Continuing from Part 2 where I defined talent and presented what I call the Work/Talent Matrix I want to move into some seemingly unrelated issue that tie into this topic. First let me go off on a bit of a tangent about how people seem to parse the question “Can hard work beat talent?” when it comes up.

Table of Contents

Don’t Stop Believin’

There are certain concepts in fitness and sports that, no matter how clearly I try to explain them, someone will misinterpret it. This is one of them. The mere idea that there might be genetic limits to someone’s performance, that no amount of hard work might ever get them to their goal is just met with a lot of resistance.

I’m not sure it just comes down to reading comprehension, though. Rather, I think it has to do with most people’s deep seated psychological desire for what I’m saying not to be true. Deep down they want to believe that if they just put in enough work for enough time they can get anywhere they want without limit. It’s a very Puritan work ethic thing (very popular in America) and is promoted by a lot of media.

Rocky movies, Disney movies, most sports movies where all it takes is a 5 minute training montage to a motivational song to become great at something.

Throw in an inscrutable master, a trick move and you can turn anybody into a world beater.

Make no mistake, I wish it were true too. In my 20’s I was the classic workhorse driving myself with as much training as I could stand. I spent most of my 20’s overtraining myself into the ground. And repeated that pattern often because it’s impossible to coach yourself.

In any case, people seem to respond really negative to the idea that there is any sort of genetic or in-built limit because they simply don’t want to believe it. People don’t want to believe the realities. Again, neither do I. But what I want to be true and what is true aren’t always the same.

And when I write articles about genetic limits, people seem to interpret them in one of two ways.

Two Responses to the Idea of Genetic Limits

The first is that I’m just trying to piss on their parade or “hold them back” by telling them that they can’t be what they wish they could. And trust me when I say that nothing could be further from the truth. I truly wish everyone out there had the genetic potential and work ethic to be the best.

To be 250 pounds of solid cut muscle without steroids. To squat 1000 lbs. To set world records and reach the top. I do. I also want a pony that shits gold and for unicorns to exist. Because what I want to be true and what is true aren’t the same.

I also think it’s important for people to have realistic expectations on what they might achieve. Too much of this industry is based on making false promises, using the images of drug built physiques to push books, training ideas or supplements. And they don’t work. Even as drug using bodybuilders continue to get bigger, naturals remain the same size. And that’s because human genetic limits haven’t changed.

The second idea people come up with is that my discussion of there being a limit means that they shouldn’t bother trying. It’s a weird either/or psychology that people have. Either you’re first or you’re last, either you cant accomplish every goal you set out without limitations or you shouldn’t bother even trying. And this isn’t what I’m saying at all.

As I stated explicitly when I talked about genetic muscular potential, talking about genetic limits is in one sense critically important and in another completely irrelevant. It’s critically important to know that there are in fact limits that you will eventually reach naturally. But until we can do genetic testing, nobody knows ahead of time how far you might get.

If you’re a cyclist and you start training, you might be the next Tour De France competitor or you might never make it to or past Category 3. As a bodybuilder, you might have the potential to get to 200 pounds of freaky lean muscle mass or you may never be more than 165 lbs ripped. You won’t know until you put in the time and find out.

At the same time, I can say with some certainty that the average male trainee might gain 40 lbs of muscle over a career if they are lucky and do everything right. A woman might gain half of that. So if you’re currently 140 lbs, I can say with some certainty that you won’t get to 200 lbs lean. Other models using height can be predictive as well.

And while there are always exceptions to this, statistically speaking you are not likely to be one of those exceptions because that’s not what the word “exception” means. Most people in any activity will only achieve average performance levels because that’s what the word “average” means. But you might get lucky, maybe you will be an exception. You won’t know until you try.

Basically, the only real point of talking about limits is as a reality check. To recognize that you do have a limit (even if you don’t know where it is) and that once you get there, you’re not going past it. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t work like the dickens to get there or see what those limits are. And how do you know where those limits might be? Let’s talk about asymptotes.

