Can hard work beat talent? This is one of those questions and debates that has raged on for yers. Usually I see it asserted that “work can beat talent” or perhaps “hard work can beat talent”. This is meant to suggest that so long as you put in the work you can reach whatever goal you set. That includes beating someone who might be more naturally talented than you.

The fitness industry runs on trite platitudes like this.

I’ve gotten into endless arguments over the years in various forums, etc. When I try to point out that there are clear genetic limits, this will be met with the retort “You don’t know my work ethic.” The implication, belief being that hard work can overcome anything.

It’s a mentality that tends to be held by those with less talent, who want to think that life works like a Rocky movie. That heart can beat talent. Or in Rocky IV, that heart can beat steroids. Don’t get me wrong, I want to believe that too and I’m still waiting for my training montage to a Survivor song.

I’ve had repeated arguments on forums where, when you try to point out that there are genetic limits that can’t be surpassed, someone will tell me “You don’t know my work ethic.” The implication being that hard work can overcome anything.

Table of Contents

Is Talent Overrated: Part 1?

In recent years, the idea that talent (defined later in this series) isn’t important has become popularized. Books such as Talent is Overrated essentially argue that there isn’t much to the concept of talent and it’s just an issue of putting in the work (and there were many like this for a while).

This is based on the work of Anders Ericcson on deliberate practice. His early research identified that “experts” in certain fields were all marked by having put in roughly 10,000 hours of what he called deliberate practice. This was defined fairly specifically but I’d refer you to the above link for a much more involved look I did on the topic.

And certainly at first glance his work would seem to support the idea. Just put in the time (well properly) and you can become an expert. But there are several problems here, more detailed in my other article.

One is that his work did not find that simply putting in the work made someone an expert. Rather, experts all shared the commonality of having done roughly that much work (and even the 10,000 hour number was an average and a lot of people discount it now for various reasons).

Basically, the people concluding that talent didn’t matter reversed the argument from:

- People who are experts share the commonality of ~10,000 hours of practice to

- Putting in 10,000 hours of practice makes you an expert

And these are very different concepts. We all know those people who toiled endlessly at something without ever getting much more than mediocre at it. Just putting in the time, even if it’s the proper type of practice guarantees nothing. It’s simply that most people who became experts happen to have put in the time.

It’s worth nothing that his original work was in activities such as chess and music which might as well be classified as skill based. He later sort of expanded his ideas to athletics but he also believed that the only “immutable aspect of physiology was height”.

In a debate with the guys at Science of Sport Ericsson also basically argued that ANYBODY could become an elite athlete if they put in the 10,000 hours which is laughably wrong. But he was completely out of his lane at this point.

Is Talent Overrated: Part 2?

You will see the idea that talent is overrated in the athletic realm as well. And when it isn’t held by mediocre athletes who think that just grinding away for 10 more years will get them to the top, it’s held by top athletes who don’t want people to think it’s anything but their own work ethic.

This idea was really driven to the forefront of my mind as I read the books Pre and Bowerman and the Men of Oregon as well as watching one of the two movies made about the altogether too short career of Steve Prefontaine. For those not familiar, Pre was one of the great distance runners of the 70’s, setting records at a variety of distances prior to dying young in a car crash.

Famously, Pre argued that talent was a myth, that the only reason he beat people was because he was willing to hurt more than anybody. Make no mistake, his ability to suffer was legendary. But was it true that he had no talent and it all came down to his strength of will. Or was there more going on? I’ll answer that question later.

More recently is MMA fighter Conor McGregor who has argued that there is no such thing as talent. It’s just his insane work ethic and the time he puts in that took him to the top. Make no mistake, no athlete makes it to the top without putting in grinding effort. But does that mean there’s no such thing as inherent talent?

Is it even possible to talk about one or the other separately? Is it true that hard work can overcome talent in sports. Well, as is usually the case it depends on what context you’re talking about and some specifics. At least one big issue of relevance is exactly what you’re talking about. In a sporting context, what you’re usually talking about is winning, or at least reaching the top echelon of your sport.

And that’s the context I’m addressing here: winning in competition. Certainly if you pick a different endpoint, perhaps becoming extremely skilled at an activity, things become fuzzier. Getting extremely good at something (i.e. an elite total in powerlifting) is no the same endpoint as wanting to hold the world record or be the best ever.

This is actually the issue of defining what an “expert” is to begin with. Is it someone who is the BEST at what they do, or just someone who has developed a skill above a certain point. Clearly not everybody can be the best. But we’d consider someone in the Top 10 or even Top 50 to be at least one of the best.

