While I’m trying to muster the energy to do an update to my training volume series (which is not and will never be called a Bible because…well….pretentious much?), I figured I’d address a related topic: training frequency. Now I’ve written about training frequency before, mainly looking at different “popular” approaches for hypertrophy training. Here I want to address a current idea in the fitness industry and ask the question “Does training frequency matter?” For the most part, I’ll focus on growth although I might switch and talk about strength a little bit too.

Defining Training Frequency

As always, let’s define some terms to ensure that we’re all on the same page. Training frequency, at first glance, seems fairly simple to define. It’s how often you train (and here I’ll be talking specifically about weekly training frequency). If you train five times per week, your training frequency is, well, 5 times per week.

And in some sports, that’s certainly the case. If a runner runs every day but Sunday, their training frequency is 6x/week. If they run twice every day and take Sunday off they run 12x/week. Well, that holds until you start adding other workouts. What if they lift weight twice/week on top of their 12 runs per week? Now their weekly training frequency is 14x/week (some would call this 14 training units per week) although their weight training frequency is only 2X/week and their running frequency is 12X/week.

Mixed sports run into this too as athletes might be performing multiple types of workouts at different frequencies per week. So a soccer player might run or do aerobic conditioning 3X/week, lift weights 2X/week, practice soccer 5X/week and take acting classes 2X/week so they can make convincing flops. Their weekly training frequency would be 12X/week with each specific workout having its own weekly frequency.

Training Frequency in the Weight Room

And then there is the weight room which has its own specific issues. Here the issue is that weight training can be done in so many different ways. Some train the entire body in one workout while others uses various types of split routines.

Related: What’s the Best Split Routine?

Performance athletes may train different exercises with different frequencies and all of this leads to a situation where the weekly training frequency, the per muscle or per exercise training frequency can be completely different.

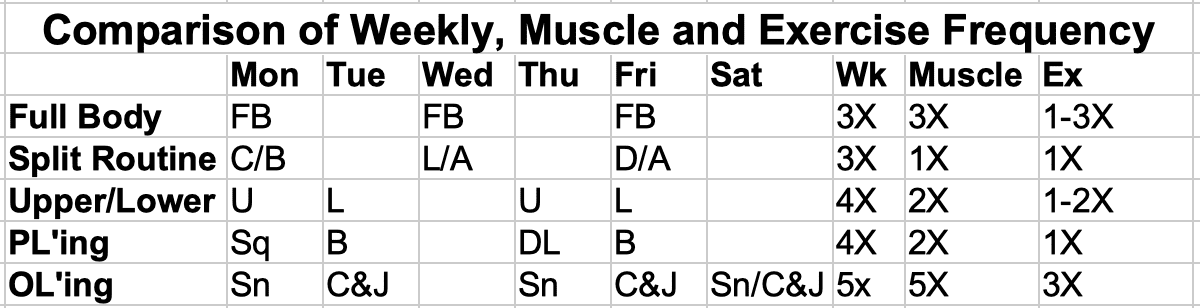

I’ve shown some representative patterns below to illustrate this:

The first example is a typical full body workout where the entire body is worked on every training day. This makes both the weekly and per muscle training frequency the same at 3X/week. I have exercise frequency listed as 1-3X/week since it’s equally possible to do the same exercises at each workout as to vary them. The latter approach is common in a heavy, light, medium approach to training.

In the bodybuilder style split routine, chest/back is trained on Monday, Legs/abs on Wednesday and delts/arms on Friday. Here the weekly training frequency is still 3X/week but the per muscle and per exercise frequency is only 1x/week.

In the upper/lower split routine, you can see that there are 4 weekly workouts with each muscle group being trained 2X/week. If the same exercises were done on each upper and lower workout, the per exercise frequency would be 2X/week. If different exercises were done on each day, exercise frequency would be 1X/week.

The PL’ing routine is a fairly old school approach where squat and deadlift each have their own day and bench is trained twice per week. Here the weekly training frequency is 4X/week with the muscle group frequency being 2X/week (since there is some overlap with squat and DL) and the per exercise frequency being 1X/week (actually 2X/week for bench but I was too lazy to redo the chart).

Finally is an OL’ing week where snatch and clean and jerk each have 2 individual days during the week and both are trained (perhaps in a competition mimic) on Saturday. This gives a weekly training frequency of 5X/week, a per muscle group frequency of 5X/week (sort of, Ol’ing is weird) and a per exercise frequency of 3X/week.

Got it? In the weight room there can be anywhere from no difference to a large difference between the weekly training frequency and per muscle or even per exercise training frequency.

And with all of that said, I’ll say that going forwards, I will be focusing almost exclusively on the per muscle group training frequency, especially for hypertrophy. Here, the number of weekly training sessions per se don’t really matter outside of any impact they have on the per muscle group training frequency.

Rather, it’s the number of times a given muscle is trained (and this is true whether or not the exercises done are the same). For strength it’s a little more complex and I’ll only touch on that as needed which is to say not much at all.

Training Frequency and Muscle Growth

So let’s talk about the issue of training frequency and hypertrophy. Outside of research, this has been an area of some debate with many still arguing for the classic “Bodybuilder” approach of training everything once/week for a large volume and others recommend distributing volume into two or even three weekly workouts.

More recently, in the fitness space, the new fad (sorry, I mean trend) is to push for very high frequency training programs, working each muscle group 4-5 times per week in some cases. Various rationales are typically given but, honestly, most of it is probably to push e-book sales.

That said, at least one research group has argued that training frequency is the overlooked training variable. Their basic logic is that increasing absolute load (weight on bar) is eventually limited by slowed strength gains and other approaches are needed to maintain progress.

True but, as I’ve argued extensively, when strength gains stop is when you stop growing anyhow. You can increase frequency or volume or whatever the hell you want but the only thing that’s going to get you growing again is anabolic steroids.

That also argue that increasing sets per workout is only worthwhile up to a point because eventually you reach some limit above which more sets don’t stimulate further growth. This is woefully understudied and unfortunately two recent studies both by Barbalho et al., one on women and one on men, appear to have issues (to put it mildly). The men’s study was already retracted and the women’s study probably will be too so I’ll be ignoring them here.

Thus they contend that increasing frequency is the only way to meaningfully increase the training load and stimulate further adaptation. They are basing this not only on the above but on the, admittedly acute, response of protein synthesis to training which may be done by 24 hours in trained individuals. Some of the fad (sorry, TREND) following fitness professionals make the same argument.

They do however acknowledge that acute increases in protein synthesis may not be indicative of muscle growth. I’d add that Damas in 2016 found that AFTER the body dealt with the first 3 weeks of repairing damage, there was a very high correlation between the acute protein synthesis and growth.