Asymwhats?

For those of you who didn’t pay attention to or simply sucked at high-school or college math, an asymptote is a line that can be approached indefinitely closely but that you can never reach or cross. In college my nerd friends and I developed the concept of the humor asymptote. It occurs when a joke is finitely close to being funny but doesn’t quite get there. I tell a lot of those.

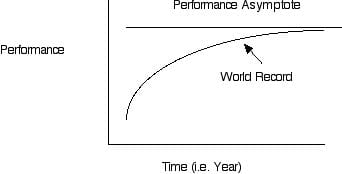

Many things work on asymptotes. World records are one of them and this is an example I bring up whenever people try to argue that “there is no limit to human performance”. Because invariably when you graph performance over time you get a curve that looks something like the following:

.

So, for example, if you graph the men’s marathon world record over the years you invariably see a rapid improvement early on with incremental improvements over time approaching the theoretical line.

Where that line actually falls is often to debate but clearly there is some upper limit. And you can usually get a pretty good idea of where that line is based on real world performances over time. Consider for example that the world records in track and field have been stagnant since the late 80’s. The last big jump was for the Germans in track and field and that was all drug driven.

And this holds true for most sports. You see rapid improvements early in sports competition which start to level out and level out, making only miniscule improvements over years or decades.

The only exception is in sports where massive equipment improvements cause performance to jump. This happened in ice speed skating with the invention of the Klap skate and in swimming with suits that were later banned. I have detailed how fixing an equipment issue with my inline skates improved my performance by 30%. But that’s an exception.

The 100m Sprint

As an example, consider the 100m sprint where, in all likelihood nobody will ever run a sub 9 second race. I am basing this on the rate of progress of the world record. In 1988, Ben Johnson ran 9.79 and it’s thought he might have gone faster if he hadn’t slowed at the end.

In 2009, Usain Bolt went 9.58. So in 20 years, the best time in the event dropped by 0.21 seconds or roughly 0.01 seconds per year. Ten years later this record still stands so zero progress has been made since then. Here there is clearly a physical limit to how fast a given distance can be covered. There is a limit to acceleration and top speed that will only be surpassed when humans become beings of pure energy and finish the race a week before it started.

Powerlifting

A lot has been made about the seemingly constant improvement in powerlifting and that’s true if you’re looking at geared events and federations passing progressively shittier lifts. But now go look at the RAW tested federations where the records in the open classes are fairly stagnant.

Yes, tiny improvements are occurring and occasionally you find a freak lifter like Ray Williams who just lifts the world. But that’s more to do with more athletes coming into the sport. Certainly in the master’s and women’s classes records are continuing to drop but that’s due to unprecedented increases in athletes entering those categories.

For everyone else? It’s a lot of nothing. Despite all this fancy new technology and bands and chains, the numbers aren’t moving much. That’s because human genetics haven’t changed.

Natural Bodybuilding

The same can be seen in natural bodybuilding and you can prove this to yourself by going to a show. The biggest divisions are the middle weights at like 165 lbs with only a few guys topping out near 200 lbs lean. Yes, they exist but like powerlifting that’s just due to some freakshow athletes entering the sport.

Despite all the new developments in training and nutrition, the average contest weights haven’t really gone up at all. Because human genetics haven’t changed.

In the pro ranks, the story is different. Whereas Arnold competed somewhere between 220-240 (depending on your source) there are current pros carrying 300+ lbs ripped. And it’s not due to hydrolyzed whey protein.

The point being that asymptotes exist for all sports performance. Most records are stagnant with few exceptions and that’s all they are. It’s usually due to equipment improvements or the occasional freak show athlete. Or drugs. But that’s about it.

Now Let’s Talk About You

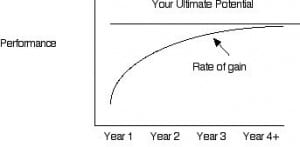

For any given individual, when we are talking about physiological capacities, there is going to be a similar asymptote that exists. And folks will approach that line similarly assuming proper training is being performed. Obviously if you train like an idiot, you can train for literally years and not approach that limit.

