Even though I loved lifting weights since I was 15, I have probably been more involved in endurance sports than anything else over my varied athletic career. So I do get questions related to endurance activities and they do interest me. So today I want to look at the question: How do I carbohydrate load for endurance sports?

Specifically, I want to answer the following question:

What does the science say regarding the proper protocol for carbohydrate loading before a goal endurance event like a full marathon? As usual, internet articles are all over the place: some say 2 days, some a week or more, some say keep calories the same but higher carb percentage, some say to jack it up to 5-7 g/lb.

So there’s actually several questions to address here. Before getting to them, let me, as usual, start at the beginning.

What is Carbohydrate Loading?

The concept of carbohydrate loading is fairly simple. First and foremost it’s based on the fact that during fairly intense exercise, fat cannot contribute as much to energy production as most would like (folks spent decades trying to improve this but the fact is that near threshold intensities, carbohydrates are the primary fuel source).

At best fat adaptation increased the body’s ability to use fat for fuel at lower intensities, sparing muscle glycogen but it also came with some problems, including the impairment of the use of carbs for fuel (due to some enzymatic changes) during sprint performance. Since real sports have bursts and sprints (in contrast to studies which often use submaximal time to exhaustion), this is relevant.

In any case, the concept of carbohydrate loading is that through some types of dietary manipulations, the body’s normal glycogen stores (glycogen is carbohydrate stored in muscle and liver) can be overfilled, like overfilling the gas tank after the nozzle stops. This puts more fuel into the tank. So why is this useful?

Why Perform Carbohydrate Loading?

The basic reason for carbohydrate loading is that when glycogen (carbohydrate stored in the muscle) or blood glucose (produced from the liver) runs out, the athlete bonks. Their intensity drops enormously and performance craters. Fat can only fuel lower intensity activity and, once all of the carbohydrates in the body, the athlete can no longer sustain the high intensities required for performance or success.

Tangentially this is why endurance athletes involved in very long events (2 hours or more) consume carbs during either training or racing. The body’s carbohydrate stores are fairly limited and consuming carbs helps to limit the body’s need to use stored muscle glycogen up as quickly.

Who Needs to Perform Carbohydrate Loading?

A lot of people perform carbohydrate loading who really don’t need to. While you will occasionally see it stated that anything over 30 minutes can be limited by carbohydrates, this is really a blood glucose issue. It might be true if you went into the event from a low-carbohydrate depleted state but don’t do that. Generally speaking, it’s only when the event approaches 90-120 minutes of fairly high intensity (i.e. marathon pace is damn near threshold). At that duration and intensity, glycogen can become limiting.

Now the world record for the marathon is just over 2 hours but most take way longer than that and it’s actually slower marathoners that are probably more likely to get into problems. The elites might get away with consuming nothing during the event as they finish right before they run out of gas. But it’s close. For a 5k, an event that might take a recreational runner 30 minutes, carb loading won’t help and might hurt (since you tend to gain some water weight). Until you hit 60 minutes or more, don’t bother, just eat normally.

I’d mention that carb loading is often used by bodybuilders for various reasons. I used a carb-load phase in my Ultimate Diet 2.o and many use it for contest week to fill out muscles. Whether or not it does anything is debatable as hell with the one study I’m aware of showing no change in muscle size with the strategy (I can’t be asked to find the reference right now).

How to Perform Carbohydrate Loading

So back to the original question, how to carbohydrate load and why the difference in recommendations. Now a history lesson (I know how to party). Back in the 60’s or 70’s when carbohydrate loading was first thought up, and realizes that nobody knew nothin’ about nothin’, researchers sort of intuited the above and used the following protocol:

Glycogen depletion phase: 3-4 days of low-carbohydrate intakes with lots of training

Glycogen loading phase: ~3 days of a very high-carbohydrate intake as training was reduced

Which is basically the structure that I utilized in my own UD2. And it worked. Invariably muscle glycogen levels would increase by about 30% or so above normal levels, essentially given the athlete that much more glycogen to work with. Various parameters of performance improved as well.