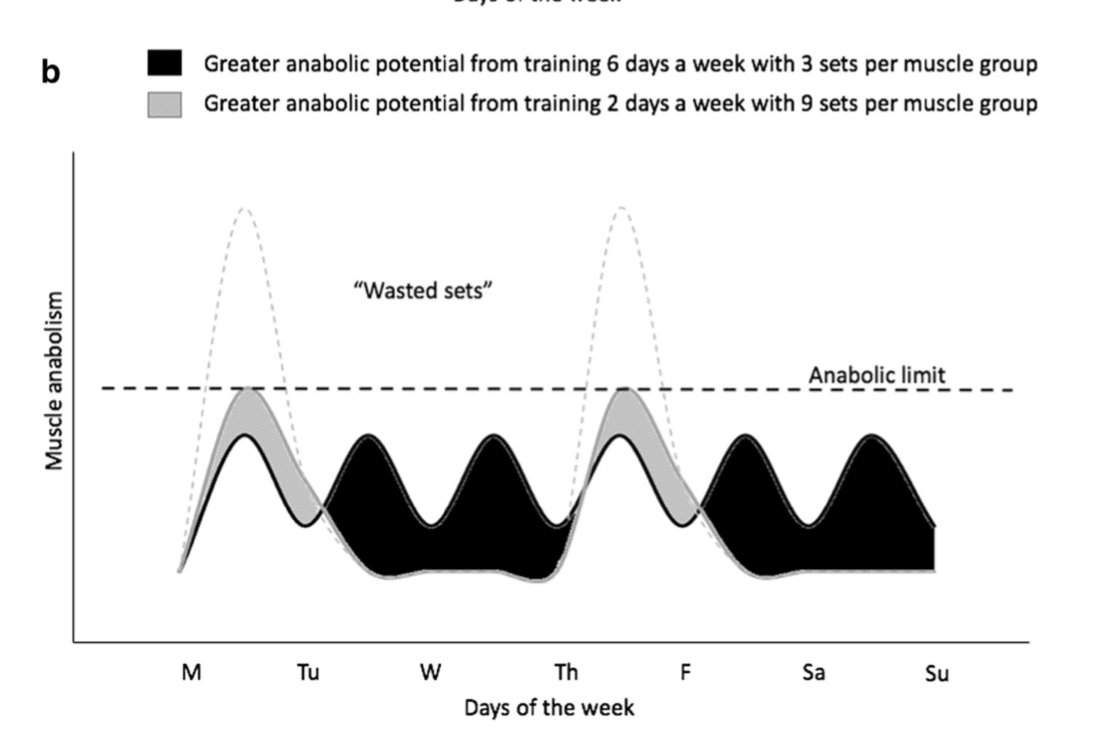

In any case, their basic model in terms of the potential benefits of a higher training frequency looks like this:

The basic idea being that doing 6 sets twice/week may be suboptimal due to the number of sets being above the anabolic limit and being “wasted”. The anabolic potential is shown by the light shading. Comparatively speaking, 3 sets three times per week keeps each workout under some theoretical limit, resulting in a much larger total anabolic potential (the total area of the black shading).

Let me make it clear that I am not agreeing or disagreeing with their set count values. For right now, just focus on the principles. ASSuming that there is some per workout set maximum above which there is no further stimulus, at some point it makes more sense to distribute the weekly volume across more workouts.

They conclude:

that increasing the training frequency, as opposed to the training load or sets performed, may be a more appropriate strategy for trained individuals to progress a resistance exercise program aimed at increasing muscle size.

They also mention that after some time period increasing training frequency, a decreased frequency may be warranted, speculating further (and wrongly) that this will re-sensitize the muscle to growth. I could write another entire article on this concept of re-sensitization but I’ve yet to see anything approximating good human data to support it.

But this was basically just a theory piece and they even acknowledge that the available data is slim. They also propose some models that might be tested to help see if their hypothesis is true. This type of intellectual honesty puts them head and shoulders above a lot of research groups.

And that’s great and all but raises the question: what does the actual direct research on the topic of training frequency say?

Before getting to that, I need to address a related topic.

The Volume Issue

I need to address a slightly tangential issue before getting into the research itself. Now, research can be difficult, and weight training especially so because you’re manipulating multiple variables. Frequency, volume, intensity can all play a role and how you change them, or if you change more than one of them at a time can impact on the results that you see, or think you see. It’s key to realize that all three of these interact in ways that are beyond the scope of this article. But it makes comparing research in this field problematic since every study seems to use a different damn training structure.

Related: What is Training Intensity?

In any case, many early studies and early analyses suggested that a higher training frequency did in fact generate more size or strength gains. But there was a problem. That problem was that the way the workouts were set up, the higher frequency group was doing more total weekly volume.

Related: How Much Volume Do I Need to Maximize Muscle Growth?

So consider a study where the goal is to compare 1 vs. 3 days/week of training. So the researchers have the trainees do 3 sets of chest on Monday or 3 sets of chest on Monday/Wednesday/Friday. And well, they find that the 3 days/week group does better.

The conclusion? A higher frequency of training is better since 3 days was superior to 1 day per week. But there’s a problem that should jump out at you rather immediately. In this example, the higher frequency group did more total weekly volume: 9 sets vs. 3.

So you have two variables changing: frequency and volume. And that makes it impossible to compare or draw meaningful conclusions. You don’t know if the increased frequency, increased volume or both drove the difference. As frequently as not in this situation, the higher frequency does generate superior results but it’s most likely due to the increased volume being done.

So when looking at this topic and trying to separate out frequency from the other variables, it’s important to only look at studies where weekly volume is the same. So researchers might have subjects do 9 sets 1X/week or 3 sets 3x/week.

Now it’s 9 total sets/week and the comparison is only the differing frequencies. And in terms of addressing the issue of training frequency only, these are the only studies of relevance.

Now, don’t get me wrong, increasing frequency can be a way to increase volume per se which is what the section above discusses. If you have topped out what can be done at a single workout, adding another day of training with the explicit goal of increasing your training volume may be valid. I talked about this in a different context when I discussed two-per-day training. And I’ll come back to this at the end of this article.

In a very real way, limiting the studies to be examined to those with a fixed weekly volume isn’t necessarily consistent with real-world training practices. But it’s the only meaningful way to analyze training frequency in isolation. So those are the studies I’ll look at.

Two Meta-Analyses and a Weird Review Article

So first let me look briefly at the two meta-analyses and one weird review type article that have been done on this topic. Two are a little bit older and one is brand spanking new (2020).

The first two are actually from the same group, the first in 2016 and the second in 2019. Part of what put me onto this topic was a question in my Facebook group which asked why the second one had drawn a different conclusion from the first and I’ll address that below.

Are Meta-Analyses Worth a Shit?

I do want to note that we might debate the practical usefulness of meta-analyses in these regards.

As I mentioned above, and you’ll see below, meta-analyses in training are invariably mixing together however many studies all of which use different training protocols with nearly zero replication.

Add to that the few studies in trained individuals and fact that much of the work is low quality and well I’m starting to feel that meta-analyses of such data is akin to mixing 10 colors of paint and deciding that they are all gray.

This isn’t like doing a meta-analysis on a drug trials where the only variable are dose, dosing frequency and duration. Within exercise science, we are trying to compare studies of vastly different design in terms of the volume of training, frequencies, intensities, etc. And as you’ll see, many of them have limited relevance to real world training to begin with.

And with that said, let me look in an overall way at the two meta-analyses and one review paper article thingie on training frequency.

The 2016 Meta-Analysis

The first meta-analysis titled Effects of Resistance Training Frequency on Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis was published in by Schoenfeld et al. in 2016 in the journal Sports Medicine. It did a fairly standard meta-analysis thing where it looked at a ton of studies (486) and then included 10 in the overall analysis since they were the only ones that met the inclusion criteria.