So when someone starts training, their gains are rapid and exciting. In the first year they may see just a huge improvement in their strength or muscle mass or endurance or what have you. Going into year two, those gains will slow down.

If someone is lucky they might improve by half as much as they did in year 2. And by the time they are in year 3, those gains have been cut in half again. Even if we argue that they are only at 90% of their ultimate potential by year three, it may take years to get that last 10%.

So a natural male bodybuilder, if they are lucky might gain 20-25 lbs of muscle in the first year. That might drop to 10-12 in the second year and another 6 in the third year. And they may spend the next several years grinding and scraping for even another pound or two. And nothing they can do except take steroids will change that.

For strength activities, a new lifter may be adding 5-10 pounds per workout for the first several months of training. By the time they are in their second year, they might work for a month to add that same amount. High level natural powerlifters may work for 12-16 weeks to add 5 lbs to their lifts. An Olympic lifter I talked to year ago told me that his coach aimed for a 1-3kg (2-6 lbs) improvement at the end of a 16 week training cycle. Three of those in a year gets you 3-9kg (6-20 lbs).

Note: all of the above really only applies to adults beginning a new activity. In kids you often see a different pattern because a lot of things aren’t trainable until after puberty. A kid who starts a sport when they are 8 will see some improvement for some time period and then, when they hit puberty, they will see more years of improvement until they come up against their own genetic limits. Exceptions would be a sport like women’s gymnastics where puberty is usually the end of their career. Since I doubt that many 11 year olds read my site, I’ll stick to talk about adults.

Because for adults the above pattern is reality. By about year three or four of proper training, you’ll be approaching your inbuilt physiological limits assuming your training up to that time wasn’t idiotic. By that I mean that if you train stupidly for 4 years, you might still get “beginner gains” in year 5. And then you’ll see the same pattern of improvement for a few years and you’ll plateau.

But assuming proper nutrition and training are in place and that you put in the effort, you can redraw my graphic above with changed headings. And this will represent how most people improve in a given activity.

.

And the real-world consequence of this reality is this: if you’re not already pretty close to the top people in your sport by the 3-4 year mark, realistically you’re never getting there. So let’s say that you have 10% more improvement to make even if it will take years. If you’re 20% behind the top guys in your sport (or 20% away from your goal), you’ll never get there because the gains you’ll be making are miniscule (now we might question whether it’s worth bothering).

Going back to my other examples. Lance Armstrong was winning races when he was 16 and Steve Prefontaine set high school running records when he was 14-15 that stood for decades. Ed Coan said he pulled 405 his first time in the gym and I recall Benedict Magnusson stating the same. Both went on to pull over 1000 lbs. Make no mistake, all four of these athletes put in years to reach their final potential.

That was the point I tried to make in the first two parts of this series: athletes who reach the top almost invariably start at a higher level (i.e. have some inbuilt talent), combine that with years of hard work (and usually an inbuilt ability to adapt to training) and that’s how they reach the top. If you don’t start out at a similarly high level or aren’t in that small percentage of hyper responders, you won’t get there.

The MFW Hardhead

Probably 15 years ago, I had this very argument with someone who steadfastly believed that there were “no genetic limits”. Now he had been lifting about 10 years and his squat was something like 500 lbs. Make no mistake this is a good squat, a big squat and a squat most would love to have. And the record in his class was like 800 lbs or some craziness.

So I asked him if, after 10 years of hard training, he as only at 500 lbs, when did he expect to hit 800 lbs? What about 1000 lbs? If there are no limits, when will he get to either value.

Let’s just say that I got no coherent answer from him. The simple fact is that by the time you’re spending a year to add maybe 30 lbs to your lifts, the odds of adding those last 300 lbs is pretty slim. By which I mean unlikely to ever happen. Eventually age alone catches up with you and you’re fighting just to avoid losing ground.

