One of the primary factors that separate women and men is the presence of the menstrual cycle, the roughly 28 day cycle during which her primary sex hormones estrogen and progesterone change in a fairly “standard” pattern. During this time, nearly every aspect of her physiology changes. Specific to today’s article I want to look at the impact of the menstrual cycle on energy balance (i.e. calorie intake vs. calorie expenditure). In doing so I will be primarily looking at the following paper.

Table of Contents

Women and Body Composition

As I discuss in extreme detail in The Women’s Book women get the short of the end of the stick when it comes to body composition. Their bodies fight back harder, they lose both weight and fat slower (even given an identical intervention), they tend to gain fat more easily, they gain muscle more slowly, etc. Then again, they do get that whole multiple orgasm thing so there is at least some good that comes along with the bad.

In any case, there are a lot of potential reasons for things to be this way and it’s been theorized that the importance of women in keeping humanity alive (by raising children) during famines is a huge part of the gender discrepancy. For example, women are more likely to be in the super-obese category and far more likely to survive famines than men. While even men’s bodies fight back, the simple fact is that women’s pretty much always fight back more.

Of course, the biggest potential impact on all of this is hormones which differ drastically between men and women. It’s been known for a while that women’s fuel utilization changes during their menstrual cycle, as does appetite and potentially energy expenditure.

In this vein, it’s been suggested that dieting (and training) might or should be modified during the menstrual cycle to match up physiologically with what is going on in a woman’s body. I’ll come back to this a bit below.

That’s what today’s research review is about, a look at how things such as energy intake, appetite, energy expenditure and body weight change throughout a woman’s cycle, as well the impact of birth control is briefly examined along with some issues related to PMS and food cravings.

And Overview of the Menstrual Cycle

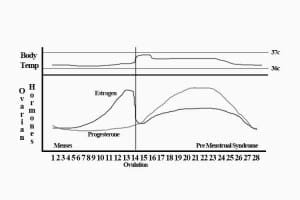

The first section of the paper is simply a review of the hormonal changes which occur during a normal menstrual cycle. Although there is variability, the typical woman’s full cycle is 28 days (this is an average) which is typically divided up into 4 distinct phases. With menstruation taken as day 1, we can define early follicular phase (day 1-4), late follicular (days 5-11), periovulation (day 12-15), and luteal phase (days 16-28).

A number of hormones change during the cycle but the two that I’m going to focus on are estrogen and progesterone. During the early follicular phase, both estrogen and progesterone are relatively low. Estrogen (estradiol in the graphic below) shows a peak in the late follicular phase followed by a drop. Progesterone starts a slow increase through ovulation and both estrogen/progesterone peak in the middle of the luteal phase before returning to baseline.

This pattern of hormonal change between estrogen (estradiol) and progesterone is shown in the graphic below. Estradiol is the blue line, progesterone the black line. The top lines show changes in a woman’s body temperature with the increase occurring just after ovulation before dropping back to normal halfway through the luteal phase.

The Menstrual Cycle and Food Intake

The paper then examined research on energy (food) intake during different parts of the menstrual cycle. In animals, energy intake is reduced at ovulation (when estrogen peaks) and increases after ovulation when progesterone is peaking; this has long been interpreted as indicating that progesterone drove food intake.

Research in humans has generally borne out that pattern. Appetite tends to be the least right before ovulation, increasing as ovulation. Pointing out the often enormous variability between women, the increase in calorie intake during the luteal phase has been reported to be 90-500 calories per day.

The Role of Estrogen and Progesterone

It’s interesting to note that some research suggests that it is falling estrogen rather than increasing progesterone that drives hunger. Among its other roles, estrogen both improves leptin signaling in the brain along with sending a leptin-like signal to the brain. Falling estrogen would reduce overall signalling which would tend to facilitate hunger.

Of course, there is also some reason to think that it’s a combination effect of estrogen and progesterone that is having the overall effect. Given everything that’s changing at once, it is often difficult to determine exactly which hormone (or how they are interacting) is having a specific effect. This makes research on women incredibly difficult to do.

Tangentially, the paper mentions that estrogens might play an important role for weight and fat loss loss through inhibition of food intake. I’d also mention that a good bit of data suggests that estrogen is actually lipolytic, helping to mobilize fatty acids during aerobic activities. In fact, if you inject men with estrogen, they will mobilize fatty acids more effectively as well.

