So I know I promised a video to wrap up my reposting/rewriting of the Training the Obese Beginner series but, honestly, it was just going to be pointless ranting and I seem to have lost the fire in my belly to do it right now (to be honest I think I just didn’t want to deal with the shooting, editing and transcribing part of it). So here’s some actual new content instead. Today I want to talk about surviving indoor aerobic training.

While we can probably argue until the end of time what the “worst” part of training is, I imagine that most would be willing to put indoor cardio (especially of the steady state/aerobic type) right up there near the top.

And while certainly one way to avoid the issue is to either take the no-cardio or intervals only approach, I don’t think either are ideal. The simple reality is that whether it’s for fat loss, general fitness, or for endurance athletes who live somewhere where it’s cold, doing longer duration indoor cardio of some sort is usually a necessary evil.

So today I want to talk about some strategies that can be helpful to help folks get through it or, at the very least, maybe enjoy it more. And I’m not going to bore you with the obvious strategies, listening to music, reading a magazine or book to kill the time or whatever. You know that already.

If you’re lucky maybe your gym has a cardio theater where you can watch movies; in my experience all that ends up happening is that you end up watching the same middle of the same crappy movie (when I was in Utah, I must have seen the middle hour of the horrible Queen Latifah/LL Cool J movie “Last Holiday” a solid dozen times).

Instead I’m going to suggest a way of modifying/thinking about your indoor aerobic sessions both to make them less psychologically gruelling (read: “boring as hell”) as well as physiologically more beneficial.

Table of Contents

The Inevitable Driving Analogy

For reasons I’ve never quite figured out, when people write about weight training they have a tendency to use car analogies. Probably just because cars are something most people understand. Or because they go “Vroom” or something. Regardless, that’s how it is and I’m going to continue with that tradition here.

I imagine that most reading this have had the experience (or misfortune, depending on how you want to look at it) of driving long distances. When I was in college, for example, I did the drive from Tennessee to Los Angeles (2214 miles, a value forever burned into my head) a number of times.

Once without sleep jacked up on caffeine and sugar but that’s a different story. And you know that it’s just awful to contemplate especially if you look at the distance all at once; when you’re faced with 24 or 36 hours of total driving, each minute or even hour just doesn’t seem to be having an impact.

Invariably what people do in this situation, certainly what I did, is to break the drive up into more manageable “chunks”. So the first mental break you make is at the half-way point (or whatever distance you might cover in a day’s worth of driving). So it might be 12 hours.

Ok, 12 hours is a lot easier to deal with than 36 hours even if you have to do it three times. Or maybe you break it up into an even smaller increment. Now you’re at 6 hours (how far you get between fuel ups if you have a really efficient car). Well everybody can drive for 6 hours, right? I think you see where this is going.

I vividly remember that, leaving Nashville en route to LA, there was a major city about every three hours. That synched up rather nicely with both my need to stop for gas and my need to go to the bathroom and refuel with caffeine. So mentally I wasn’t thinking in terms of having to drive 36 hours.

I only had to make it the next three hours. And the next three. And the next three. By chunking it in this way, you’re never facing down the entire distance and your brain can sort of “reset” once you hit each intermediate time point. You hit three hours, reset, now you have three more hours to drive.

Of course, as anyone knows, this can be taken too far. Certainly it’s easy to think of “I only have to drive an hour” or even “Only a minute” but at that point you’ve reached the other extreme. Because 36 by 1 hour isn’t really much better than 1 by 36 hours (or whatever this works out to in minutes or half-hours). Somewhere in the middle is a happy medium where each chunk is a reasonable length and you can divide the entire distance into a reasonable number of chunks.

Here’s a graphic to break up the dense text and attempt to make this a bit clearer. The arrow is the full distance start to finish, the lines are then subdivided at different time points: 1/2, into thirds, into fourths, sixths, twelfths.

You could keep going but, again, you reach a point of diminishing returns where you know have an immense number of small increments rather than one large increment. Somewhere in the middle where you get a reasonable number of reasonable length increments is invariably the mental (and physical) sweet spot.

