For decades now, ever since people started talking about cholesterol and heart disease, there has been a combination of concern and confusion over the topic of dietary fats. So let me see if I can unconfuse things. First, let me start with some basic definitions.

Table of Contents

Triglycerides, Cholesterol, &c

While people tend to throw around the term dietary fat somewhat loosely, the fact is that not all of the dietary fat that we consume on a daily basis is the same. Here I’m not talking about saturated versus unsaturated fats. Rather, I’m referring to the different distinct chemical types of lipids (just another word for fats).

The primary two that folks eat on a day to day basis are triglycerides (TGs) and dietary cholesterol. Dietary triglyceride contributes the bulk (over 90% of the total) of the dietary fat that we consume on a day to day basis.

We also consume small amounts of other lipids in the diet such as phospholipids. Since they make up such a tiny proportion of our daily fat intake, I won’t discuss them. Instead, I’ll focus only on TGs and cholesterol.

TG and Cholesterol: What’s the Difference?

It’s fairly common for people to be a bit confused about triglycerides and cholesterol, either confusing them with one another or considering them identical. This most likely stems from the extreme focus on cholesterol levels and heart disease that really picked up in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Since many foods high in cholesterol are also high in fat, this confusion is understandable. But this is far from universal. Cholesterol is only found in foods of animal origin, it’s part of the cell wall structure. And there is no doubt that high-fat animal based foods are also high in cholesterol. But that doesn’t make high-fat and high-cholesterol synonymous.

However, a food can be high in cholesterol but low in fat (i.e. shellfish) or

high in fat and have zero cholesterol (i.e. full fat cheese).

More importantly than that dietary TG and cholesterol are completely different structurally, chemically and in how they impact the body physiologically.

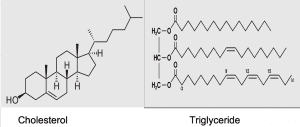

Cholesterol is what is termed a steroid molecule. It has a complex ring like structure and one of it’s main functions in the body is as a precursor molecule for other compounds with a similar structure (such as testosterone, cortisol, estrogen, progesterone and others). As mentioned above it’s also part of cell wall structure.

In contrast, the dietary fats that make up the majority of our daily intake are more accurately called triglycerides (or tri-acyl-glycerols if you want to be fancy). They have a chemical structure where three fatty acid chains (‘tri’ = three) are bound to a molecule of glycerol (which is where the ‘glyceride’ part of the name comes from).

You can see the chemical structure of both dietary cholesterol (left hand picture) and a triglyceride molecule (right hand picture) below.

Clearly they are completely different in their structure.

I should mention that there are also dietary diglycerides (two fatty acids bound to a glycerol molecule) which are occasionally found in dietary supplements. They may have slight fat loss benefits and increase fullness. There has also been some interest in dietary monoglycerides, single fatty acids, for appetite control. But outside of specialty products, the majority of dietary fat we consume will be triglycerides.

Of Dietary Cholesterol and Blood Cholesterol

Let me continue by looking at the issue of dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol. I’m not going to get into the debate over the role of blood cholesterol and heart disease. Sufficed to say I find both extremists arguments are all misguided.

Certainly the idea that blood cholesterol was THE cause of heart disease is incorrect. But the overreaction that it plays NO role in heart disease is equally incorrect. Heart disease is multi-factorial and issues of total blood cholesterol, HDL/LDL ratios, small and large particles, blood triglycerides, inflammation and many others play a role.

Even when I was in college at UCLA in 1993 it was well known that cholesterol had to oxidize before it could form plaques in arteries. That has more to do with oxidant stress and anti-oxidant intake than anything else.

In any case, what is often forgotten is that the body usually makes more cholesterol in the liver than people eat in a day. As well, the body tends to adapt cholesterol production in the liver to intake. If you eat less dietary cholesterol, the body will make more. If you eat more, the body will make less.