It’s actually even more complicated than this and estrogen can be seen to be having both positive and negative effects on fat loss (and regional fat loss). I discuss this in more detail in The Stubborn Fat Solution; sufficed to say that idea that ‘estrogen is bad’ in terms of fat loss is a simplistically incorrect one.

I bring this up for a couple of reasons. It’s interesting to note that with increasing fat loss, estrogen levels typically drop and this is probably part of why women’s hunger increases as they get leaner (there are tons of other adaptations occurring). Certainly falling estrogen doesn’t make women’s lower body fat any easier to get rid of.

The Role of Blood Glucose

Finally, the paper notes that some of the drive for appetite may be mediated by changes in blood glucose homeostasis. Empirically, some women seem to be more prone to hypoglycemia during certain phases of the menstrual cycle and falling blood sugar can stimulate hunger.

Ensuring that blood glucose levels stay stable might be extremely beneficial during those periods. For example, consuming moderate amounts of fruit during that part of the cycle (to ensure that there is always some liver glycogen to be released to maintain blood glucose) would be a useful strategy.

Cravings

The next part of the paper examines changes in macronutrient intake, food cravings and PMS. Studies, as usual, are inconsistent showing variously increases in carb, fat and protein intake during the luteal phase. Some of this may simply be related to being hungrier in general with no clear increase in desire for a specific nutrient.

Some research has indicated that the increase in carbohydrate intake is due to a specific craving although, with chocolate (a combination of carbs, fat and other micronutrients) being the most craved item, other possibilities exist. Cravings for a sugar/fat combo or something else entirely may be functioning here.

Alternately, the issue could simply be one of a magnesium deficiency. Some research indicates that magnesium supplements help with PMS related cravings and chocolate tends to be high in magnesium. Women may simply be self-medicating an important micronutrient. In this vein, many females report that their cravings are ameliorated if not eliminated when they are supplementing magnesium (e.g. 400 mg of magnesium citrate at bedtime, which can also help with sleep).

The Menstrual Cycle and Energy Expenditure

Next, the paper looks at the impact of menstrual cycle on energy expenditure (this brings us back to the increased body temperature I noted above). The major increase in energy expenditure occurs also during the luteal phase (when hunger is increased) with increases of 2.5-11.5% having been reported.

This only amounts to an increase of perhaps 90-280 calories per day and this has to be considered against the average food intake of 90-500 calories. While energy expenditure is up during the luteal phase, so is appetite; increases in energy intake can easily overwhelm the small increase in energy output if food intake isn’t controlled.

The increase in metabolic rate is thought to be primarily related to the increasing progesterone levels. So while increasing progesterone may not be driving the increased appetite per se, it may be stimulating metabolic rate slightly during the luteal phase.

The Impact of Birth Control on Body Weight

Next, the study examined the impact of birth control pills on body weight, first pointing out that there a number of different types of birth control containing synthetic estrogen, progesterone or possibly both. I mention this because, given the differences in each of the hormones (and their interactions), it becomes fairly inaccurate to talk about the “effects of birth control” in general terms.

Looking first at appetite, some studies have shown that birth control can increase total calorie and fat intake while others have no. With limited research available it’s hard to tell if this is due to differences in the types of birth control studies or simply individual variance between women.

As far as energy expenditure, while one study showed a small increase in basal metabolic rate of 5% with birth control intake (especially those containing a synthetic progestin), others have found no effect. Again, type of pill and individual variance is probably at play here.

Looking at body weight, most studies have apparently reported no substantial change in body weight with birth control pills although many show a trend towards increased body weight. One exception is Depo-Provera injections which are associated with the worst weight gain. There is also an enormous variation in response as I discuss in some detail in The Women’s Book Vol 1.

The Menstrual Cycle and Dieting

Finally the paper looks at potential implications for dieting and weight loss. The paper argues that considering which phase of the menstrual cycle the female in when starting a diet may be important. They argue that starting the diet premenstrually when hunger and food cravings are most intense may be a bad idea, just from an adherence standpoint.

Instead, starting a diet immediately following menstruation (or at a greater extreme 4-5 days prior to ovulation) makes far more sense since appetite will be most controlled. The paper does suggest increasing calories somewhat in the 5-8 days prior to menstruation to avoid a suboptimal calorie intake. I’m not sure I find this terribly practical for women who are dieting.