But even that begs the question: why can’t #49 in something just put in that much more hard work to beat the guy at the top? If it’s just hard work, than the person willing to do the most of it should win. And that’s just not the case.

And with that long introduction, I want to define some terms so that the second half of this series will make sense.

Defining Talent: Part 1

Before even attempting to address the question, I want to try to define some terms, starting with talent. So what would talent mean in a sporting concept? As I discussed in the original series on deliberate practice, it’s rare for anybody trying a new sport to be particularly skilled at it (unless the activity is totally trivial to perform). At the same time, there are likely to be different degrees of suck whenever someone is introduced to a new activity.

Even at a young age people differ in their reflexes and coordination. Things like spatial reasoning or what have you can also vary. Is this innate? Maybe. Or maybe it’s early exposure. Everyone I’ve known who did sports young in life tend to have good movement skills later in life so maybe that’s just learned due to practice.

Certainly there can be differences in body size or type although most of these don’t show up until after puberty. A larger male would have an “innate” advantage in certain physical sports. In that vein, it was sort of discovered years ago that success in many sports was determined by birthday. It had to do with the way age groupings were set and males who’s birthdays fell in certain places had invariably hit puberty but ended up playing against boys who were smaller.

For females it might work in the opposite directly with smaller girls being more likely to succeed early on at something like gymnastics. Females with certain body proportions definitely are more well suited to certain sports (i.e. women with narrower hips and a more “linear” body type are built more for running than females with wider hips.

I think you get the idea.

Because the argument behind this is usually that it’s just the 10+ years of practice that took people to the top. And it’s just as likely that small differences in initial skill or talent leads to early success. And that talent is what causes the kids to continue putting in the time. Put differently, if you completely suck at something the first time out of the gate, you’re unlikely to continue with it.

The example I used in the deliberate practice series posited 10 kids introduced to a new technical sport. For whatever reason, 3 show early success (i.e. they have natural talent), 4 are in the middle, and the last 3 suck at it. Who do you expect to continue with the activity? Unless they are masochists, the 3 who sucked at it will probably quit. The middle 4 might or might not keep going.

But it’s the 3 who got early success who are likely to pursue it. They are usually the ones who also get lots of positive reinforcement and their coaches and parents invest more in them. But it was this initial “talent” (existing for whatever reason) that led them to pursue the sport in the first place, putting in the grinding hours, days, weeks, months and years that took them to the highest levels.

But that’s not the point. The point is that all it takes is for small differences in early success at something (due to some innate “talent”) to get someone into the necessary feed forwards loop that gets them to stick with the activity. As I’ll come back to the idea of talent vs. work is a false dichotomy as one can feed the other and vice versa.

Of course, some of those end up burning out too and even the ones with early success may never reach the top no matter how much time they put in. And even some of those early successes don’t have the discipline or drive to put in the work.

People like to dismiss this out of hand but consider that perhaps those strong internal drives and focus might be genetic or internally determined. Certainly they might just as easily be taught or learned but the early data on delaying self-gratification (Mischell’s marshmallow experiments) certainly suggest some degree of innate “talent” for it. The kids who showed an early ability to delay self-gratification has greater success in all aspects of life later. Just something to consider.

I’d also note that it is somewhat different for adults. It’s not uncommon to see adults who don’t have a particularly innate ability at something to keep grinding away at it. I give my own experience with ice speedskating as one example. But you can go into any gym and see guys toiling away trying to build muscle or strength and not getting anywhere at it. But they don’t stop.

Which still doesn’t change the fact that all of their “hard work” hasn’t gotten them jack squat…..

Defining Talent: Part 2

But none of the above really defines what talent might be in an athletic concept. Here I’m going to use the term “talent” very generally to include anything innate (i.e. physiological, biomechanical, or neurological) that might give someone an edge in a given activity.

Some of these might well be present in kids just starting a sport but the examples I’m going to use are equally as relevant to an adult trying to decide if “hard work beats” talent at higher levels of competitions. Because when you’re talking about margins of winning vs. losing that might be one percent or less, every little bit maters.

So what are some potential biologically inherent physiological characteristics that might give someone an advantage?

Endurance Sports

In endurance sports, a preponderance of slow-twitch muscle fibers is one. A higher than average VO2 max or biomechanics that predispose them to be successful at the sport would also be important.

As I said above, top female runners tend to be more “linear” in their body type as wide hips tend to lead to knee problems. Runners have to be sturdy enough to handle the training as injured runners don’t get very far.