Man I’m good at drawing.

Lets Apply This to Indoor Endurance Training

And, as you can imagine, I’m going to suggest applying the same concept to indoor aerobic training (I’d note only in passing that you could very easily apply this equally to high repetition weight training. So rather than think of a 20 rep squat session as 20 reps, break into into 4 sets of 5.) as a way to mentally break up the time into more manageable chunks.

So a 60 minute workout becomes 4 blocks of 15 minutes, or 3 blocks of 20 minutes or even 6 blocks of 10 minutes. A 30 minute workout could be divided into two blocks of 15 minutes, three blocks of 10 minutes or even 6 blocks of 5 minutes.

There’s no reason you have to make each block an equal time. For example, a 60 minute workout might have a 5 minute warm-up and cool-down leaving 50 minutes in-between to be divided up into varying lengths (you might divide that 50 minutes into 5 ten minute blocks or 10 five minute blocks). There are endless options.

I’d also mention that in every example, it’s not just a function of chunking but of changing something at the time break. This is where it differs from the driving example. Every time you reach the end of a block, you’re going to do something different as that sort of signals the “end” of that block.

This tends to get you thinking only of the duration of the time block you’re actually in rather than focusing on the length of the entire session. Not only is this psychologically more manageable, by choosing what you do during the workout, you can impact on the physiological adaptations and training effect. So it’s a double win.

This should make more sense with some specific examples and I’ll be moving from shorter to longer in terms of what happens at each block.

Fartlek Training

.Fartlek is an old Swedish (or is it Scandinavian?) training concept that translates roughly as speedplay. It was developed in the mid-20th century by Swedish/Scandinavian running coaches. It was simply a way to break up longer runs, invariably done outdoors, while also introducing some unstructured speed work (i.e. it wasn’t formal interval training). This was also more reflective of competition demands.

It would typically be done during an easier part of training when the goal was on distance and volume but the coach wanted to keep a bit of speed work in the program (and to keep the athlete from going nuts). So early in the “base” period, some of the longer runs would include Fartlek.

The key here was that it was unstructured, an athlete might be running in the woods and come up on a short uphill. They would then pick up the pace up that hill. Or they’d introduce a short “sprint” to some tree they saw in the distance. This would be done before returning to the easy pace of the run.

Cyclists have long done this sort of thing on long rides, especially in groups. So you’ll be in the middle of 4 hours in the saddle and everybody will do a group sprint to the next light pole or the signpost. Everybody throws down for a little bit and then you go back to gradual riding before the next sprint. Years ago some endurance book I read recommended a 15 second “sprint” every 15 minutes on the bike. It gets a little speed work in and breaks up the mind-shearing monotony.

“Structured” Fartlek Training

Indoors, mind you, it’s probably better to use something I call, somewhat contradictorily, Structured Fartlek training. The issue here is that you don’t have the types of natural targets that would occur outdoors like an uphill or what have you. Though I suppose you could use a TV commercial or particularly upbeat song on your MP3 player.

But the idea of structured Fartlek is that you structure your speed bursts based on the total workout time. So like the bike idea above, you decide to insert a higher paced section at whatever block length you choose. Wanna go hard for 15 seconds every 5 minutes? Great. Wanna go 30 seconds hard every 7.5 minutes? Sure. Whatever works works.

As an example, a buddy of mine has been grinding 30 minutes on the Versaclimber and was getting bored with it. I suggested that he introduce a 15 second “pick-up” (an increase in intensity that isn’t all out but takes him out of his normal steady state zone) every 5 minutes before returning to his normal steady state pace. Now his workout has gone from “30 minutes of boring grinding” to 6X5 minutes with 15 seconds faster. Mentally he’s only having to do 5 minutes (ok, 4:45) before doing something else.

This approach really has no downsides, although hardheads have a tendency to turn the speed bits into all-out sprints which really isn’t the goal. It’s just a way to introduce some speed, work a little bit harder, and break up the monotony but don’t go nuts on the hard part of the Fartlek.Moving on.