Note: This is exceedingly normal for meta-analysis, to find a billion related papers and only have a handful that are actually included. I’ve seen other meta-analyses find over 2000 articles and end up using like 23 of them. It’s not some type of weird cherry-picking going on here so don’t read my words as being critical. I’m simply stating what the paper did.

I’d note that of those 10 studies, only 3 of them were on trained individuals and all three were in men. And honestly these are the only studies that matter to any current debate about training so far as I’m concerned. Untrained individuals get basically the same response no matter what they do. And the question of training frequency is rarely applied to them to begin with. Beginners should do beginner training and there’s not much more to be said.

Related: How Should Beginners Train?

We’re interested here in the impact of training frequency on muscle growth in trained individuals. So we have 3 studies total with a whopping 54 subjects total to examine. One was 4 weeks, one was 8 weeks and one was 12 weeks. Yay. For now I’m not going to get into any detail on them, I’ll come back to that below.

The analysis used a statistical method called an effect size (ES) to determine if there was a material benefit to a higher frequency of training. They found that yes a higher frequency of training was marginally superior but they weren’t able to meaningfully compare 1,2 and 3 days/week. They ultimately conclude

When comparing studies that investigated training muscle groups between 1 to 3 days per week on a volume-equated basis, the current body of evidence indicates that frequencies of training two times per week promote superior hypertrophic outcomes compared to one time.

It can therefore be inferred that the major muscle groups should be trained at least twice a week to maximize muscle growth; whether training a muscle group three times per week is superior to a twice-per-week protocol remains to be determined.

They also point out that studies using only 1X/week did generate reliable growth. So it’s not as if 1X/week training doesn’t work. It simply gave LESS growth than a higher frequency when volume was matched. This would seem to support the model above where, above some certain per-workout volume, more sets are “wasted” and it’s better to distribute them into at least two weekly workouts.

Note again, these whopping 3 studies were in men only.

Ok, so that seems simple enough. Now let’s look at the 2019 followup.

The 2019 Meta-Analysis

The followup paper by the same authors was titled How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency and was published in the Journal of Sports Science.

If you’re wondering why they did the update, well there are two reasons. The first is that researchers do this all the time, just add to a previous study to pump up their paper count. Hell, I’ve seen researchers write essentially the same review paper in the same year in multiple journals so this is quite normal. In this case, there had been a number of new studies on the topic of training frequency in trained individuals since the original meta-analysis so it was worth re-examining the data.

The inclusion criteria were also a little bit different and one of the studies from the 2016 paper (Ribiero et al. in elite bodybuilders) was not included in this once since it was only 4 weeks long and I won’t it include it below.

When all was said and done, they examined 975 papers (double the first paper) and ended up with 25 total studies. Of these 10 were listed as being in trained individuals. I say listed as the meta-analysis lists one paper as being on trained individuals while the paper itself says they were untrained, trained, and then detrained.

They used the same statistical method of effect sizes (ES) to compare studies and did some sub-analyses, looking at sub-sets of the research I’ll mention momentarily. And basically in every analysis, there was no statistical difference in results for training frequency.

This was true when looking at all the studies, upper body, lower body and trained individuals separate from the rest of the studies. It all seemed to be about the same. Even when looking at non-volume equated studies, there was only a small impact of training frequency which is a bit surprising but outside of what I want to talk about.

Their overall conclusion was:

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis provides strong evidence that weekly resistance training frequency does not significantly or meaningfully impact muscle hypertrophy when volume is equated.

These findings are consistent even when adjusted for moderators such as training status and body segment (i.e., upper and lower-body). Thus, for a given volume of training, individuals can choose a weekly frequency per muscle groups based on personal preference.

With the difference in results being argued to be due to the original analysis having too few studies overall. I would note that this paper included one study with trained women (not the Barbalho et al. papers) along with men.

I mention this as there are some good fundamental physiological reasons to think that women would benefit from a higher frequency of training than men. But it hasn’t been tested very systematically at this point and I won’t speak to that for the most part.

The 2020 Review Article Thingie

And finally there is the brand spanking new paper titled The Effectiveness of Frequency-Based Resistance Training Protocols on Muscular Performance and Hypertrophy in Trained Males: A Critically Appraised Topic and please note that this is specifically in males.

Related: How Frequently Should I Train in the Weight Room?

This final paper used a method not dissimilar to the previous two studies although it was different. Specifically they did their search but required that studies be level 2 or higher based on Oxford Center of Evidence-Based Medicine 2011, Levels of Evidence. This is one of those study analysis tools. They also used the PEDro scale, another analysis tool on each study.

You know, the kinds study analysis tools Mike Israetel says don’t apply to exercise physiology….But I digress.

They also limited their search to 2014-2019 for some reason.

And in doing so they ended up with a whopping 4 studies to examine. If they did any sort of statistical analysis on the papers, I can’t find mention of it. In any case, they conclude the following:

The results from this appraisal support both the lower- and higher-frequency RT protocols for the development of muscle hypertrophy and other performance measures, such as muscular strength.

However, in 3 of the 4 studies, the groupings that were considered low frequency produced greater gains in both 1 repetition maximum bench press and 1 repetition maximum squat.4,6,29

The most important implication for practice is that well-trained RT males can benefit from a lower training frequency per week (number of sessions per week), particularly if the volume is increased

Now, they did switch from muscle size to strength at the end there but they actually concluded that a lower volume (with an increased volume per workout) might be superior and then addressed some of the potential benefits of that. They do acknowledge the very limited data set they are using.

Summary

Ok, so we have two meta-analyses and a weird review paper of sorts. The first concluded that higher frequency training was superior although the number of studies in trained individuals was a mere 3.

The second, a follow-up reversed that conclusion based on more data with 10 studies listed as trained. The third, based on a whopping 4 studies (but with higher evidence levels and quality) concluded that a lower frequency might actually be superior in some cases.

So in the aggregate, the current data set would seem to suggest that there is either no benefit to a higher frequency of training or possibly a superior result from a lower frequency. Aha! The bros were right all along.

But wait, you know I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t want to delve further into the details. Because before drawing that global conclusion I think it’s important to look at the individual studies these conclusions were based on. As I said above, we might question if mixing up 10 different studies with completely different training protocols can really give us a meaningful answer.

What I’m not saying is that we can or should cherry pick individual studies that agree with us. Rather, to build a sufficient model of anything, the specifics of the study do matter. Perhaps even moreso in exercise science where every study uses a totally different setup or set of parameters.

The Studies

To further analyze the issue, I want to look at the studies that are being cited by the three above analyses. Now, I am NOT going to go into excruciating detail as I have in other series, it would take months. Rather, I am just going to summarize them in terms of what they did and look at each briefly to see if anything can be gleaned from that.