You might consider swimmer Michael Phelp’s who has size 11 feet and monstrous hands which act like paddles and flippers in the water. When you couple that with his wingspan and some other biomechanical factors (i.e. many swimmers are hyper mobile or double jointed) and he’s a man born to swim. And nothing any other swimmer can do can give them hands and feet that big.

In sports like cycling, longer legs are beneficial. Miguel Indurain was mechanically built to ride a bike. He was also claimed to have lungs to big that they hung down below his rib cage. This gave him an enormous ability to exchange oxygen during cycling. Obviously certain body types are relatively more or less suited for given sports (i.e. you see very few short basketball players).

As an odd example, in ice speed skating, it’s been shown that one of the determining performance factors is the ratio of the upper to lower leg. It has to do with the push and being able to sit low but this single factor determines performance between skaters even if they have identical physiologies.

We might even consider potential psychological factors which might be innate or at least wired early on. Endurance athletes need to be able to handle what is often mind numbingly boring training. ADHD individuals need not apply for these sports.

It’s often suggested that Kenyan runners have an advantage here due to their lifestyle. They aren’t bombarded with social media and computers and know how to be bored. So running for hours per day isn’t a big deal. Contrast that to the average American who fights to finish an hour of cardio without going nuts.

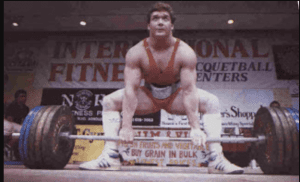

Strength/Power Sports

In strength/power sports, innate talent might be found in a higher proportion of fast twitch muscle fibers. A good nervous system (in terms of being able to fire those muscle well) wouldn’t hurt.

Hormone levels (i.e. testosterone) play a role although this wouldn’t show up after puberty. But differences in normal levels of testosterone will play a role: someone with a testosterone of 300 ng/dl is at a disadvantage to someone with 900 ng/dl.

Even for women, variations for women in basal testosterone levels are associated with performance. Women with PCOS, who often have up to double the level of testosterone as normal are at a huge advantage. Some have even argued that it should be considered a doping condition.

Biomechanics play a role here. Olympic lifters tend to have fairly specific biomechanics and you don’t see many top tall OL’ers (there are exceptions). In contrast, throwers, especially shotput and discus are on the taller and heavier side because of physics.

In powerlifting, different events may require different optimal biomechanics. The best benchers tend to have certain mechanics including shorter arms and a barrel chest. Being able to use an insane arch helps too since it can limit the range of motion to inches.

This same body type tends to be less than ideal for deadlifting since longer arms are a benefit here. I would note that powerlifting can accommodate many different body styles due to the ability to alter technique to compensate. If you have long arms, you can widen your grip to make you bench a bit better.

Ed Coan is often held up as having a nearly ideal body type for powerlifting. We might quibble in terms of his bench since it was “only” 90% of the best in his weight class but overall he dominated the sport like no-one before or after. He also pulled 405 his first time in the gym so clearly he was starting out with some sort of advantage over the rest of us.

Similarly, individuals who want to pursue strength sports have to be fairly robust. People with small joints or less dense bones tend to get broken by the training required by the sport. Certainly you can improve bone density with training but joint size is mostly genetic.

In a semi-related vein, people with a great grip almost always have big hands (the kind that make you feel safe). If you don’t have those, you’ll always be at a disadvantage for any activity requiring grip.

Bodybuilding might be the most genetic of all the sports. For years it was felt that smaller joints were a benefit as they make muscles look bigger. Having long muscle bellies and short tendons helps too. Otherwise you end up with big empty spots where no muscle can be developed. Height is an issue here because of the way height and body volume scales. To look as big as a smaller man requires much more muscle mass. Of course there are hormonal issues at work here.

Even if you’re dealing with the issue of anabolic steroids, there seem to be a genetic issue. Things like androgen receptor sensitivity, steroid metabolism in the liver and the ability to handle the drugs without side effects all have a genetic component.

Here too there is a psychological issue. Aggression helps in a lot of the strength/power sports and, to be blunt, physique athletes tend to benefit from an obsessive compulsive/subclinical (or overt) eating disorder background. It’s the only way to survive the dieting process. And most of it is going to be innate.

Mixed/Team Sports

In team sports, it gets fuzzier since the determinants of victory often lay far outside purely purely physiological factors. A better team may beat a physiological stronger team in many sports. But there are still potential places where there might be innate advantages In addition to physical factors, speed of movement, body requirements, there is the issue of tactics, reading plays, reaction time.