The problem was that it wrecked the athletes. The low-carbohydrate phase coupled with lots of training was just brutal. It was also coming at a time when they really should have been tapering to begin with. It worked but it wasn’t workable.

So modified versions of carbohydrate loading would be developed and one of them at least was to more or less gradually increase carbohydrates over the final week of training while the taper was occurring. The effect wasn’t quite as pronounced from memory in terms of raising glycogen stores but it was a much easier protocol.

But there may be an even better way. Because it turns out that a single high-intensity workout followed by no more than 24 hours of carbohydrate loading can raise muscle glycogen to the same or higher levels than either of the above protocols. Specifically the researchers used a protocol of repeated 1 minute all-out interval training with 3 minutes of rest until the athletes couldn’t complete 30 seconds of cycling.

I applied this research to the relatively truncated (1.5 day) carbohydrate loading phase of my UD2 because I had to fit the cycle into a 7-day week. There I used whole body resistance training since I wanted to carb-load the entire body. Endurance athletes such as cyclists only need to glycogen load their legs.

How Much Should You Eat for Carbohydrate Loading?

Ok, the final part of the question above, should carbo-hydrate loading be a fixed amount or just keep calories the same and raise percentages? Short version, the first. Percentages are meaningless in the big scheme of things as 70% of 2000 calories isn’t 70% of 3000 calories even if both are 70%.

And I’ll explain why this is with another bit of trivia that I came across researching The Women’s Book. One of the earliest gender comparison studies had to do with the topic of carbohydrate loading. In it, male and female endurance athletes were trained and then carb-loaded with carbohydrates set at 75% of total calorie intake.

The researchers found that the women did not carbohydrate load while the men did. This led to the conclusion that there was a gender difference present and that women used fuel differently than men (which is true). But the conclusion wasn’t exactly right. Well it was right in that women didn’t carb load while men did. What was wrong was the reason for the difference.

Because when they looked at the data more closely, they realized that, due to women’s lower energy needs, they got less total carbohydrate in terms of g/kg or g/lb. Specifically, the women consumed 6-8 g/kg (about 2.7-3.6 g/lb) while the men got 7.7-9.6 g/kg (3.5-4.3 g/lb). That just points out the problem with percentages. Clearly 75% of 2000 calories is not the same as 75% of 3000 calories in terms of total intake. Due to being larger with a higher calorie expenditure, men get to eat more. And in this case it meant that their absolute carbohydrate intake was higher.

So the researchers repeated the study and gave both the women and men an identical total amount of carbohydrates, in the 7.7-9.5 g/kg range (3.5-4.3 g/lb). With this approach the women did carbohydrate load although still not to the same degree as the men. So there still appeared to be a systematic gender difference. But it still wasn’t exactly true.

Finally, the researchers gave both women and men 12 g/kg (5.7 g/lb) carbohydrate and found that they loaded equally. Basically the apparent gender difference wasn’t anything of the sort in terms of underlying physiology. It was simply an amount issue: when women eat the same absolute amount of carbohydrates as men they successfully load.

But this brought up a different problem, another that occurs a lot in female athletes. That problem was that the enormous amount of carbohydrates in the final study led to an impossible dietary intake. Specifically, carbohydrates now made up the entirety of their daily calorie intake which meant that there was no room for dietary protein or fat. In some cases, it required calorie intakes that were above the women’s maintenance levels.

This is an issue women run into quite a bit due to being smaller with lower energy expenditures. Their calorie intakes have to be relatively lower than in men and they often run into conflicts. This is especially true when it comes to fat loss where the lowered calorie intake may make it impossible to consume enough carbohydrates to sustain performance. Men, due to having more daily calories to work with, don’t run into this as much.

As I discussed at length in The Women’s Book, this points out why approaches that are perfectly appropriate for men may not be appropriate or even work for women. But I’m straying off topic.

Practical Carbohydrate Loading for Endurance Performance

The point of all of the above is that carbohydrate loading for endurance sports should be based on the total amount of carbohydrates consumed and not as a percentage of total calories. Maximum glycogen storage levels in the body are usually estimated at 12-16 g/kg (5.4-7.2 g/lb or a metric assload) but this includes upper body muscle mass which is usually of less relevance to most endurance sports.