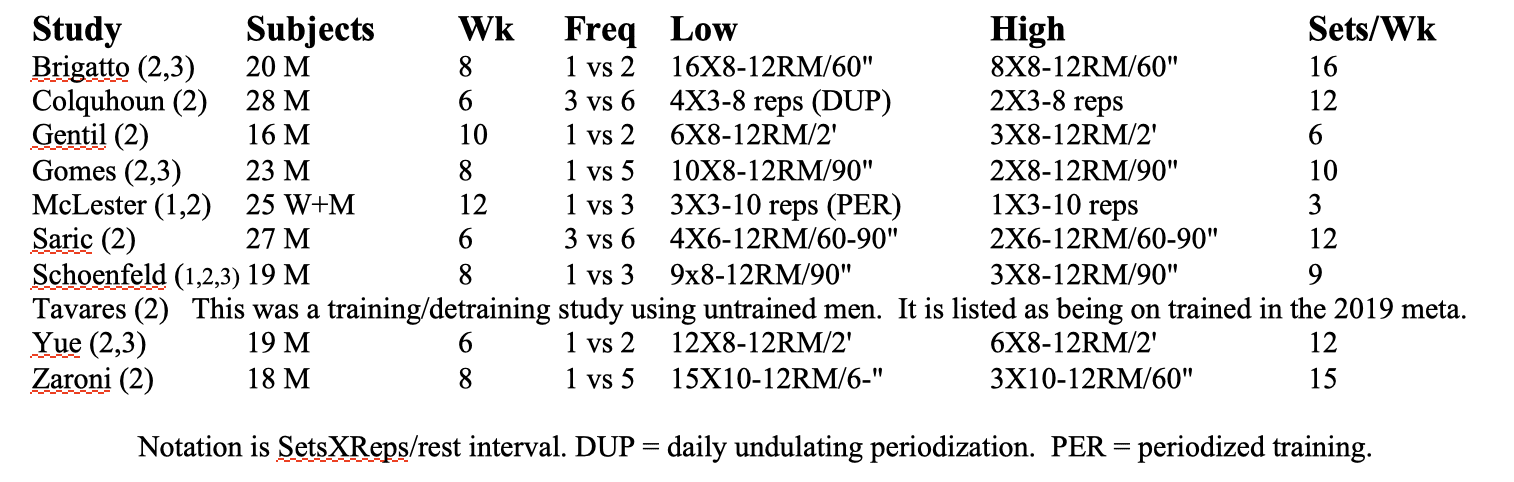

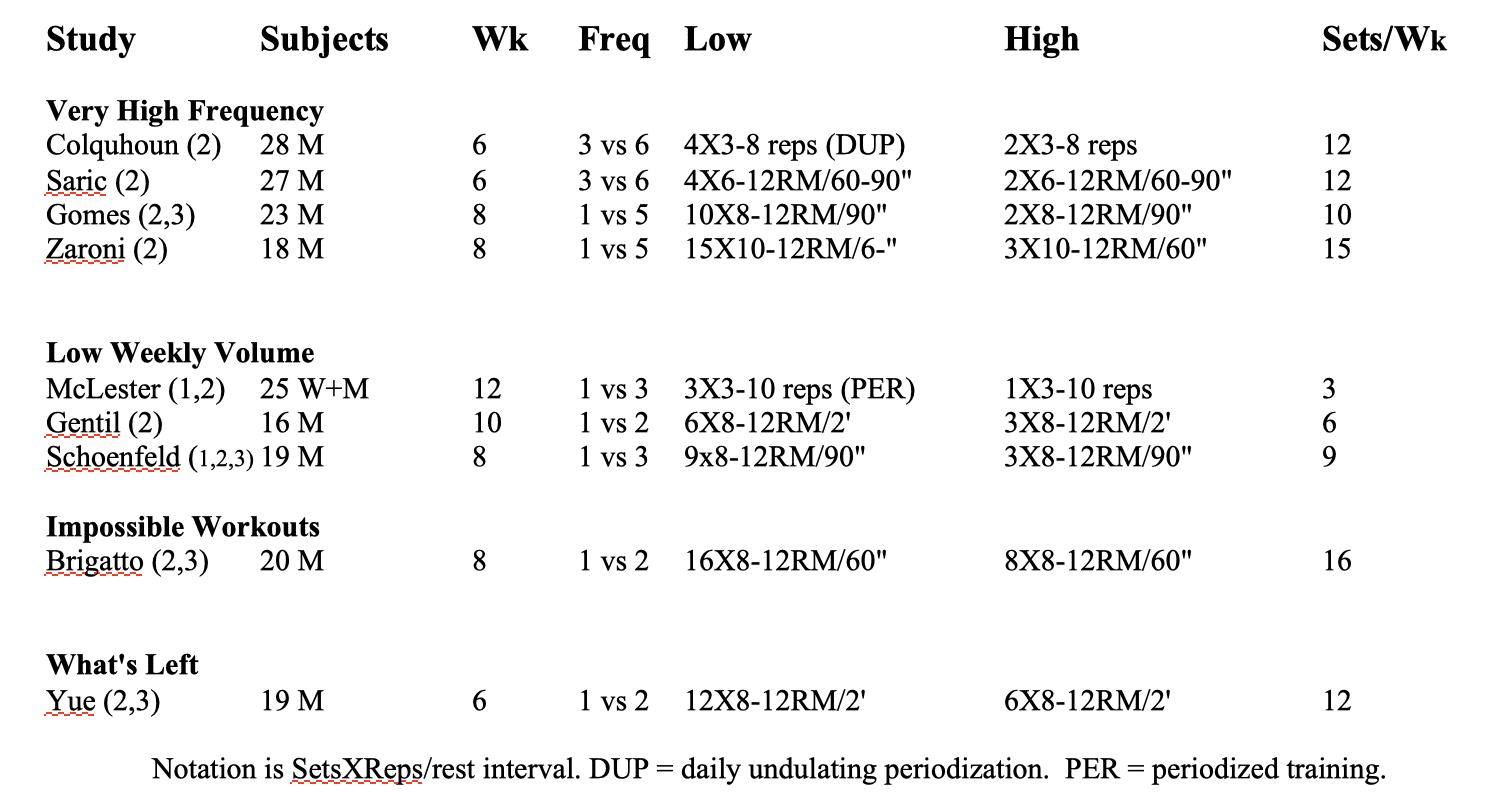

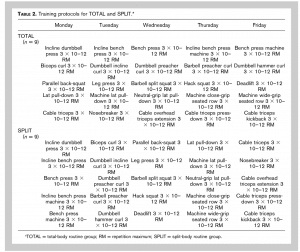

Ok, in the first chart below, I’ve listed all of the studies included in the three papers except for the Ribiero study which didn’t technically compare different per muscle training frequencies along with being only 4 weeks long.

This is just them in alphabetical order. I wish I could have hyperlinked each study but the table tool in WordPress suuuuuucks so I had to do it as an image.

In the 2019 meta-analysis, Tavares is listed as being on trained individuals. But according to the study they took untrained men, trained them and then detrained them. So I consider them untrained in terms of what is actually being discussed and won’t include it going forwards.

So we end up with 9 studies in trained individuals with a total of 195 subjects when all is said and done.

The chart contains the name of the study along with which meta-analysis (es) it appeared in. So a 1 means the 2016 paper, 2 is the 2019 paper and 3 is the 2020 paper. Only one paper, by Brad Schoenfeld et al. shows up in all three. The reason that there’s only two papers with a 1 listed is because the of the Ribiero paper being ecluded

Subjects should be self-explanatory and note that only one study included women. So any conclusion from any of this can only be considered to apply to men.