A quarterback in American football needs to be able to assimilate a tremendous amount of incoming data and make rapid decisions or alterations on the fly. While some of this can probably be trained as they develop over the years, it’s not far fetched to assume some of it is innate.

Quite in fact, it’s been suggested that a little bit of ADHD might be beneficial for something like this. A quarterback can’t get fixated on a single player, being able to switch focus rapidly is crucial. And it’s genetic.

As another example, there is a current interest in vision improvement, for some sports (consider an American football quarterback watching for a sack, a soccer goalie trying to watch his flank, that sort of thing), good peripheral vision would be a real boon.

Some of these things do respond to training, mind you, (one of the reasons coaches set up plays repeatedly is to teach athletes how to recognize and deal with them), but some of it may be innate or the luck of the draw.

Talent Identification

It’s worth mentioning in this regard that lots of countries such as Russia, German and China did a lot of early work into talent identification. They did endless testing on kids to try to identify who had the most potential to become a super athlete based on thing like body mechanics and physiology.

And in those countries, athletes were given no choice as to what sport they got to do. If they were built to have the potential to be a world beater in sport X, they did sport X. It didn’t guarantee that they would become a world beater of course. But choosing from those most likely to have the innate advantages to succeed was their goal.

Contrast that to most Western countries where there is basically none of this. In the US, athletes go into the sport they want to, or that their parent pushes them into or what have you. This might be based on region of the country, financial reason or others.

But the only real “talent identification” is seeing who does well enough early on to continue. Athletes who end up reaching the top tend to “luck” into the sport or activity they were innately suited for.

Defining Talent: Part 3

The above discussion of potentially innate characteristics that might qualify as “talent” leads us into the genetic issue. Now, another common argument is that “There are no such things as genetics” when it comes to training or performance.

I see this as just an extension of the “Hard work can beat talent” mentality. By saying there are no genetic limits to begin with, all it then takes is all the hard work to achieve your goal. Sadly, every bit of science on the topic says it’s not true (and factually genetics account for ~50% of just about everything we measure, the rest being environmentally determined)

Individual Training Responses

We’ve known for quite some time that subjected to the same training, individuals can vary massively in their response. Aerobic exercise was the first to identify so-called non-responders with some people responding anywhere from 0% to others improving by 50% and most getting an average response. Not everyone agrees and it may be that so-called non-responders simply need different training to get some results.

But none of that changes the variation in training response. For endurance athletes, being born with a high VO2 max is critical too. Elite endurance athletes typically have a VO2 max of 75-85 ml O2/kg/min. If trainability is only 50% and you aren’t born with a certain level, you can never reach that. I vaguely recall it being stated that people born with a high VO2 max get a better training response but don’t swear me to that.

The point is that the best endurance athletes were born with a high VO2 to begin with along with getting a high response to training. Without those two innate factors, they can never reach the upper limits of performance.

Moving to things like muscle growth, one early study found that individuals with a lighter bone structure got a much lower gain in muscle mass than those with a heavier bone structure. Of course, perhaps that just means that different training approaches are needed. The idea that the “Hardgainer” and the “Easy gainer” should train differently is as old as the hills. But so is the idea that starting joint and frame size predict muscular potential.

You can get up your butt even further and look at the 2:4 finger digit ratio which is highly predictive of sporting success.. This is an external, structural factor that is indicative of many things such as what hormones you were exposed to before you were born.

Other research is starting to identify hyper-responders to muscle growth with factors such as mitochondrial function and ribosomal biogenesis being factors here. We have all seen how some people just blow up in response to training while others seem to get little to no gains. You can even look at the data in research studies and the difference between two individuals on the same training is simply enormous.

And while it’s easy to say that the poorer responders just didn’t train as hard, in most cases the training is being supervised. It’s simply biological differences.

The Genetics of Athletic Performance

Moving to a more reductive level, studies are looking closely at the role of genetics in athletic performance and adaptability and there is certainly evidence that this matters. For example, a specific ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) type is found in elite endurance athletes, and the opposite type in strength/power athletes.

Other genetics markers have been found that relate to strength and power production. For example, the genetic marker alpha-actinin-3 is associated with speed performance and athletes who lack it will be at a massive disadvantage to those that have it.

Future research will assuredly uncover other genetics that are involved with or associated with athletic performance. Where the presence of that gene give someone the potential to be great and the lack of it essentially ensures someone will not be. Which means that future talent identification will probably involved genetic testing. And that future improvements in sport may involve genetic manipulation.

