to generate high power outputs.

.

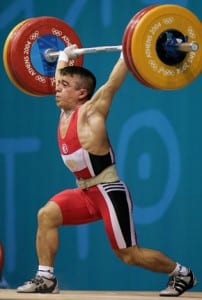

The Clean and Jerk

The clean and jerk is actually two movements that, for many purposes, can be considered separately; they are only considered a single lift in that you do the jerk after the clean. The clean is similar to the snatch in that the bar starts on the floor and is lifted into the power position before being thrown as the lifter moves under it. The difference is that the bar is caught on the shoulders. Since the bar needn’t go as high, this allows more weight to be lifted. Again, about 20% more than the snatch on average (and at least one lighter lifter has done a triple bodyweight clean).

After standing up with the weight, the lifter then dips (performs a slight knee bend) prior to throwing the bar overhead (the jerk) and moving underneath it with locked arms (the ‘jerk’). A key aspect of the jerk, separating it from the press, is that the jerk happens nearly instantaneously. The bar isn’t pressed out but rather thrown overhead as the lifter goes underneath it. In fact, pressing the bar out will get the lift disqualified depending on the strictness of the judging. The elbows have to lock immediately and here’s a video of a clean and jerk.

.

For completeness, I’d mention that there are technically three ways of jerking the weight although the split jerk shown above is by far the most commonly used. Some lifters power jerk where the feet are not split and the bar is caught overhead in a partial squat; the feet stay side by side. As well, a small minority of lifters perform a squat jerk where, after the bar is thrown upwards, they squat all the way down to catch the bar. When successful, it’s amazing to watch. It’s also very easy to lose the lift. Because it’s more stable because of a larger base of support, the split jerk is used by the majority of lifters. The three types of jerks are shown below.

.

Squat vs. Split Technique

You might notice that the videos of the snatch and clean and jerk show the lifters catching the bar (either on shoulders or overhead) in a full squat position sometimes called the squat snatch or squat clean. I bring this up as it was not always the case. In the earliest days of the sport, most caught their cleans or snatches in a split position as shown in the next video. This was called the split snatch (har har har) or the split clean.

It was somewhere around the 1950’s or so that the big transition from split cleans and snatches gave way to the squat technique. The benefit of the squat catch being that the bar didn’t have to be pulled nearly as high for the lifter to get into it. The disadvantage being that the squat catch required much more flexibility and mobility than the split clean of old.

Many lifters who were around during the transition weren’t able to make it because they hadn’t spent the years developing the needed flexibility and mobility to do the full squat position. In modern times, the split technique is almost never seen although at least one top female American lifter uses the split clean.

Now, inasmuch as the lifts were and are used for various reasons, I’m mainly going to focus here on actual OL’ing competition. Because that’s what’s really relevant in terms of the overall thrust of this article: competition.

.

Competition

Competitions in OL’ing certainly seem relatively simple although, like all sports, they have their nuances (most of which I’ll be ignoring). The basics, mind you are to lift the most weight, that’s the fundamental goal of the sport. Towards that goal each lifter is given three attempts in each lift to lift the most weight that they can a single time. It is the total weight lifted that determine the overall winner.

So when the three lifts were still being competed, whomever lifted the largest total (press + snatch + clean and jerk) won the overall in their weight class. When the press was eliminated it was simply the total of the snatch and clean and jerk. Lifters can also medal in the individual lifts so one lifter might win the snatch, another the clean and jerk and a third the total. And you do see specialists, or at least lifters with relatively better performance in one or the other lifts.

Because while the lifts certainly share similarities, they are different. The snatch is more of a speed/technique lift. Certainly it requires strength and explosive power but it’s a technician’s lift and since the weights are lighter, it’s more about speed and explosion than strength per se. The clean and jerk, in contrast, is a more of a strength lift (it’s not called the King of Lifts for nothing). Technique is crucial but since the weights are heavier more raw strength and power is needed. And it’s not uncommon to see lifters who are relatively better at one than the other.

And while it’s usually best, from the point of winning the overall, to be good at both, it’s a little more complicated than that. This is because, the different lifts contribute differently to the total because of the weights involved. The snatch allows the least weight to be used and you rarely see huge differentials between athletes at the same level.

The clean allows for larger numbers and a lifter who is ‘behind after the snatch’ can often make up weight with an amazing clean and jerk (in the same way that a guy with a huge deadlift can make up for moving less weight in the bench press in powerlifting). So someone who is a relatively weaker snatcher (hee hee) may make it up with a monstrous clean and jerk. It doesn’t really work the other way.

Note: When the press was still part of lifting competition, weights were roughly similar to what was used in the clean. Meaning that lifters who were better in the relatively more strength focused clean/press and clean/jerk tended had an advantage over the relatively more technique/speed oriented snatch. And since you had two strength lifts to the one speed lift, this meant that stronger guys would tend to be superior to technical guys. This is a very relevant point going forwards to keep it in mind.

As mentioned, lifters are divided up by weight classes and only lifters within the same weight class lift against one another; this is simply an attempt to equalize the events. It would be hard for a 60kg (132 lb) lifter to compete against a 100kg (220 lb) lifter. Within each weight class, if two lifters lift the same amount of weight, the lighter lifter will still ‘win’ on lower bodyweight. It can get even more complicated than that based on lot numbers but I’m not getting into it (I’m not sure I understand it well enough in the first place).