Which is part of why the entire focus on dietary cholesterol was misplaced to begin with. Only a small portion of people show an increase in blood cholesterol due to their dietary intake. For most it’s a non issue and worrying about cholesterol intake per se is pointless.

And as it turns out, the primary controller of cholesterol metabolism in the liver turns out to be dietary fats themselves. This at least partially explains the connection between the two but requires a discussion of the different types of dietary fats.

Types of Dietary Fats

From this point forward I will be using the term dietary fat to refer only to triglyceride molecules, just for simplicity. Typically dietary fats are divided into four broad categories which I’ve listed below.

- Trans-Fats

- Monounsaturated Fats

- Saturated Fats

- Polyunsaturated Fats

Note: There are also divisions basead on chain length and you will hear about short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), medium chain fatty acids (or MCTs, medium chain triglycerides), and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA). SCFA are actually produced in the body from the fermentation of fibers. MCT is found in some foods but is usually used as a dietary supplement. Mostly we consume LCFA in the diet.

You’ve probably heard or read these terms before but what do they mean? In a chemical sense, they refer to the actual chemical structure of the fat. More specifically it refers to the chemical structure of the individual fatty acids.

It has to do with the shape of the molecule and whether there are single or double bonds. Saturated fats have no double bonds, the carbons are saturated. Monounsaturated fats have one double bond (“mono” = one) and polyunsaturated fats have more than one double bond (“poly”= many). Trans fatty acids are flipped chemically from Cis-fatty acids. It’s an organic chemistry thing and I don’t want to get any more into the weeds on this.

Strictly speaking any given TG could have three different types of fatty acids on it. So conceivably one might have one saturated, one monounsaturated and one polyunsaturated fatty acid. But nobody really thinks in those terms and I think it would be rare for this to occur.

Rather, fats tend to be predominantly one type of fatty acid or the other. And certainly we don’t talk about fats in terms of their individual fatty acids. We just call them a saturated fat or what have you. I don’t honestly know the naming convention on this, I suspect that if 2 out of the 3 are the same that determines the overall type of fat.

So now let me look at each of the 4 types of fats. I’ll focus on what they are, where they are found in the diet, their health effects, etc.

Trans Fats

Of all the dietary fats, trans fats/trans fatty acids (aka partially hydrogenated vegetable oils) have the least amount of debate or controversy over them. Certainly they have gotten the most bad press in recent years. So let me get them out of the way first.

Trans fatty acids are a semi-solid fat which are made by bubbling hydrogen through vegetable oil. This causes that vegetable oil to become partially hydrogenated, hence the name. The purpose of this is to make vegetable oils, which go rancid easily, more shelf-stable. This is important when foods will sit on a shelf for long periods.

While trans fatty acids are found in many commercial foods, perhaps the most well known is margarine, a semi-solid butter substitute.

While trans fatty acids are often thought to be completely man-made this isn’t entirely true. There are naturally occurring trans fats which are found in small amounts in foods. But quantitatively, most of the trans-fats people eat will be from processed foods.

The problem here is that the process of partial hydrogenation changes the chemical structure of the vegetable oil. As I mentioned above, the normal cis-configuration of the fat is flipped to a trans-fat. And the human body isn’t equipped to handle these chemically altered dietary fats.

For that reason, intake of a large amount of trans-fatty acids causes a number of problems in the body.

As a 2009 review on trans-fatty acids states:

TFA [trans-fatty acid] consumption causes metabolic dysfunction: it adversely affects circulating lipid levels, triggers systemic inflammation, induces endothelial dysfunction, and, according to some studies, increases visceral adiposity, body weight, and insulin resistance…Consistent with these adverse physiological effects, consumption of even small amounts of TFAs (2% of total energy intake) is consistently associated with a markedly increased incidence of coronary heart disease.

I am rarely a a fan of nutritional absolutes as context is always key. However this is a rare occasion when one is warranted and there is literally no debate.