Genetic Upper Limits

Despite people’s desire to not believe in them, all physiological systems have some upper genetic limit that can’t be surpassed. In elite sport, most of those physiological systems have reached a limit. For example, the highest VO2 max levels have already been recorded and nobody is going higher no matter how much hard work they put in.

But there is the basic fact that what any given individual’s limit is will differ from some other person’s. If your genetic limit is lower, you’re at a perpetual disadvantage to them. Because no amount of work can take you past a genetic limit. That’s not what a limit is.

Whether it’s a limit to Vo2 max, muscle mass or something else nobody keeps adapting indefinitely. That’s one of the big reasons athletes use drugs (yes, newsflash, athletes use drugs). Not only do they provide numerous other benefits such as improved recovery or what have you, they artificially raise the inherent genetic limit of the body that, otherwise, wouldn’t be surpassed.

Even if that average 10% improvement with drugs doesn’t seem like “a lot” it puts athlete in a different zip code. The first and last competitor in many events may be decided by less than 1% in performance. 10% is enormous. And while you could argue that adding 10% to everyone doesn’t change anything, that’s clearly not true.

Just as in bodybuilding, differences in drug response will play a role. If you have two athletes one of whom is 1% behind another and both go on drugs all it takes is for the second place athlete to get a 1.5% greater drug response to take the lead.

Other Genetic Aspects

To the above we might add other things that would show up as “talent”. Good body control, coordination, proprioception, things like that. At least some of this seems to be innate with even young children showing better inherent levels than others (i.e. consider the “Accident prone” person who just seems to bump into stuff all the time.

Those kids are likely to be drawn to and/or succeed in certain sports than kids who are not. Gymnastics, ballet, and probably most sports are simply not for the uncoordinated. That’s what towel and water boy positions are for.

Defining Talent: Summary

My point being that there would certainly appear to be some inherent physiological aspects that relate to sport performance that can show up as innate “talent”. Certainly some are modifiable with proper training, but some are not. And there is clearly a difference in how well or poorly someone will adapt to training with increasing evidence that this is determined genetically.

I’d note before moving on a concept that seems to escape many, which I’ll leave for now simply as an unanswered (and possibly unanswerable question): is it conceivable that part of what makes people willing to put in the 10 years of grinding work to get good at something is an innate characteristic?

It’s easy for trite fitness professionals to say that “What separates great athletes from good athletes is discipline” with the implication that you just need to have discipline. But why is it so hard to believe that this might be an innately wired thing. Personalities differ and some of this is in-built.

If you don’t believe me, just go work with animals for a while. Different dogs of the same breed can have distinct personalities. Why is it so impossible to think this is true for humans? You and me, baby, ain’t nothing but mammals after all.

Perhaps great athletes, on top of any other innate advantages may have a personality profile where they are willing to devote 10+ years of their life to a pursuit with zero potential rewards. There are only 6 spots on the women’s gymnastics team. Yet thousands of young girls pursue the sport. Even here, the year they are born in can be the difference in success or not. You can’t compete in the Olympics if you’re under a certain age. If girls miss the age cutoff and have to wait 4 years, they may hit puberty and their career is over.

So having attempted to define “talent”, let’s switch gears and try to define “hard work”.

Read Can Hard Work Beat Talent Part 2

Similar Posts:

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent: Part 2

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent: Part 4

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent: Part 3

- Success Leaves Clues

- Train Like an Athlete, Look Like an Athlete

Thanks-very interesting Lyle. My thesis adviser was a Hungarian Olympic water-polo athlete in the mid 70’s. When I asked him about their training methods at the time- his reply was that the best athletes were the result of “sheer talent”. Not sure what talent is either? I think a good example maybe for clarification is to compare athletes to that of musical “genius”. Even a great music protegee must learn the mechanics of piano playing for example and then “innate” abilities allow them to play and compose at a much faster rate the “normal people”. However why they have these distinct abilities becomes a matter of why there is variation in humans generally and if due to evolution then certain evolutionary adaptations have become adapted well to games and arts. Not surprising since many sports are substitutes fro physical conflicts (ie. wrestling vs.fighting to the death) and therefore play an obvious evolutionary role. Just some thoughts!

I get tired of hearing endurance athletes tell me I could be a good runner if I only trained right. I ran competitively for long enough to know it ain’t going to happen. On the flip side, I think you’d be hard pressed to find an endurance athlete who can run 100 meters faster than me.