That said, the slight increase in energy expenditure during the luteal phase would allow a small increase in calories or the inclusion of a controlled amount of a craved food. Basically this is a time to consider implementing flexible dieting strategies.

The paper explicitly mentions that small amounts of dark chocolate should be allowed to improve dietary adherence (they argue that it is irreplaceable as a food due to cravings). Interestingly, I first read that idea in an older book called Why Women Need Chocolate which was an interesting look at the idea of biologically driven food cravings. I’d mention that one of the few studies to compare a diet based around the menstrual cycle (called Menstralean) applied this specific strategy with good results.

Additionally as I discuss in The Women’s Book, the luteal phase (or late luteal phase) is probably the best place to include a full diet break. Energy expenditure is up slightly and the increased food intake can help to avoid completely falling off the diet wagon. Scheduling it this way also allows the diet to resume in the follicular phase when appetite will be best controlled.

Of course, it’s also easy to look at that from the other direction; in theory at least, keeping calories controlled during periods when energy expenditure is up (for hormonal reasons) might generate superior fat loss. Of course, that also means keeping calories controlled when hunger is at its worst. Life, she is full of compromises.

Summarizing the Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Energy Balance

So that’s a look at some of the things that can occur (good and bad) in terms of food intake, energy expenditure during the menstrual cycle. It should be obvious that massive changes in hormones, including the interactions between estrogen and progesterone drive a great deal of processes that can impact on a woman’s food intake, energy expenditure and, of course, body weight.

I’d note again that the above processes tend to be exceedingly variable between women and while generalizations can be made from studies, women may need to track things like body temperature, weight and appetite through a couple of months to get an idea of how their bodies respond. Body temperature can be tracked as can things such as training capacity (some women find it very difficult to train effectively during certain periods of their cycle), appetite, etc.

In periods when hunger is off the map and/or blood glucose seems to keep crashing, increasing food intake slightly (and including moderate fruit) may be beneficial. For those women able to keep food intake under control during the part of the cycle when body temperature is up, increased fat loss may be possible.

Supplementing with various nutrients such as magnesium and fish oils seems to help with PMS symptoms and may help with food cravings during particularly difficult periods. Alternately, that may be a good time to include free meals or refeeds as discussed in A Guide to Flexible Dieting.

Rather than trying to fight the body’s tendencies (and losing control completely), finding ways to work with them may be better in terms of long-term results. Allowing controlled amounts of craved foods tends to help avoid problems with guilt and eating the whole box. Just keep it controlled.

I’d note, in concluding, that other more involved strategies have been suggested from time to time. Things like synchronizing the intake of carbs or fats with different parts of the cycle (e.g. eating relatively more carbs when carb metabolism is dominant and less when fat metabolism is dominant) have been suggested. I discuss this in even more detail specific to women in The Women’s Book.

Similar Posts:

- Female vs Male Physiology

- Why Isn’t There More Research on Women?

- Body Fat, EA or Hormones

- Does the EC Stack Stop Working?

- Meal Frequency and Energy Balance

I used to have the worst PMS symptoms – mood swings for sure. But out of control sugar and fat cravings. Surprisingly, the more fat I ate, the less sugar I craved during my PMS.

Next, I started a low(er) carbohydrate diet, keeping my daily carbs between 50-70 grams, pretty much every day. It’s been two months since I’ve been following this low carb and high fat (40% of calories to even 60% of calories) eating style, and also supplementing with fish oil and cod liver oil.

These two months….NO PMS. For the first time in my 27 year old life. And I’m not on birth control since 8 months….everything’s steady, normal….

A high fat (nuts, olive oil, eggs, meats) diet and a bunch of red meat has kept my PMS off…so no more falling off the eating/training cycle for 1 week ever 4 weeks.

Thought to share. Hope this helps folks out there!

Interesting… can’t wait to take advantage of those 5-8 days before menstruation to really burn some fat. However, I first need to get to the bottom of my amenorrhea so I can menstruate first! My MD’s basic blood test didn’t show any abnormalities so her conclusion was it’s “sport induced.” Her advice? stop being active and see if it comes back. Thanks, Doc! Also not a chance, as I’m probably around 17% bf (and trying to get contest lean for the first time.. not going so well).