Aerobic Interval Training

.I’ve mentioned the concept of aerobic interval training previously, usually in the context of taking untrained beginners but it also has use for people who are already trained. I want to make it clear from the get go that this is absolutely NOT HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training) and shouldn’t be confused with such. The goal is still working in the aerobic training zone but in a more interval fashion. This will be easiest to explain with an example.

So on a lot of indoor endurance machines, there are “levels”. It’s not like a treadmill where you can increase speed or incline gradually, you go from level 8 to level 9. And what happens is that you often find that the jump from 8 to 9 is too big. It goes from being too easy at level 8 to too hard at level 9. Even if it’s not too hard, it may take you out of your goal training range in terms of heart rate.

So say you’re on that machine and go comfortably for an hour at level 8. And jumping to 9 takes your heart rate too high to you can’t complete the full hour anymore. Well you can use the same chunking approach I described above to gradually increase the amount of time you can do at Level 9 while still completing the workout. In my experience, since this is still aerobic training, doing 5-10 minutes at the higher level alternated with similar amounts or longer at the lower intensity work well.

Aerobic Interval Training Progressions

So you’re doing your 60 minute workout broken into 4X15 minute blocks. During each block you might do 10 minutes at level 8 and then 5 minutes at level 9. You’d repeat that a few times. The next progression could be the same 60 minutes divided up into 3X20 minute blocks. Here you would do 10 minutes at level 8 and 10 minute at level 9.

After a few of those workouts you’d go back to 4X15 minute blocks with 5 minutes at level 8 and 10 minutes of level 9. After a few workouts you’d move to a full hour at level 9. Depending on your aerobic workout frequency that might take a full month. But at this point you’re probably handling level 9 at the same effort and heart rate as you were hitting at level 8. You’ve adapted. Now you stay there for 2-3 weeks to stabilize and do it again.

As another option you might choose to divide your 60′ into 3X20 minutes divided into 15 minutes at level 8 and 5 minutes at 9. A few workouts later do 10′ at level 8 and 10 minutes at level 9. Then 5 minutes at level 8 and 10 15 minutes at level 9. Then you’d do the entire workout at level 9.

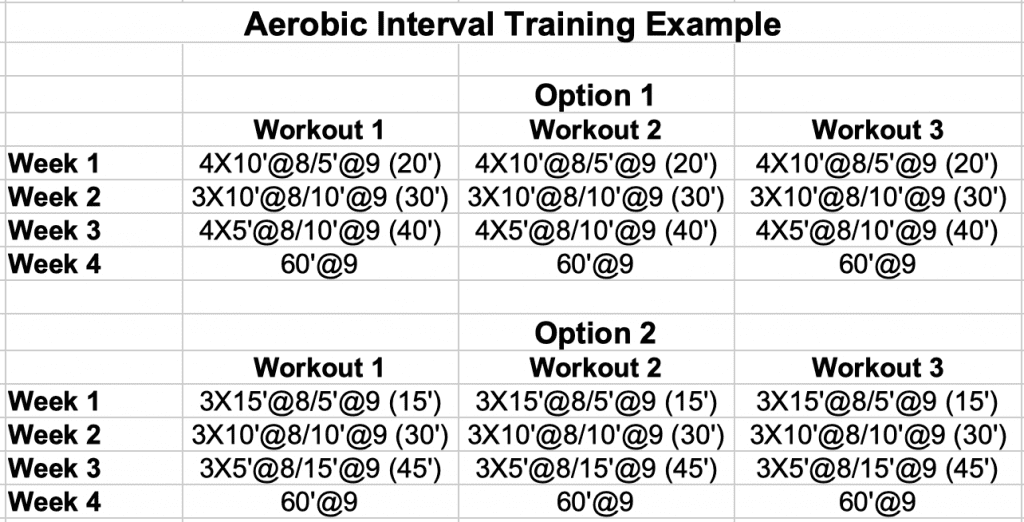

I’ve shown this in table form below. The number in parentheses is the total time spent at the higher intensity level and you can see how it increase each week.