I’ve listed the duration in weeks and note that 7 of the 10 are 8 weeks or less, one is 10 weeks and one is 12 weeks. Given how slowly muscle growth occurs to begin with (along with the huge individual variability), we might question how likely the significance of a difference is.

Related: How Quickly Can I Gain Muscle?

Low frequency is the workout done for the lower frequency of training (hence it has a higher per workout volume) and high for the higher frequency of training (hence it has a lower per workout volume).

So for Gentil, for example, they either did 6 sets 1X/week or 3 sets 2X/week. I’ve also shown total weekly sets and unless I screwed up if you multiply the sets per workout times the frequency they should match the total weekly set count.

Grouping the Studies

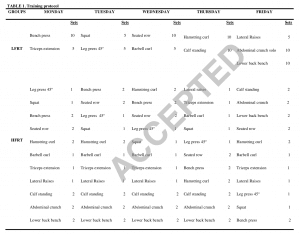

Looking at it in this format, it’s hard to discern any useful pattern so I’m going to rearrange the studies (and just take out the Tavares study entirely), grouping them by similarity in terms of structure.

Ok, so you can see four categories of studies according to my divisions. There is some overlap, for example Zaroni at 15X10-12RM on 60″ could be in the impossible workout category.

The Very High-Frequency Studies

The first is the very high frequency studies. The first two by Colquhoun and Saric both compared 3 to 6 days per week and both Gomes and Zaroni compared 1 vs. 5 days per week. And well…so what? Yes, this is comparing varying frequencies but the first two are just comparing two high frequencies to begin with and the second too very low to very high frequencies.

Let’s start with the a priori assumption that a per workout frequency of 2-3X/week is probably close to the upper limit of benefits. This was basically the conclusion of the 2016 meta-analysis and based on other indirect measures such as the duration of protein synthesis, seems reasonable.

With that assumption, you wouldn’t expect a 6 times/week frequency to be superior to 3X/week. If the 3X/week is the maximum of course a higher frequency isn’t superior.

An added issue here is that the total weekly volumes of both papers is moderate at 10-12 sets/week. In both cases that meant that the per workout volume was low (4 or 2 sets). If 18 sets/week were being done and the per workout volume were 6 vs. 3, would it have been different? I don’t know.

Nor do I think it matters since we are rarely talking about those types of high frequencies (except for folks selling E-books of course) in a practical sense.

Colquhoun et al.

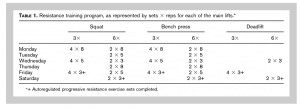

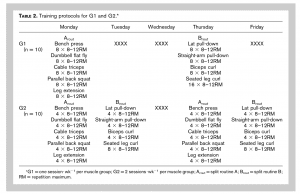

Colquhoun used a strangely structured daily undulating periodization workout, shown below.

And I can’t find any description of the actual loading beyond it being autoregulated. No mention if the sets were RM loads, or the rest interval or anything. Body composition was measured by Bodymetric for BF%. It is not mentioned if the tester was blinded but I always assume they aren’t if it’s not mentioned explicitly.

And well I’m not sure most of us would consider that a great hypertrophy set up. I mean, even if you accept that sufficient volumes of low repetition work can generate growth, nobody would consider 2X3 much of a workout.

I mean, the total weekly reps in both groups is only 64. They even state that the routine was set up to target the powerlifts and show how PL’ing totals would have changed in the results so I’m not sure this was really aimed at hypertrophy to begin with. It was a secondary outcome at best.

Saric et al.

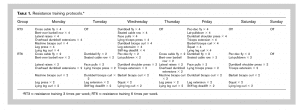

Saric used the following workout.

You can see that it’s an odd mish mash of isolation and complex movements with seemingly little logic to the workout. Why nothing but isolation for pecs but a compound for back? Face pulls is a shoulder exercise but doesn’t replace a lateral raise of overhead press.

Muscle thickness was measured for biceps, triceps, vastus lateralis and rectus femoris. No description of who took the measurements was given or if it was blinded. As above, I always assume it is not blinded if it’s not mentioned.

Sets are described as being taken to muscular failure but with only a 60-90 second rest interval between sets and 2′ between exercises.

Big picture, we have the same issue I mentioned above, with the per workout volume of all the workouts being pretty low. And I still don’t see the relevance to the usual debate which is over 1 vs. 2 or 3 times per week.

Gomes et al.

The workout done by Gomes et al. appears below. So it was either a very high volume once/week or a tiny volume 5 days/week.

Sets were performed for 8-12RM at 70-80% of 1RM and 90 seconds rest between sets. Good luck doing even 5 sets to failure on the squat with only a 90 second rest. At least in the distributed workouts, that one set of leg press or squat could be taken to limits without dying.

Body composition was done with DEXA which doesn’t have to be blinded. There was no difference in lean body mass gains, averaging 0.5 kg in the low frequency and 0.8 kg in the high frequency group, between groups.

But I still question if this is relevant to the debate as it stands for training where the old 1X/week bomb and blast is being compared to a 2-3X/week frequency. This is just comparing two extremes, neither of which I consider optimal or even relevant. It’s also at the low end of weekly volumes at only 10 sets.

Zaroni et al.

The workout appears below

Sets were done for 8-12RM with 60 seconds between sets and 2′ between exercises. And you can guess my next comment: this is another of those impossible workouts where quality will fall apart due to the short rest interval.

Multiple sets to failure on 60″….sure. And done for 15 total sets per muscle group across a single workout. At least on the split routine it’s only for one exercise which should allow slightly higher quality of training. But not by much.

15 work sets is also likely to be above any meaningful per-workout set limit although the low-quality nature might make up for that. If we assume an upper limit of 10 sets per workout beyond which more doesn’t help, that means 5 wasted sets in the low frequency group (Gomes et al. had the workout capped at 10 sets and probably avoided this). But that doesn’t mean that 8 sets done 2X/week wouldn’t have stomped them both.

Changes in muscle thickness was made for biceps, triceps and vastus lateralis. The paper only states that it was done by a trained technician but does not mention blinding. Of at least some interest, this paper found that the high frequency group was superior.

I might handwavingly argue that it was due to the weekly volume being higher. If we assume that 5 of the 15 sets were “wasted” in the low frequency group, that leaves only 10 “effective” sets, compared to the 15 “effective” sets in the low frequency group.

I still suspect that 8 sets done twice/week would have stomped both. But they didn’t do that.

Summarizing the High Frequency Studies

So that’s the 4 studies I categorized as high frequency. Two compared 3 to 6 days/week and two compared 1 to 5 days/week and I don’t think they matter that much in the big picture within the typical training frequencies that are being used.

The first two at best show that 6X/week is no better than 3X/week but I could have told you that. The third and fourth only shows that a higher frequency is superior relative to what I think is a sub-optimal frequency (where the total set count for the workout is too high). If either had compared 1, 3 and 5-times per week, that would have been much more informative.

I’d note that, as I mentioned earlier in the article some supposed “evidence based fitness professionals” who are jumping on the high-frequency bandwagon appear to have simply ignored or dismissed these studies. But I guess that’s what you have to do to “think outside the box”.

The Low Weekly Volume Studies

Next up are the low weekly volume studies. McLester used only 3 total sets/week, Gentil 6 sets/week and Schoenfeld 9 sets/week. And well….who cares, I can’t even be asked to go into the details beyond that.