By the time you’re working for an entire year to add 1% to your results the simple fact is that if you’re not at 99% of the best, you’re not getting there. Ever.

You Can Always Improve

Which is not to say that people will stop improving past the 3-4 year mark of proper training. Certainly in a physiological sense, the improvements are likely to be very small. And here we might debate whether the effort required to gain microscopic gains are worth it. But that’s a different question that only any individual trainee can answer for themselves.

One exception to this is in activities with major technical demands. With regular practice, technique can keep getting better/more efficient. And occasionally you may see improvements that aren’t quite what the curve above would predict. Because in those very technical activities, often a technical breakthrough can generate a major jump in improvement.

I saw this a lot when I was pursuing ice speed skating in Salt Lake City. After 4 years of grinding work where I was making progress I had a huge technical improvement in my corners which more or less put me back on the beginner curve in terms of improvements for the next year. But this is very much an exception, one that occurs in excruciatingly technical sports but not so much elsewhere. You won’t see it in running or cycling since there’s not real technical breakthrough to have.

Mind you, sports and performance are not just determined by physiological factors and competitive athletes often continue improving their results past the four year mark through improved tactics, competing smarter or with better equipment. Of course, this rarely jumps them far outside of their current competitive group. But a Category 3 cyclist who learns how to race better tactically may suddenly jump in the standings without developing an iota of physiological fitness.

The series finishes in Can Hard Work Beat Talent Part 4.

Similar Posts:

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent: Part 4

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent: Part 2

- Can Hard Work Beat Talent?

- Four Models for Genetic Muscular Potential

- Success Leaves Clues

So what your telling me is that because i am 5’10” I need to give up my dream of playing center in the NBA? damn

Lyle,

Great part 3 to this thought-provoking series!!!!

This part [Lance Armstrong was already winning races when he was 16, Steve Prefontaine set some high school running records when he was 14-15 that (I believe) stand to this day. I seem to recall a story, perhaps false, that Benedict Magnusson (one of two men to clear 1000 pounds in the deadlift) pulled 405 lbs his first workout] reminded me of this (can’t recall the source…), which also helps to put things in perspective…

“At 18 years old, Carl Lewis ran a 9.3 second hundred yard dash, which would be the equivalent of a 10.10 second hundred meter dash. At the peak of his career, at age 27, he had improved to 9.92 seconds. He trained ten years full time at a couple of events to improve his speed by about 5.5 feet over a ten second run.”

One can easily imagine that Lewis had access to some of the top ideas, protocols (huh, hum, performance enhancement “supplements”) and minds in the field, worked his butt off and yet, it’s interesting to view his ‘improvements’ through the matrix you proposed…

Being relatively limited in my talent and also having driven myself to the ground at various times (thanks to Rocky, sports movies and Disney; yes, that would probably sum it up well), I’ve decided in the last 4 or 5 years to follow the wise words of Bill Pearl, as told to me by Ken O’Neil: Pass a certain age, you have to start thinking of maintenance more than performance. 🙂

Great article, as usual!

ouch

In cycling, when EPO came out all the times jumped dramatically. They have not since gone down. First they were just testing for total hemocrit %, which doesn’t tell you whether the person is using EPO. They used an arbitrary cutoff of 50%. “Surprisingly” every athlete seems to have just below 50% levels of RBC in the Tour de France, even though they were not like that years ago and it is extremely uncommon to have such a RBC naturally. Also “surprisingly” everyone competing in TDF has the regulations maximum testosterone to epitestosterone ratio, even though the ratio (something like 6:1 I cant remember) never usually occurs in normal people. So the athletes top up their levels right to the legal limit.

For the cyclist who wins and gets a multimillion dollar house in Barcelona, they can pay for anything. When better testing identifying EPO came around, blood doping was better. Also, these cyclists pump their crit above 50%, then if they get called for testing, they have their own doc in their trailer to hydrate them through IV and lower crit levels back down to 50. They get 20 minutes to do this before the testing.