You will notice that Option 1 skips a week with 50 total minutes at the higher workload. I suppose you could do 4X2.5’@8/12.5’@9 but it doesn’t seem necessary. When the intensities are in a fairly aerobic zone, the jump from 40 minutes to an hour just isn’t that problematic from Week 3 to Week 4.

Option 2 is a bit more aggressive in terms of the jumps every week since they are going up 15 minutes per week rather than the 10 minutes of Option 1.

Finally, I’d mention that this works best when you’re well within the aerobic zone or a heart rate of 140-160 or so. Usually you hit something like 140 for the lower intensity and will get to 160 or a bit higher at the higher intensity before having it fall again. It’s all still aerobic or should be unless your threshold is very low.

Aerobic Interval Training at Threshold/Sweet Spot

This approach can also be used when you’re working closer to your functional threshold or sweet spot but you have to use smaller time jumps. A typical workout here is a warm-up followed by 2 sets of 20 minutes close to all out with only a 5-10 minute rest between sets.

At this intensity adding 5 minutes at the next higher workload may simply not be possible. The workout is also already mentally gruelling to begin with. Once you start the work set, it’s just 20 minutes of unrelenting pain and discomfort. Here, perhaps moreso than with aerobic training, breaking things into smaller chunks can be a lifesaver.

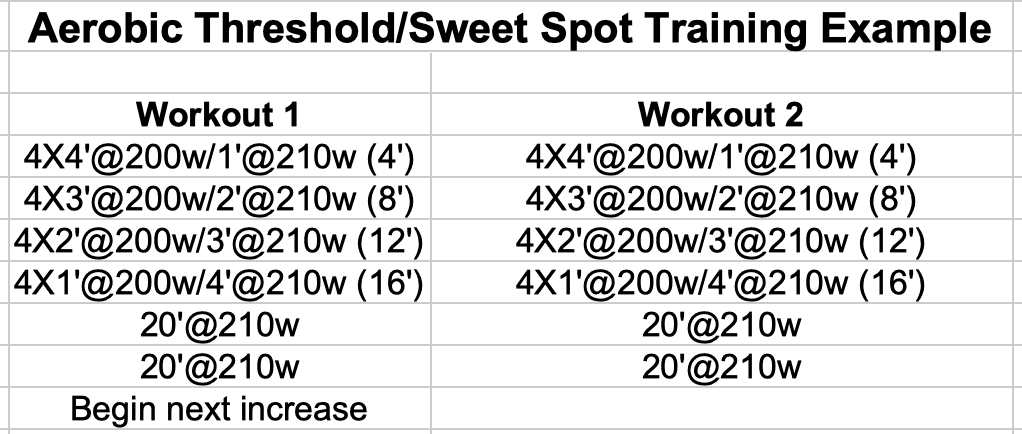

In this case I’d suggest breaking up the 20 minute work set into 4X5 minute chunks and add 1 minute at the higher workload every 2-3 workouts. So let’s say you’re currently pushing 200 watts on the bike but want to start working towards 210w for a 20′ block.

A progressive over 12 workouts, which might take 4-6 weeks depending on you training frequency is shown below. Again, the numbers in parentheses are the total time at the higher workload. After you reach the new target workload, you’d stay there a few weeks to stabilize before starting the next push to 220w.

I’d mention that this workout is already chunked to some degree. It starts with a 10-15′ warmup (one chunk), before the first 20′ work set (one chunk) to a 5-10′ rest interval (one chunk) to another 20′ work set (one chunk) to the 5-10 minute cool-down (the final chunk). So although the workout hurts like hell there is never more than 20 minutes before something about the workout changes.

Progressives

This approach to a workout probably has a formal name but I have no idea what it is so I’m going to call it a progressive workout. Now in the three previous workout examples you bumped up from a lower intensity to a higher intensity before moving back down. In this workout you start easy and progressively increase the intensity all the way until the end.

The first set to setting up a progressive workout is to pick your training range, the low- and high-end workloads you’re going to use. It could be set in terms of heart rate, pace or power output. Then the full workout, here I’m assuming an hour would be broken into 3 separate blocks.