Trans-fatty acids have no place in human nutrition.

There is simply no disagreement on this topic that I have ever seen. Their daily intake should ideally be zero.

Monounsaturated Fats

Let me move next to monounsaturated fats, another fat about which there is little controversy nutritionally. Monounsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature although they may be found in solid form in foods.

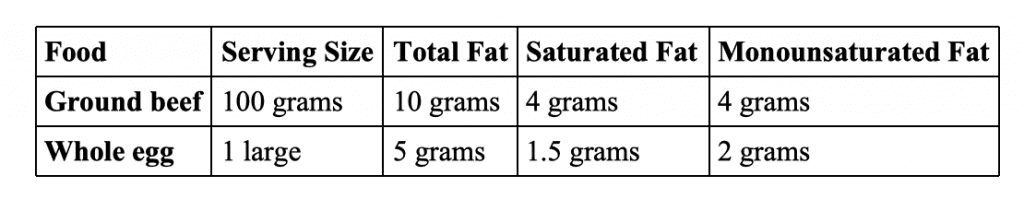

The primary monounsaturated fat is oleic acid which is found in olives and olive oil. Hence the name. I’d mention that oleic acid is actually the primary fat found in most high-fat foods to begin with. This includes those that most think of as containing large amounts of saturated fat. You can check this at USDA database and I’ve shown two examples below.

In terms of its health effects, there is little controversy over monounsaturated fat. At worse they are fairly neutral from a health perspective. This is especially true in terms of their effects on blood cholesterol levels. But there is also good evidence that oleic acid has health benefits.

It’s thought that part of the benefit of various Mediterranean diets is related to the large intake of olive oil in the diet. I’d mention that there are clearly other parts of the diet that contribute to its health benefits including a large intake of fresh vegetables and others.

It’s also worth considering that some of the health benefit seen when people increase their monounsaturated fat intake is as related to reducing the intake of other “unhealthy” fats. Regardless, there’s no debate that monounsaturated fats are healthy.

Given how prevalent it is in the food supply, oleic acid will make up a large proportion of someone’s fat intake almost without trying. An exception might be someone eating a LOT of processed high-fat foods.

When people are looking to “add fat” to their diet, it would be difficult to go wrong using oleic acid/olive oil as a source. It can be added to salads and there are brave souls who put it directly into protein drinks. For people who don’t like the taste of straight olive oil or olives, there are high oleic safflower oils.

Saturated Fats

Ok, saturated fats. For decades now, saturated fat has been the whipping boy of the nutritional world. It was only recently that trans-fatty acids took over the number one spot for most hated dietary fat.

Saturated fats are solid at room temperature (think the fat on a steak) and are found almost exclusively in animal products. There are a couple of exceptions. Both coconut and palm kernel oil contain a lot of saturated fat but much of this is in the form of the MCT’s I mentioned above. While liquid, milk fat contains saturated fat.

Saturated fats seem to have been blamed for everything wrong in the world including heart disease, diabetes, the downturn in the economy and the dissolution of the nuclear family. I’m only slightly exaggerating here.

At the same time there has been a niche countermovement arguing that saturated fats are not only NOT unhealthy but objectively healthier. Some even argue that they are healthier than the polyunsaturated fats discussed next.

It’s easy to see how people are confused.

Anybody who reads my site or knows me knows that I dislike nutritional extremism. Extremist stances are invariably wrong and frequently one is nothing more than an over-reaction to the other. The truth, almost always, lies in the middle.

And while I know many will disagree, this holds true for saturated fats. For anybody who reads nutritional research there is no debate that it causes various problems in the body. It tends to increase blood cholesterol levels (by impacting liver metabolism), causes inflammation and is stored more easily as fat than other fats.

There is simply no debate about this unless you want to stick your head in the sand and call every piece of data on the topic “shill science”. Which hilariously is that the pro-saturated fat extremists usually do.

But it’s also more complicated than this.