Lifters weigh in the day of their competition and this actually impacts on what lifters go through to make weight in terms of dehydration and rehydration. Most lifters train at a weight slightly above their competition weight and reduce weight through weight dieting or dehydration to make weight. Quite in fact, the Bulgarians OL’ing team was often caught for diuretic abuse in the drug tests; they were using them to get their lifters into the proper weight class.

It’s worth mentioning that the weight classes have gone through many revisions over the history of the sport. Perhaps one of the most far reaching changed occurred in 1993. Due to problems with drug use and the fact that clean lifters couldn’t touch the old world records, weightlifting threw out all the old weight classes and created new ones to reset the record books (because sports fans want to see records fall); it also eradicated a near 100 year history in the sport. I’ll come back to this when I touch on the doping issue later.

Unlike powerlifting where flights are performed and the weight can go up and back down (at the start of the next flight), in OL’ing, within any given weight class, the weight can only go up. So the weight on the bar will start at the lightest attempt and then either stay the same or go up; it can’t ever go back down. Once the bar is loaded, lifters have one minute to start the lift; if they fail to do this the lift is forfeited and the same rules above apply.

After an individual lifter takes his or her attempt, he can either raise the weight for his next attempt (whether or not he made it or missed it) or keep the weight the same (if the lifter missed it and wants to take it again). If someone else is lifting the same weight on the bar, they go next. If not, the next highest weight on the bar is put on and the same process continues. Again this goes from lowest to highest with the only thing that can happen is that the weight on the bar stays the same or goes up.

One consequence of this is the above is that sometimes lifters follow themselves in competition. So imagine you have three lifters who have put in 100, 105 and 110 kg as their attempts. Lifter 1 goes first with 100kg. If he misses, he may take 100kg again. Since he’s still the lowest weight he goes again. If he makes it but only wants to try 102.5 kg, he still goes again because he’s still lowest. If he goes to 105kg, the other lifter goes first and then he goes. When a lifter follows themselves, they get 2 minutes between lifts.

And trust me there’s way more to it than this involving counting attempts, changing weight on the bar (to either stall for time or for strategic reasons) that I don’t even pretend to understand. It does make following a competition hard sometimes because you’re never quite sure who’s winning or losing (and there’s no easy scoreboard to indicate it). It’s a sport that, by and large, Americans don’t ‘get’ for this reason. Too hard too follow, too confusing, no clear winner and loser and the whole going after yourself defies American sports logic. Either compete at the same time or alternate; that we get.

.

Judging

The goal of OL’ing is not just to lift the weight, it has to be lifted within specifically set rules (all of which have changed over the years). And that means that the sport has to have judges, in this case two side judges and one head judge who stands in front of the lifter.

They are highly trained, highly qualified and decide based on a red (fail) or white (pass) system whether or not the lift was done according to the rules (powerlifting would adopt this system when it was developed later in the 20th century). It also means that the sport which should be based on nothing but weight lifted has an added subjective element to it that I’m sure causes lots of sports arguments in countries that care about the sport. I wonder if OL enthusiasts call the judges ‘blind as a bat’ like Americans do with baseball umpires.

In any case we have three judges watching the lift and deciding if it meets the rules with a simple light setup. Two or more white lights and the lift is passed. Two or more reds and it fails. And as in any sport with a subjective element, judges aren’t perfect nor are they consistent. Sometimes it’s loose, sometimes it’s strict. Sometimes it changes during a meet because that’s the way real life is.

The rules are often insanely complicated and nuanced and very hard to explain or understand (I don’t pretend to understand most of them). It doesn’t help that the lifts happen so fast that it’s hard to see supposed rules violations with the naked eye. One rule infraction I can explain is press-out. If the elbows bend (or rebend) and the bar is physically pressed to arm’s length during the jerk, that’s a red light. The same holds for the snatch, you can’t catch it on bent arms and then press it to lockout, it has to go from floor to overhead with no pressout.

There are many others and sometimes two lifts that look identical will get different sets of lights for reasons you’re not always sure of. A friend (both a lifter and coach) recently went to US nationals and she couldn’t figure out why some lifts were passed and others were not. And she understand the sport. Good luck for non-lifters or non-enthusiasts to understand why Guy 1 got whites and Guy 2 didn’t and they both seem to have done the same thing (it doesn’t help that the lifts happen too quickly for the naked eye to really see what is going on).

But all of the above, the nature of the sport (2 lifts based on explosive power and most weight lifted one time) has some pretty strong implications for what is required in the sport. Which is where I’ll pick up tomorrow.

Sources

Lift Up, History of Olympic Weightlifting. Possibly the most comprehensive source for the history of the sport. This is the site where the Abadjaev interview I linked to earlier came from.

Also special thanks to Glenn Pendlay and my other OL’ing obsessed friends for feedback and fact checking on this and other parts of this series.

And with that first overview of the sport of Olympic Weighlifting, I’ll cut it for today. Tomorrow I want to get into a bit of detail of the technique of the lifts since it’s relevant to the specific physiological characteristics needed to be successful at the sport. And you might see how that’s relevant to my overall topic.

Read why the US Sucks at Olympic Lifting: OL’ing Part 2.

Facebook Comments