For a 70 kg (154 lb) athlete that would be an intake of 840-1120 grams of carbohydrates or between about 3200 and 4400 calories worth. Like I said, a metric assload of carbohydrate.

For carbohydrate loading just the lower body muscles, 10-12 g/kg (4.5-5.4 g/lb) of total carbohydrate is generally sufficient.

For a 70 kg (154 lb) athlete, that comes out to 700-840 grams of carbohydrates or 2800-3200 calories or so.

Whether or not this is done over several 2 days, 2 days after depleting glycogen or 1 day after a short high intensity workout seems to not matter so long as the total amount is consumed.

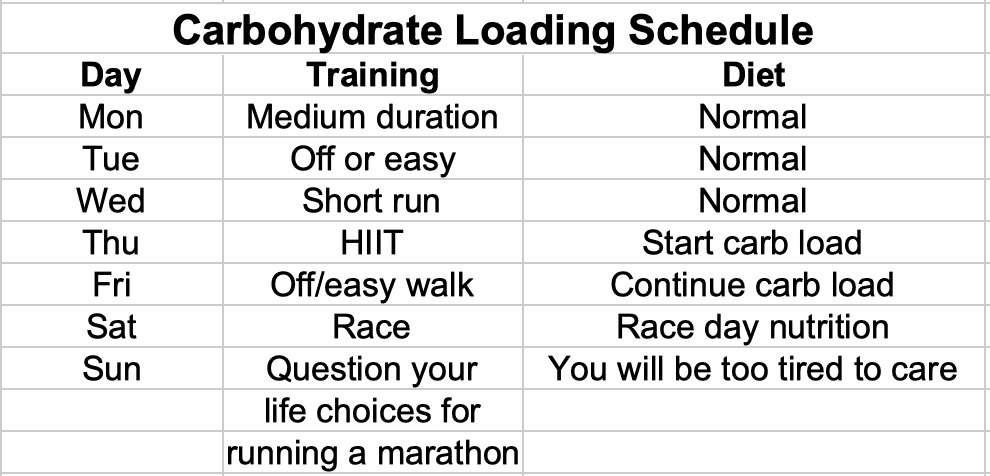

Assuming that amount of carbohydrate can be eaten in a day, I think using the one day high-intensity workout protocol is easiest. I’ve provided a sample schedule below assuming a Saturday morning marathon.

The schedule should be fairly explanatory. Most marathon runners do their long run on Saturday and often their last truly long run two weeks before the race. During the week, you’re simply tapering your training down to allow for recovery. On Thursday do a short interval workout to prime the body for the carb-load. Start on Thursday after that workout. On Friday, take it off or an easy walk while you continue carb-loading. You should be rested and ready to go on Saturday so that you can be completely destroyed on Sunday.

Race Day Nutrition

So far as race day nutrition, I can’t cover everything. In general, a small carb-based meal would be eaten several hours up to an hour before the event although runners must be careful not to have food jostling around in their stomach. Generally recommendations are 1-4 g/kg carbs 1-4 hours before the event. The earlier the meal the more carbs you should eat. A small amount of protein and minimal fat and fiber are best here, you don’t want food digesting when you start running. Have some fluids with this so you’re fully hydrated.

Note: you should always always always test any pre-run meal in training. Never ever try something new on the day of the event that you haven’t experimented with or you will have a bad time.

During the race you will need to drink water and some type of carbostuff. Running is much harder in this regard than cycling. You don’t usually carry a water bottle and are limited to water and feed stations. Many runner use carbo gel or Gu or whatever but you still have to drink fluid.

However, don’t go nuts with the fluid intake. Slower marathoners often overdo the water (often gaining weight over the course of the race). This can throw off their electrolyte imbalance and, at the extremes cause, hyponatremia. Some people have died. Faster runners don’t run into this problem since they don’t have to drink as much to finish and generally can’t due to their running speed.

Facebook Comments