The first block is at the low-end workload, the second block halfway in-between the low- and high-end workload and the third block is at the high-end workload. It’s a good way to both stay sane along with getting some good volume along with some intensity in the workout.

Base Aerobic Phase Example

So let’s say it’s early in the season and you’re just laying down some aerobic base. For a progressive workout you might set a training range of 130-150 beats per minute as your low- and high-end workloads. A 60 minute workout would consist of 20 minutes at 130 heart rate (a very easy aerobic/warm-up pace) before moving to 20 minutes at 140 and finally 20 minutes at 150. For a thirty minute workout, do 10′ at each heart rate. For a 90′ workout (about the limits of indoor training), do 30 minutes at each heart rate.

The main benefit of this workout is just to break the monotony. You get a nice hour of aerobic training at varying intensities but get to do something different every 20 minutes.

Later Aerobic Phase

Later in the season, ideally before moving outdoors or starting racing, this workout could be intensified and taken closer to threshold work. Here you might set a range of 130-170 heart rate (or the accompanying pace/power output).

For a 60 minute workout, you’d do 20 minutes at 130, effectively a warm-up but still in the aerobic range. In the next 20 minutes you bump to 150. This is the high aerobic range but still doable. Then for the final 20 minutes you go to threshold/sweet spot at 170 heart rate.

This is apparently a popular approach to training with Kenyan runners. They will start in a big group at an ambling pace to get warmed up but by the end of the run they are running all out/at race pace. They get volume, they get intensity, it mimics race dynamics and it teaches them to push when it gets hard. They just do it outdoors.

This approach to training has a number of benefits. A primary one is allowing endurance athletes to get a nice balance between volume and intensity. This is especially crucial for endurance athletes in trying to build a base during the winter.

Doing long workouts indoors is a grind but just cranking out threshold sets of 20 minutes may not build the longer duration endurance needed. This workout lets you do the 20 minute of threshold work while getting an hour of endurance work too. It also teaches you to push harder in the face of fatigue, something that happens during races.

Mimicking Race Conditions

You can even take this further to truly mimic race conditions. Please note that this is a workout to do occasionally, not all the time). Here you have the last block increase towards an all-out sprint at the very end. So you’ve got your 3X20 minute blocks. You go 20 minute easy, 20 minutes medium and now you’re in the 20′ hard block.

In that final 20 minute block you would do the first 10 minutes right at race pace. This is basically your functional threshold power on the bike or top 1 hour running speed. It’s the maximum intensity you could maintain for an hour. Then you push up above race pace for the next 5 minutes. This is about VO2 max tempo, it’s not all out but it’s definitely above your steady state. You will be breathing like a freight train near the end of it.

But you’re not done yet. For the last 5 minutes you now try to go faster with each increasing minute. Push the running pace, push your wattage up by 10 watts. The clock is your carrot and the goal is to get to 20 minutes with nothing left in the tank or just run out of gas from exhaustion. Every second you keep going gets you closer to the finish line and sweet sweet release.

This workout accomplishes the same thing as the previous approach, just with more suffering involved. It breaks up the workout into much easier to deal with chunks although the intensity of the workout makes it less than easy. It lets the athlete get a nice balance of volume and intensity.

And finally it teaches them to push and push and keep pushing until there’s nothing left. Because that’s what happens in hotly contested races. When its neck and neck, whomever can keep turning their legs over in the face of unrelenting pain is usually the one who wins.

How to Survive Indoor Aerobic Training

So there are some ideas to survive indoor aerobic training. Ways of making the workouts at least more psychologically manageable even if some of them are still pretty physically miserable. The basic idea, of course, is to break up longer workouts into smaller pieces where something changes every so often.

And, I’d mention, the above isn’t meant to be comprehensive. I’m sure readers can come up with their own flavors or personal favorite workouts. They can also be combined in some cases. If you want some real fun add structured Fartlet training to a threshold workout.

So the goal is now to do 20 minutes at a maximum effort and go ABOVE that level for 30 seconds every 5 minutes. This too mimics some aspects of racings. It also hurts a lot.

Facebook Comments