It is rather absurd that people can simply ignore talent and only emphasize hard-work. That is either naivete or simple ignorance. In real life, in every single fields, you need BOTH talent and hard-work to belong to the top percentile. No matter how hard a regular person tries, he won’t be able to be better at math than a math whiz who got invited to MIT when he’s 14. No matter how hard a regular person tries, he won’t play better golf than Tiger Woods. And no matter how hard a regular person tries, he won’t be able to compose better than Mozart. PERIOD.

You always need right raw ingredients where you can base your hard work on. If you don’t have those necessary ingredients, no matter how hard you try, you’ll never catch up those people with them. You might be better than a regular person in that field for putting so much effort into the field, but face the cold truth. There is such thing as LIMIT.

My legs develop at the drop of a hat but I have to work real hard at upper body stuff. Like Stephan I’ve done a lot of running but will never excel at distance running, I look at the strides of the people who can really motor and it just isn’t within the realm of possibility for me to do that with my frame.

I grew up with a guy who played major league baseball for nine years and he was an exceptional athlete when we were 8 years old … no amount of hard work would have made me his equal, and baseball was my best sport.

People who argue that hard work trumps talent have never spent any time around high level athletes.

I work around several guys who have been successful at sports ranging from high school to D3 to D1 athletics and you can tell a distinct difference very quickly.

It’s not surprising that the biggest winners are usually hard workers. They also happen to be talented hard workers. Can untalented hard workers keep up with talented slackers? Maybe, but neither are going to be at the top of the heap when the dust clears.

The top – the real top of the big piles, the sports that pull in big numbers of competitors – is always made up of people who have the talent and bust their asses. It’s the difference between a Shawn Kemp and a Tim Duncan. One has rings, the other got fat and forgotten.

I’m with Stephan. I was never able to run a sub 15-min 5K, but I also know I can outkick any marathon runner (I was a sub 1:55 800-meter runner at some point in the past haha). That’s MY talent. It’s also why I picked basketball as a sport, where middle-of-the-road in many physical and skill attributes can take you pretty far, paired with hard work of course (compared to the shear and specialized talent (and work ethic) needed to be a 100-meter sprinter or a Tour de France champion…). Until you have to come to grips with the fact that you are “only” 6’2″, white and from Canada (OK, tell me Steve Nash worked harder than I did… Or maybe he had more talent… Which one was it?!!?).

Anyways, I’m a great Prefontaine fan… Ability to suffer on par with the greats, for sure. Talent. Yeah, definitely more than he would have liked to acknowledge. That scene at the Pad, where Bowerman (Sutherland) gives Pre (Crudop) the spiel is a classic…

Top-notch talent often takes athletes all the way to the college level, sometimes where they’ll even excel. Once you’re in the pros though, and especially if you want to be the best of the crop, there is no way talent or work-ethic alone will cut it!

Talent and hard work are required to be successful and the old maxim of “practice makes perfect” comes to mind.

I hate it when people say “well I wish I could be good at X like you.” As if you are born with some magic power that allows you to do things better. There are strengths and weaknesses and freak strengths and freak weaknesses but any aspect of any activity is conditioned to a great extent be what we learn. It’s just that most are deterred from trying anything they are not immediately good at or show promise for.

It’s like:

I suck at sprinting. That’s because of some factor out of my control to do with genetics so I’ll just stick with long distance.

or

I suck at sprinting. Now I do plyometric drills, squats, deadlifts and sprint training to get better at sprinting.

Ok some people have more maximum potential than others but generally most can improve at anything to a significant degree. Most of the time if you say you can’t do something for whatever reason you are probably lying to yourself and it is just difficult.

To quote Jordan Belfort:

“The only thing that stands between you and your goals is the bull**** story that you tell yourself as to why you can’t achieve them”

David… With regards to Jordan Belfort’s quote, you still have to account as to what those “goals” are… It would be irrealistic for me (and most people who didn’t choose the right parents, which is probably over 95% of the population) to set the goal of beating Usain Bolt’s 100-meter world record, no matter the resources made available to me or how hard I work.

On the other hand, stating that I want to be the best sprinter I can be, that’s another story. I think that’s the point Lyle is trying to make here… You can get better at everything relative to your starting point however, there is a genetic potential we are all endowed with and over which we have very little control. Expressing this potential to the max and saying I can be the next Olympic weightlifting champion are two goals, but stated differently…

Read Part 2 guys. Because drawing conclusions from Part 1 of what’s going to amount to a 3 part series is kind of premature. Invariably what you think I’m saying isn’t what I’m saying but you won’t know that until I actually say it.