I haven’t cycled in 6 months (since going off birth control pill). You have any research on this? Would love to see it if you do! Not so much research on the topic around — my trainer thinks there must be something greater going on since I’m not uber lean, while I’ve read in other places that simply having a low caloric intake and high energy expenditure can cause a woman with upwards of 25% bf to lose their cycle. And I’m stuck in the middle of it all with no period and stubborn fat!

(Just started reading your Stubborn Fat manual btw..so far, not really sure it applies to me yet — I’ve still got a nice layer of fat on my abs, tris, and thighs. Calipers estimate 15.6%)

Lyle,

In your own work with female clients, do you generally seek to link up training stress with the woman’s individual cycle, or do you take it on a case-by-case basis? e.g. you may link it up for some if needed but for others you don’t make any manipulations on account of cycle changes

For example, fluctuations in estrogen and its impact on ligaments (especially given ACL risk in female athletes) seems like one of those things to remain cognizant of, but at the same time I am wondering if it would be that major a concern in a well-trained female (or any female for that matter) engaging in a well-designed program focusing on progressive overload and quality of movement.

As always, thank you for the knowledge and your help.

Lyle, thanks for this great article.

As someone who has dealt with a hormonal imbalance since age 11, I can tell you that the impact of a menstrual cycle on fat loss and energy is HUGE!

I track my cycles very carefully and it has taken me 7 years to figure out what hormone pill works for me and what supplements I should take during different stages of my cycle. For years, I recorded everything from every mood swing, to temperature to food intake to quality of sleep and weight gain.

Unfortunately for me, I have endometriosis and PMDD, which if I let go untreated, it cripples me for days—and hormone/birth control pills is the only thing that helps. While being put on different pills, I found, as you mentioned, that some pills made me a bit crazy, some caused a significant gain weight and others made me feel like a one woman circus—all while trying to figure out what worked best with my raging hormones.

I found that exercising while I have a severe case of PMS really helps my mood/state of mind—my body might not feel like working out, (as I usually feel like a got run by a bus), but once I’m done, I feel 1000 times better. I also give me self a break if I’m having a particular hard day and let myself eat chocolate or ice-cream, if that’s what I’m craving (sometimes is weird/gross things I never eat like pickles and mayonnaise)—I do, however, keep it under control. Trying to time carbs during the time you are going to feel like eating everything in sight did not work for me. Once I started, it was just downhill from there. I think allowing yourself a small treat here and there is better than depriving yourself and then letting lose when your state of mind is a bit unstable.

I’m also much more aware of my body—in the sense that I know that those 3-5lbs hanging around my mid section right now will be gone in a day or two—not obsessing so much about the changes has helped me relax a little. It is hard sometimes when you wake up one morning and you’re suddenly a heffer! And you feel like all those days of watching what you put in your mouth and working your ass off at the gym didn’t pay off! That’s when you feel like ripping into a bag of Oreo cookies and have a threesome with Ben and Jerry!

My point is.. hormones are a bitch! And when it comes to fat loss, they are your worst enemy (or at least, it that’s what it seems)

Two anecdotal pieces: Always more successful starting a diet on day 1. There’s usually mild nausea and little desire for food, more energy for a workout, plus the fact that the bloating is leaving means a rapid loss – good for psyche. Basically side-steps that whole “I’m so hungry” first-day-diet issue.

Second, my cravings are for potato chips, which are the same sugar-fat combo despite the salt assumptions. Almost to the day 1 week ahead. Giving in is absolutely better than fighting it with things that aren’t satisfying (and giving in anway).

Finally – cocoa powder with splenda, hot water (or hot skim milk): has the nutrients without the calories.

Jack: It seems to be so individual. Some women seem to show massive variation in performance and such in training with distinct peaks and valleys in how they can train. For example, one trainee would have a dip right before ovulation when literally she couldn’t do anything in the weight room, right after menstruation she’d be ready to PR. So I would just schedule a light week/easy workouts for the bad week and a heavier for the next cycle with the other two weeks of the month varying similarly based on what we saw her being capable of (she usually had a second smaller dip in performance and a second smaller bump in performance). Others are much more consistent and don’t seem to have the issue. So I think approaching it on a case by case basis, keeping good records to see what’s going on. Certainly being aware of changes in hormones and how it affects connective tissues and such is a good idea to avoid injury.

Nicole: The data certainly suggests that it’s energy availability (roughly: intake – expenditure) that is the primary determinant of issues with hormone balance and loss of cycle more than body fat levels per se. Anne Loucks has done a lot of work on this. Body fat probably plays an additional and/or permissive role (inasmuch as it affects levels of hormones like leptin that are involved). There is also just massive variability, some women seem to lose their cycle more easily than others.