Saturated Fats and Health

Part of the problem here is that saturated fats are a class of dietary fats. By that I mean there is no singular saturated fat. Lauric acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid and many others are all saturated fats based on their chemical structure.

But that doesn’t mean that they act identically in the body. Some specific saturated fats have negative effects, others are neutral and some are positive. For anyone interested in some of details of this, I recommend an older paper called Saturated Fats: What Dietary Intake.

To that I’d add the following: you can’t ever isolate the impact of a single nutrient outside of the rest of the diet. This is the problem inherent to conclusions coming from epidemiological research. But epidemiology is crap.

For someone who is lean and active, who eats plenty of fruits in vegetables and who is in calorie balance, there may be no effect of saturated fat intake. I recall an older study in cyclists which found exactly that. So long as they were in calorie balance, increasing saturated fats had no negative effects. Presumably they just burned them off.

But that doesn’t describe everyone. And certainly not the average individual for whom dietary recommendations are usually written. Someone who is overweight (which is in itself inflammatory), inactive, under a lot of stress, not eating fruits/vegetables, etc. saturated fat intake may be extremely damaging.

Recall above that it appears to be oxidized cholesterol that forms plaques. An athlete with a solid anti-oxidant intake and system is at less risk of this than someone who is not. Context is always key.

I’d note that weight loss and weight gain drastically impact on blood cholesterol levels and health risk. In almost all cases, regardless of diet, if weight or fat is lost, blood cholesterol goes down. If weight or fat is gained, it goes up.

I’d also mention that the changes in blood cholesterol with saturated fat intake tend to occur in both the “good” and “bad” cholesterol fractions. We’ve known for decades that total cholesterol is only part of the story. If decreasing saturated fats reduces both good and bad cholesterol, the overall impact on health risk is more complex than it might first seem.

My point being that I find both extreme camps to be extremely silly. Not all saturated fats are the same, their intake must be considered in context, and thinking of them as good or bad is missing the point.

From a body fat perspective, it’s at least worth mentioning that saturated fats tend to be stored a bit more easily than polyunsaturated fats. They are also a bit more difficult to mobilize once they are stored within fat cells. I discuss this in detail in The Stubborn Fat Solution.

Polyunsaturated Fats

Finally there are the polyunsaturated fats. Unless they are found in foods, these types of fats are always liquid at room temperature. Like saturated fats, polyunsaturated fats refers to a category or class of fats.

That is, there are multiple types linked only by the fact that they have more than one double bond in them. It is the presence of this double bond that makes them unstable in foods. Hence the development of partial hydrogenation.

Of the polyunsaturated fats, the two I want to focus on are the omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. You’ll see these referred to as w-3/n-3/ω-3 or w-6/n-6/ω-6. The naming just refers to the structure of the individual fatty acid and you don’t need to know more beyond that.

The primary w-3 fatty acid is alpha-linolenic acid, abbreviated ALA (not to be confused with alpha lipoic acid). The primary w-6 fatty acid is linoleic acid, abbreviated LA.

I always have trouble remembering this but here’s my trick: 3 is smaller than 6 but alpha-linolenic acid is longer than linoleic acid. So the smaller number goes with the longer name.

Among other things ALA and LA have the distinction of being the two essential fatty acids (EFAs). By that I mean that they can’t be made in the body. Rather, it is essential that they be present in the diet. I’ll come back to this below as there is some debate over ALA and LA being essential per se. Rather, fats that they are converted to may be the truly essential nutrients.

This is actually in contrast to all of the other dietary fats I’ve described. If you never ate another molecule of trans-, monounsaturated or saturated fats you would suffer no health consequences. But a long-term deficiency of the EFAs would eventually cause a host of health problems.

As a bit of trivia, it actually took years for nutritional research to establish if ALA and LA were truly essential. It was only through the most artificial of diets, a literally ZERO fat hospital diet that they generated a deficiency. Basically even the worst fat containing diet will tend to cover minimal requirements for the EFAs. But minimum should not be confused with optimal.