Even as the training volume debates still somewhat rage (though basically everybody agrees with me now anyhow on a range of 10-20 sets) we all basically accept that a weekly volume of 10+ sets/week is needed for anything approximating maximal growth. And these studies don’t get there to begin with. So who cares?

Adding to that, the Schoenfeld study is another of those impossible/low-quality workouts with supposed sets to failure (even form failure) on 90 seconds. And I’m still waiting for a single human to send me the video of them actually doing this. And I’ll be waiting a long time.

So yeah, who cares about the results of these studies? I don’t. With very low volumes per week, not even approaching a possible optimal level, of course there is no difference. And drawing conclusions about say 16 heavy sets once/week or 8 heavy sets twice/week (or something approximating a realistic training volume in the modern era) can’t be done from these studies.

I’d note that the inclusion of these studies in the meta-analysis sort of goes to what I said above about meta-analyses seeming to mix 10 colors to end up with gray. Within the context of what trainees care about, which is frequency within a weekly training volume of 10-20 sets (or whatever), these studies are simply irrelevant.

And we might contend that they simply add irrelevant noise to any studies that do matter.

The Impossible Workout Studies

Then there is the other impossible workout study by Brigatto. Here’s what they did.

And well, hahahahahahhaa. Sure. The sets are described as 8-12 RM/to concentric muscular failure with 60″ of rest between sets and 2 minutes between exercises. Sure.

So on the low frequency, the subjects supposedly did 8 sets to failure of bench with 60 second rest before taking 2 minute rest and doing another 8 sets of flyes to failure on 60 seconds. And at the end they did 8X8-12RM on 60″ in the squat TO CONCENTRIC FAILURE and then did it on leg extension after 2 minutes.

Sure. Sure they did. And if you think I’m wrong, I am STILL waiting for the video of someone doing it. One video, no cuts or edits. Send it to me or admit that this training is impossible.

Whatever, muscle thickness was measured by Ultrasound with no mention of blinding (of course) and there were no significant differences for the different frequencies.

But I have a lot of trouble caring about this study either. The volume per week was in a range worth testing but the workouts are fundamentally impossible to complete with any sort of training quality. 8X8-12RM to concentric failure on the squat on 60 seconds? No fucking way.

Prove me wrong.

The Final Man Standing: Yue et al.

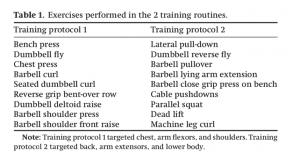

That leaves a single study out of the 9 that didn’t compare extreme frequencies, use irrelevant volumes OR use an impossible workout and that is Yue et al. Their workout appears below

Which is overall not the stupidest workout design I’ve ever seen except for one thing. Either once or twice per week, the subjects performed the above workout for either 2 or 4 sets per exercise.

So for chest it would have been 6 vs. 12 sets/week, for other movements it was a little bit lower. We might argue that the 12 sets/workout is a touch above some hypothetical per-workout limit but not by much. And the weekly volume was at least slightly above the 10+ set count.

Body composition was measured by BodPod, circumferences by tape measure and muscle thickness for vastus medialis, biceps and anteriod deltoid (?) was measured by a trained BLINDED Ultrasound tech.

Both groups gained a significant amount of fat free mass. Both groups increased vastus medialis thickness but only the high-volume/low-frequency group increased arm circumference and biceps thickness. So this slightly suggests that the lower frequency is superior.

So of all of the studies, this is about the only one even close to being relevant so far as I’m concerned. It compared a moderate volume of training, a reasonable frequency of training, used sufficient rest intervals and actually blinded the tech. A big limitation was the length of only 6 weeks and the researchers acknowledge this. As well, they mention that a huge inter-individual variability occurred, which can obscure differences.

However, one glaring issue stands out with this paper which is how the workout was implemented.

Within each workout and its volume, the subjects performed a minimum of 8-12 SELF-DETERMINED MAXIMUM REPETITIONS at 75% of max. If individuals couldn’t get to the bottom of the rep range, they were given 30 seconds of rest within the set to do so. So if they got 6 reps, they got to rest for 30 seconds and get two more.

And well, that’s kind of asinine. Now we’re getting deep into internal motivation, drive, etc. We can quibble over whether or not training to failure is good or not but at least concentric failure is an objective determinant of the set. Letting people decide when they have hit their maximum introduces another huge variable. Most stop when it gets hard, not when they get even close to failure. Watch anybody in your gym to see that I’m right.

Even that might explain the apparent superiority of the low frequency group. Assuming that most trainees were stopping the set long before failure (and based on what I’ve seen over 25 years in gyms, they were) they’d have needed more volume to “make up for it.”.

I’d also note that the leg workout was stupid. Squat, deadlift and leg curl? Good grief.

So while this is the best, and in my opinion, the only semi-relevant study in the entire set of 9, it still has the one glaring problem in terms of allowing the subjects to decide when to end the set (and a moronic leg workout) That has the potential to introduce such huge variance in effort, closeness of the sets to failure, etc.

I also suspect that with an even higher volume per week, 12 sets being close to the lower limit, the results might still be different. But the only study that used those higher volumes used an impossible workout. Sigh…

Summary

So what does that tell us? Well, that when you throw 9 studies of drastically different design together and average out the results, you conclude that frequency doesn’t matter. And maybe it’s true under those conditions. But it sure seems like the different designs and set ups of the studies make this difficult to conclude.

You have 4 super high frequency studies (2 of which compared very low to very high), 3 studies with insufficient volumes, 1 more with an impossible workout and then one that is actually reasonable but which let the lifters decided when to end the set. And I don’t think you can draw a particularly good conclusion from that. I’m not sure you can draw any conclusion from it.

Before continuing, let me look at the review paper/article thingie briefly.

When/Why is Low-Frequency Better?

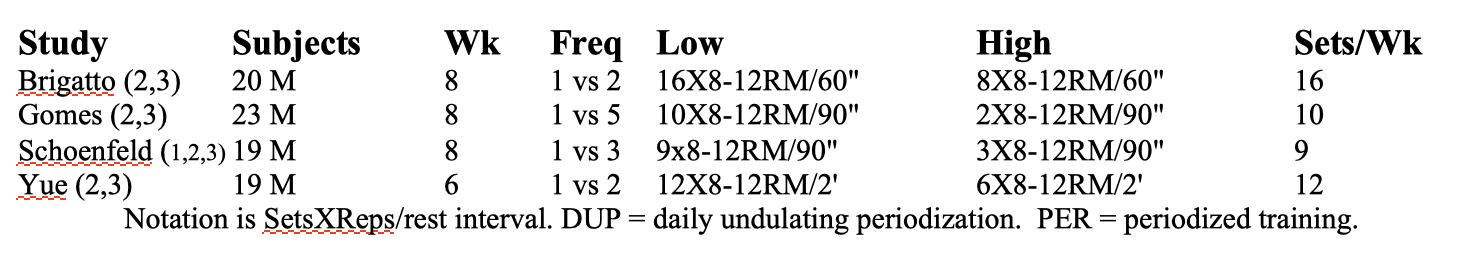

But you might be wondering, what about that opposite conclusion from the weird article thingie, the one arguing that lower frequency was superior. Well let’s look at the 4 studies it was looking at by themselves. I’ve repeated their specifics below.