To everyone else: thanks for the comments!

Really interesting article! I’d love if you would also look into research about the different body physiology for menapausal women as it relates to weight loss and muscle gain. I don’t understand the hormal changes, but I do know that weight loss and muscle gain are harder than they used to be!

Really interesting article – I’ve been on a weight loss programme for nearly a year now and without fail almost all my biggest losses have been in the 4 or 5 days at the very end of my cycle. I’ve also noticed that if I go to the gym on the 1st day of my cycle I have loads more energy than at any other time (but that this can change quickly for the next 2 or 3 days).

I find the links fascinating – and would also like to learn more about what the links are between hormones and fluid retention.

This is a very interesting article. Its great to see it all in ‘black&white’. Personally speaking i cannot get enough food into me on day 1 and 2.. maybe what i need is rest but i have to keep going so i look to food for energy, but seriously i am like a bottomless pit. i do try to have ‘good’ foods around but chocolate has to factor sometime in those days.. without fail! other then that i thought i was always starving in the week or so before my period but realised that its actually day 22-24, then it seems to settle down a bit until day 1 and 2.. its different to normal hunger – it simply cannot be ignored! maybe its something to do with the fact that i’m a vegetarian.. who knows!

I’m trying to figure out why around the 4th day of my period and continuing on for another 5 days I have a definite increase in energy and a general feeling of well being.

How do I mimic this for the rest of the month?

I’ve heard a bit about how having too much soy can cause there to be too much estrogen in the body and therfore fat loss is halted… given this paper has just explained that estrogen is not the bad guy, could the ‘soy theory’ work in reverse? Is there any truth to the claims on soy and estrogen anyway?

I’m not sure what you’re asking in terms of ‘working in reverse’. There has been some work on anti-obesity effects of soy if that’s it. I’m not sure if the mechanisms have all been worked out but estrogen working through a central pathway might be part of it.

As to the phytoestrogen issue, certainly soy has bioactive phytoestrogens which, for the most part, tend to exert less of an estrogenic signal than estrogen in the body. Whether or not this amounts to any sort of biological effect depends entirely on teh amount consumed. In teh midst of the anti-soy hysteria, many lost the fact that actual daily soy intake in Asian cultures is fairly small, maybe 10 grams of protein per day. Which provide ~30 mg phytoestrogens. But Americans being Americans, people heard ‘soy is good’ and went nuts and started eating it in everything. And when you start mainlining soy, you do start to get biological effects. This is discussed in detail in The Protein Book.

Im not sure where to begin…I was diagnosed with PMDD several years ago. It truly is crippling. I have all of the emotional deregulation, depression,and anxiety. What is equally bad is the physical symptoms. Every month I can gain 8-10 lbs. I believe its a combination of water and over eating. My drive to train is dramaticaly decreases post ovulation. its interesting when I am training at the gym I find my self becoming angry at myself for being weak and angy at others for being near my space. I want to be annonomus everywhere but its impossoble giving what I do for a living. I will train, sleep, eat and see my patients. Ill often cancle therapy session with my clients because Im just too exhausted and honestly I dont care to be the emotional septic tank on those pms days.. Everyday ill spend a significant amount of time reseaching scholoarship in search of valadation. I will review the same literature multiple times from month to month for whatever reason it relieves my anxiety. Ofcourse this article was the jackpot…

When I start my pieriod…even a few days before I feel a since of calm, almost euphoric feeling. I am a different women. My clothes fit, I feel sexy, I cant wait to see my clients. I get an incredible amount accomplished in the next 18 days.

Thank you for doing this lit review. This paper was my xannax….

Hi Lyle

I have experienced major changes in my cycle (timing) and some extreme PMS. This has happened to me twice now. Once when i started dieting and training (over a year ago) and again these last few weeks (I was off of training and diet due to a major leg injury). Since being back on the diet and intense training my symptoms during ovulation are extreme. Major bloating and very sore breasts (i can’t even sleep on one side). This isn’t normal for me.

When my cycle went haywire last year i was on birth control pills and i dropped them hoping it would help and in a few weeks my cycle got back on track. There were also major PMS symptoms which were not normal for me but again they did subside.