Polyunsaturated vs. Saturated Fats

When saturated fats started to become “the enemy” in the 70’s and 80’s, there was a big push for an increased intake of vegetable oils in the diet. Basically, if people were going to eat a lot of fat, vegetable oils would be superior to saturated fats.

But things were not quite that simple. The same pro-saturated fat groups believe that increased vegetable oil intake was the cause of the health problems typically blamed on saturated fats. Mostly they focus on the polyunsaturated fats and there is at least a tiny bit of truth to their arguments.

Now I’ve confused everybody. So let me unconfuse things.

The Effects of ALA and LA

While many thing of fats as nothing but calories to be stored, this is untrue. Fats act not only a source of energy but as signalling molecules and precursors for other compounds such as prostaglandins that have far-reaching effects in the body.

This is true of all fats but especially for ALA and LA. Through various mechanisms they modulate inflammation, modulate gene expression, act as precursors for eicosanoids, along with many others.

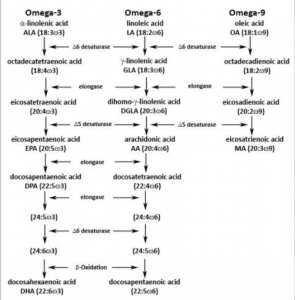

Importantly, many if not most of those effects are mediated by compounds formed by the metabolism of ALA and LA within the body. That is, ALA and LA can be seen as “parent” compounds for other chemicals in the body.

For example, LA is converted to gamma-linoleic acid which may have anti-inflammatory effects. Many women swear it helps with their PMS symptoms. LA is also converted to arachidonic acid (not related to spiders) which is an inflammatory compound. It may also be involved in muscle growth.

ALA undergoes extensive metabolism an is eventually converted to EPA and DHA. I’ll spare you the names but these are more commonly referred to as the fish oils, due to being found in high amounts in fatty fish. I’ll come back to this below.

The metabolism of both ALA and LA is shown below (w-9 fatty acids are also shown)

Of more importance, the effects in the body of ALA and LA are often not only different but frequently oppose one another. To put it very simplistically, the w-3 fatty acids tend to have “good” effects while the w-6 have “bad” effects.

The W-6 to W-3 Ratio

The difference in overall effects of the w-6 and w-3 fatty acids is potentially an issue due to the overall ratio of both in the modern diet. It’s thought that our evolutionary diet had a ratio of 1:1 to 4:1 of w-6:w-3. In contrast, the modern diet has a ratio of 20-25:1.

This skewed ratio is due to two factors. The first is the overabundance of w-6 in the food supply, especially in commercial vegetable oils which are usually high in w-6 and low in w-3 (flax and hemp oil being two notable exceptions).

The second is the relative lack of w-3 fatty acids in the modern diet. The most common source of w-3 fatty acids is in cold water fish (hence “fish oils”). Outside of cultures that consume those regularly, their intake is low. There has been great interest in boosting the w-3 content of foods (i.e. high w-3 eggs) for this reason.

And it’s been argued that this skewed w-6:w-3 ratio is contributing to health problems including inflammation and increased heart disease. But research calls this into question.

In the paper Too much linoleic acid promotes inflammation, doesn’t it? Kevin Fritsche writes:

Existing evidence in humans, though limited, fails to show a link between higher dietary LA intake, or higher plasma LA, and greater inflammation in vivo. In fact, some of the data suggest the opposite may be true [my note: he’s saying that increased LA intake may be ant-inflammatory].

In a paper titled The Role of Dietary N-6 Fatty Acids in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, Walter Willett write:

Because n-6 fatty acids are the precursors of proinflammatory eicosanoids, higher intakes have been suggested to be detrimental, and the ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids has been suggested by some to be particularly important.