Of those 4 they state that Gomes, Schoenfeld and Yue all found greater 1RM improvements in the lower frequency group. What were the commonalities? Well in all three the total weekly set counts were fairly low, 10, 9 and 12 sets/week respectively.

That means that with the higher frequency those low volumes were incredibly distributed. Gomes’ subjects did 2 sets 5X/week vs 10 sets 1X/week. Schoenfeld did 3 sets 3X/week vs 9 sets 1X/week. Yue did 6 sets 2X/week vs 12 sets 1X/week.

In the first two studies it’s easy to see what was going on. In the same way that there is likely some upper limit volume to stimulating growth (or strength increases, to change topics), there is assuredly a point where too little volume has no real effect. Or certainly an effect that is sub-optimal.

In a trained individual, unless they were heavy, high-quality absolutely limit sets, I wouldn’t expect 3 sets to get it done. And both Gomes and Schoenfeld were not that kind of training. Because you can’t do quality training on a short rest interval.

Related: How Long Should I Rest Between Sets?

The Yue study is a bit harder to examine in that context. The volumes were higher and the RI was high enough to make the training be quality. It was also the shortest study, perhaps too short for any real differences to show up. And yet the 12 sets still showed a superior result to the 6 sets. In this case, I’d have expected the opposite.

I suppose the handwaving argument would be that they tested 1RM squat. And squat was only one of the lower body exercises. So it would have been done for 6 sets 1X/week and 3 sets 2X/week. And that probably does explain it.

With the distributed volume, squatting for 3 sets just wasn’t enough for an optimal stimulus in either workout. We’ve also got the issue of the subjects being allowed to decide when to stop the set which is just utterly asinine within the context of research. At least 6 half-assed set of squats might be a training stimulus. 3 half-assed sets of squats twice a week won’t be.

And that’s what I think explains that third claim that a lower volume is superior. And I would say it’s absolutely true for lower weekly volumes of training. The problem with distributed training is that it has the potential to make the per-workout volume too low to be meaningful.

And course the single study using a much higher weekly volume of 16 sets did not find support for the lower frequency. I mean, yeah, the training was short RI low quality crap to begin with but 16 total sets is far beyond any per workout limit on stimulating adaptation. Splitting that volume into two shorter workouts makes perfect sense.

While the above mainly focused on strength, they do mention hypertrophy but here there’s no real pattern. Brigatto and Gomes found no different in hypertrophy, Schoenfeld suggested a higher frequency was superior and Yue suggested lower frequency was better.

Which is a long way of saying that their conclusion is probably valid if someone is doing lower weekly volumes of training. There, distributing volume may reduce the per-workout stimulus to such a low level that it’s not worthwhile. In that situation, doing all of the volume at a lower frequency is likely to give better gains.

But once volumes get past a certain point, distributing volume is likely to be superior. Simply because you can keep each workout below whatever anabolic limit/optimal stimulus threshold that may exist.

So What is the Impact of Training Frequency on Muscle Growth?

So what can we conclude from this? Well, I’m not entire sure. My point of all of this is that, while the conclusions are the conclusions, I don’t find the data set from which they are coming terribly compelling or meaningful.

At least not in terms of drawing good conclusions given more real-world training practices and what the typical debates in the fitness world are really about.

Nobody seeking maximum size who cares about frequency debate is doing less than 10 sets/week and most are probably doing more. So studies comparing 3 or 6 or 9 sets/week just don’t apply here.

I wouldn’t expect any significant difference when the set count is too low. And as the third article thingie, in some cases, a lower frequency might be BETTER when the volume is too low. Which actually makes logical sense if you assume that the per workout volume can be too low.

Workouts of supposed 8-12 RM to failure on short rest periods are fundamentally impossible and until someone sends me a video showing it can be done, I won’t change my mind. Nobody trains like that who trains hard because it can’t be done.

I’ll address this more when/if I finally update my volume series with the new work.

As well trying to build a model of different training frequencies when no study has examined more than 2 frequencies at once is difficult. Once you get past 3 times/week it’s clear that there is no benefit. Comparing 1X/week to 5X/week prevents you from knowing if a more realistic intermediate frequency might be superior. I think you get my point.

And all of this is a long way of arguing that I think the current repeated conclusion that “training frequency doesn’t impact on muscle growth” isn’t quite as clear cut as many want to think. One early meta-said it was, a second said it wasn’t, and a third paper for a lower frequency being optimal, at least contextually.

Basically, I think we are currently lacking well designed research to properly examine the question that we want addressed. Which is a useless statement (all research is good and bad and has drawbacks and blah blah blah) without being constructive. So I’ll be constructive now.

The Research We Need

To me, here’s the study that would need to be done to draw any useful conclusions relative to current training practices, along these lines anyhow:

Take two or three groups of trained individuals. Now set weekly training volume in what is likely to be an optimal range. Let’s say its 18 sets/week or thereabouts. Keep it heavy, define set termination as concentric failure and have it supervised.

Give a sufficient rest interval of at least 2 minutes. None of this 60″ or even 90″ bullshit. You need at least 2 minutes between sets to keep quality up/for optimal hypertrophy results. Why anybody is still doing these high volume studies on short rest intervals in the late 2000’s is beyond me. Why anybody believes they are even possible is beyond me. 8X10RM on 60″ on squats? Bullshit.

Importantly you have to set a per workout volume cap of maybe 6-10 total heavy work sets per muscle group. Even if we don’t know for sure where the per set maximum for an anabolic stimulus is, it’s likely in that range. Just go back to Wernbom with the 40-70 reps/workout and you get right in that range anyhow.

Now divide your 18 sets/week volume up. With the assumption that 10 sets is the per workout maximum, there’s no purpose in really studying a 1X/week frequency. I mean you can but it’s well above our hypothetical per-workout maximum and I’d predict ahead of time it will get poorer results due to so many of the sets being “wasted”.

Yes, I know many bodybuilders still train like this but nobody is doing 18 truly heavy RM sets to failure per workout because it can’t be done. Because I’ve watched those guys in my gym. Are they faffing about for 18-20 sets? Yeah. Could I drop any one of them in a few all out sets? Yup. I know because I’ve done it.

Sure, if they are training to 3 reps in reserve, the workout can be done. And might even be meaningful but only because you’re making up for lower quality sets with a ton of volume.

So immediately you might as well start at 2X/week which would yield 9 hard sets per workout. This is in the likely per-workout optimum range. And I would predict that it will destroy 1X/week in terms of gains. Yes, 1X/week will still grow because it’s still 10 effective sets per week or whatever. But 2X/week will grow better because you’re getting 9 effective sets twice/week instead of 10 effective sets and 8 wasted sets once/week.

I suspect most reading this will agree with me.

The interesting question will be whether or not 6 heavy sets done 3X/week will be superior to 9 sets done 2X/week. Both are in that 6-10 per workout range just at different ranges of it. Both would allow high-quality training with a sufficient rest interval and I wouldn’t suspect a big difference. Certainly not one that would possibly show up over short periods.

Oh yeah, make the study at least 12 weeks long. And, for god’s sake include some women as there are likely to be systematic sex based differences in this with women being far more likely to get superior results with a slightly higher frequency of training.