Will starting an extreme calorie deficit and intense training change the way women react to those hormones, particularly progesterone?

Thanks

Dieting of all sort tends to impact on the menstrual cycle, lengthening one of the phases and shortening the other (and offhand I forget which is which). A researcher by the name of Ann Loucks has done a lot of work on this and found that the issue start with a ceratin threshold of energy availabiliity (roughly intake – expenditure) is crossed and that level is about 12 cal/lb. And it doesn’t matter if the deficit is from diet or exercise, the issues still arise (due to impaired LH release specifically).

Unfortunately, most won’t be able to lose fat without crossing that threshold. But if extreme deficits are causing you issues (and there is just HUGE variability between women in what responses occur), go with a more moderate deficit. The article Setting the Deficit – Small, Moderate or Large addresses this.

Lyle,

do you have any advice for women who have severely dieted , weight has remained the same (normal range) for long periods yet menstrual irregularities and other side effects visible? Bodyfat levels are in the 20’s yet. Do you suggest slowly raising calories to a higher level (coming from 800 or less). Would this aid in restoring normal menstruation/ovulation? Thanks!

Read the comment directly above yours, that addresses your question. And yes, you need to raise calories gradually.

Dear Lyle,

In the last couple of months I have experienced a changes in my menstrual cycle. In January my menstruation was late for 20 days. I had a stomach fly and I had vomited a lot and I lost a considerable amount of weight. I am 5’4 and 114 pounds. In the next months it stabilized. In May I travelled back home to see my family and I had a lot of stressful situations, I have to say that my father died last September and I am still in the grieving process. I am not a professional sport-woman but I tend to be physically active 4-5 times a week for 40 minutes. Running, swimming and playing tennis. I am also biking every day. I would like to know if considerable amount of emotional stress combined with physical activity and low calorie intake can delay my menstrual cycle?

I tend not to eat enough good fat. However I tend to eat more carbs, like pasta, roasted veggies and I eat a lot of fresh vegetable salads and fruits. I would like to know how I can improve my hormonal status and how I can make a balance of my hormones with food, exercise and rest?

Thank you!

This is such a great article. Thank you for your insight Lyle. I’ve been contemplating going on the pill to control moderate to severe PMS (specifically bloat/weight gain, hunger/cravings, & low mood), but don’t feel comfortable with taking hormonal pills. Not to mention it won’t aid in the cause for weight loss.

Lyle- I now understand the reason for hunger in terms of progesterone but what hormonal effects are happening as it relates to the mood? Is it the sudden increase in estrogen and even more increase in progesterone? If that’s the case, will going on the pill really help balance hormones throughout the cycle?

Thanks again! Amazing stuff!

I trained rigorously for a boxing tournament for a year. During that year pms progressively worsened. My symptoms were isolated to the 2 weeks before my period. There were days that I was soooo fatigued that had my boyfriend not picked me up out of bed and put me in the shower I probably wouldn’t have gotten up. I would sleep for at least 14 hours on days that my schedule allowed me to do so. My mood was all over the place and my stomach was a bottomless pit. After the tournament, which I won 🙂 , I took a year off to address my body. I am still no where near “normal” but have been able to identify that pms, particularly the fatigue, is something I have dealt with since the beginning of my menses. I just never linked the fatigue and my period because the symptoms would begin as much as 2 weeks before day 1. The symptoms just seem to have been extremely exaggerated by the intense training. I’m a bit intimidated by the idea of immersing myself in my training again with fear that it will all happen again. Thank you for this article though. I will definitely try the magnesium citrate.

I stumbled across this because I have been paying more attention during my luteal phase-I definitely have decreased stamina and as much as a 10 kilogram drop in some of my lifts. I’ve been playing around with my calories and am noticing some good results from adding about 100 calories every other day and remaining low CHO (around 50g with small fluctuations). My mentality is better, much less irritability, along with more endurance.

One night I tried a sort of refeed with about 700 extra calories and maybe 50-70 extra carbs-the next day I was leaner and my performance was amazing, but the following few days I was drained again. These more subtle fluctuations seem to be working better for me than the larger refeeds-this week I have been hitting PRs when normally I would feel weak. Oh and I seem to be losing belly fat when normally I begin feeling bloated-I’m thinking that too much caloric restriction could result in a stress response. Basically a controlled and small caloric increase might be healthier for those trying to avoid amenorrhea or binge disorders.