That’s the research we need to really nail this topic down and until it’s done I think mixing up the studies to date gives us a gray paint conclusion of no meaning. The studies are either too low volume, compare extreme irrelevant frequencies or utilize impossible workouts. I don’t see any of this as relevant to the current debates or arguments to begin with.

And until that research appears, let me wrap-up this monstrosity by actually giving some sort of practical recommendations on training frequency.

Revised Recommendations on Training Frequency

I have written about training frequency in the past and still maintain that, under most conditions, training each muscle group twice weekly or once every 5th day will be optimal. For women, maybe a little but more frequently.

Related: How Often Should I Train to Grow?

Mind you, I was always basing that on Wernbom’s original analysis and assumed in that recommendation was a certain per workout volume of heavy sets. The analysis that it is popular to shit on but we sure seem to becoming back to it or some close cousin of it more often than not.

But now it sounds like I’m ignoring the research. Well, sort of and sort of not. Honestly, I don’t find the aggregation of all of these different studies meaningful. They are too different (a problem with meta-analyses in general) and I don’t think the data set really tests what we want it to test within the context of modern day training practices or arguments.

But let’s see if I can build a model of training that actually does include the research that these meta-analyses examined. Basically, let me revise the frequency recommendations I’ve been thumping for, oh, about 15 years now.

Building a New Training Frequency Model

Because inasmuch as the studies done are the studies done, I think the primary factor going into whether or not a given frequency may or may not be superior will depend on two assumptions (both of which seem to be generally accepted at this point but which could be overturned by direct data):

- There is an optimal per set workout volume of roughly 6-10 heavy sets with a sufficient rest interval (at least 2 minutes). Anything above 10 sets (and possibly less) is just junk volume. It generates no further stimulus for growth but does cut into recovery.

- The only way more than 10 sets/workout is useful is if you cut the rest period to such a point that the quality of training is drastically reduced and you are using volume to make up for a lack of quality. Or if you wanted to just faff about doing repeat warm-up sets on a 10 minute rest as in the Haun et al. study Mike Israetel was involved with. Sets of 10 with 4 in the tank? Sure, do 30 of them a week. You probably need to because every one of them is worth like 1/8th of a heavy set.

With those assumptions we can then determine what might be possible frequency ranges or optimal frequencies based on those two assumptions along with how much weekly volume is being done.

Low Training Volume: 6-10 sets or less per week

First let me look at a low volume of training: 6-10 sets or less per week. This is already below the per workout maximum threshold and it probably won’t make a difference whether you train 1X/week or 2X/week. Assuming all sets are quality sets, there won’t be any waste if they are done only once/week.

In fact, depending on how low your weekly volume, training 1X/week might be superior to a higher frequency. If you’re only doing 6 heavy sets per week, you’ll probably get better results by training once/week instead of twice/week because the 3 sets may be too little of a per workout volume to be optimal. This might be untrue if you know how to push and go to true limit failure on every set.

Since I wouldn’t ever use this low of a weekly volume outside of maintenance periods (and beginners, who are not the topic of this article) in the first place, you’ll never see me recommend this. Moving on.

Related: What’s the Best Way to Begin Training?

Medium Volume Training: 10-20 sets per week

But let’s say you push your weekly training volume up to 10-20 hard sets/week. Clearly this is above the 10 set/workout maximum at its start. Which means that, given our assumptions, training 1X/week cannot be optimal as it would lead to as many as 10 wasted sets.

In this case a minimum training frequency would be 2X/week which would be 10 heavy sets/workout. This is at the upper limit of the per-limit maximum but still fits it without there being any “wasted” sets.

It might also be possible to increase this to 3X/week and do ~7 work sets/workout. This is still within the optimal per workout set range. Would this be better than 10 sets twice/week? Who knows. It’s probably a wash in the big picture.

Moving to 4x/week would mean cutting the per-workout volume to only 5 work sets. This is technically below the per-workout optimum value and might start to give less optimal results. Certainly we get into other variables here, cumulative fatigue and overlapping gene expression. So this might be workable and it might not be. It’s right on the cusp.

This actually gets into other issues with connective tissue recovery and injury but that’s not the topic of this article.

There would be zero reason to go beyond that as it would reduce the per workout volume too low to be an optimal stimulus. And literally no research supports it despite the many on Youtubes saying they “got great results from it”.

High Volume Training: 20+ sets per week

Now let’s say you push it up past 20 sets/week for some reason. I mean, the research base doesn’t support it and everybody has basically come back to agree with my 10-20 sets/week recommendation after spending a year and a half defending bullshit.

But let’s say you want to “think outside the box”. Let’s say you want to do 25 sets per week for some reason.

Training 1x/week is out as 25 hard sets could not be completed to begin with and would be far above the per workout maximum with as many as 15 potentially wasted sets per workout.

Training 2X/week would not be optimal either as you’d still be at 12 hard sets, wasting perhaps 2 sets by being above the maximum per-workout cap. If your workout quality was low with short rest intervals, this might be ok but only because 12 crappy sets probably equals 8 hard sets to begin with.

At 3X/week you’d be at ~8 sets/workout which brings you into the optimal per workout range. So this might very well be the minimum optimal frequency at this volume. A short-term high volume specialization phase might be set up this way.

And if you want to 4X/week, that’d be 6 sets/workout which is at the low end of optimal. And then, of course, your connective tissue falls off and you get tendinitis anyhow. Unless you use a lot of intensity cycling, high-frequency high-intensity training tends to be pretty self-limiting because you invariably get hurt.

Related: What is Bulgarian Training?

Since I wouldn’t ever recommend training volumes at this level, you’ll also never see me recommend particularly high training frequencies. Yes, I currently train a female powerlifter and she currently trains each lift 3X/week. But this is performance training and I mentioned that women often benefit from a higher frequency. And her per workout volumes are not that high.

My Revised Frequency Recommendations

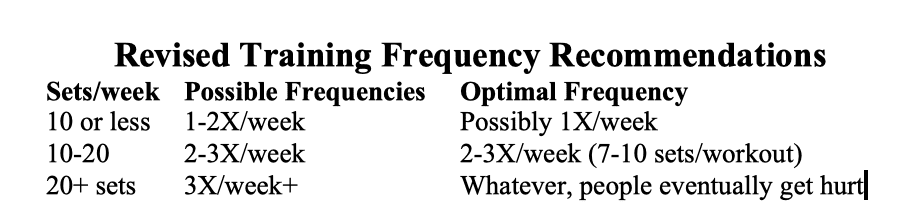

So let’s sum that up, what I would argue are optimal frequency recommendations based on the data set (such as it is) and a couple of (what I consider) reasonable assumptions:

With women almost universally being at the higher end of frequency for reasons that will all eventually be explained in eventually forthcoming The Women’s Book Vol 2 (don’t ask me when, I don’t know).

Of course, since I will continue to mostly recommend an optimal volume of 10-20 sets and since most people prefer split routines and can’t train 6 days/week, that means I’ll keep recommending an average training frequency of 2X/week (once every 5th day in some cases). Which I think is a reasonable conclusion based on the data set available.

When and if someone actually does some research similar to what I described above in terms of weekly volumes, reasonable rest intervals, heavy sets and training frequencies of relevance, I’ll be happy to change my recommendations.

Facebook Comments