However, this hypothesis is based on minimal evidence, and in humans higher intakes of n-6 fatty acids have not been associated with elevated levels of inflammatory markers…

In the United States, for example, intake of n-6 fatty acids doubled and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality fell by 50% over a period of several decades. In a series of relatively small, older randomized trials, in which intakes of polyunsaturated fat were increased (even up to 20% of calories), rates of CHD were generally reduced.

So some of this concern may be misplaced but I’m not getting into the debate much further than that.

I will only note that obtaining sufficient w-6 in the diet is trivial. With even the most moderate fat intakes, w-6 intake will be more than sufficient. Whether or not intake need to be reduced is a different issue.

Perhaps the bigger issue here is not that w-6 intake is excessive but that w-3 intake is utterly insufficient.

The W-3 Fatty Acids

As I said above, the bigger issue with the modern diet may be less the high w-6 intake and more the low w-3 intake. Now, recall from above that both w-3 and w-6 fatty acids undergo significant processing in the body.

Specific to this section, the parent w-3 ALA is converted to EPA and DHA (at least potentially, I’ll come back to this). It’s EPA and DHA I want to talk about now. As I mentioned above, EPA and DHA tend to be called the fish oils due to being found in high amount in fatty/cold-water fish).

Quite in fact that original interest in these dietary fats came out of studies on cultures such as the Alaskan Inuit. Despite high fat intakes, they showed low rates of heart disease. Among other reasons, their high fish oil intake appeared to be part of it.

And now decades later, about a zillion (+- a million) studies have found benefits of increasing w-3 intake. They reduce inflammation, improve blood lipid levels (decreasing blood TG levels), decrease the risk of heart disease, may help with depression or slightly increase fat loss.

Actually, let me qualify that. It’s not uncommon to see articles or research papers concluding that w-3 have none of the above effects. These are frequently published in scientific journals with a known anti-supplement bias. Invariably the issue is one of dose. When sufficient fish oil supplements are given there are benefits. When they aren’t, there aren’t.

I mentioned above that there is some debate as to what the actual “essential” fatty acids are. That is, are ALA/LA essential themselves or is it the EPA/DHA and other compound that they produce that are.

It certainly looks like, in the case of the w-3’s, it is the EPA/DHA that are truly essential. Whether ALA does anything independently of it’s conversion to those compounds is currently being debated.

Some might argue whether or not this matters but in this case it does. Because technically the diet can be supplemented with ALA (i.e. hemp or flax oil) or directly with pre-formed fish oils (there are also vegan friendly EPA/DHA supplements). And which is superior depends on the efficiency, or lack thereof, of the conversion of ALA to EPA/DHA.

W-3 Conversion in the Body

Because it turns out that the conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA is not fantastic in most adults. When ALA is supplemented the actual conversion to EPA is only about 4-5% and the conversion of EPA to DHA is almost zero. Even supplementing with EPA won’t raise DHA in most people.

Note: Vegetarians and vegans show a higher rate of conversion of ALA to EPA/DHA, I don’t know why. Also, women are better than men at converting EPA to DHA. This is likely due to the importance of DHA for the developing fetal brain.

Which means that just ensuring sufficient intake of ALA does not ensure that EPA and DHA levels in the body will go up sufficiently. Quite in fact, it’s clear that they won’t.

There are two consequences of this.

- Unless ALA has its own independent health effects, I don’t think it can be the essential fat. EPA and DHA are clearly the big drivers on this.

- Unless someone is willing to increase their fatty fish intake, the only way to ensure sufficient EPA/DHA intake is with preformed fish oils.

Various forms of supplements are available including fish oil capsules and liquids such as Carlson’s oil. The latter can be used as salad dressing or put into a protein drink. I’m sure some drink it straight.

I mentioned above that there are w-3 fortified foods becoming available. But overall I don’t find them cost effective. The amount of w-3 is very small and they usually cost about three times as much as the normal food. It’s cheaper to buy regular eggs and fish oil pills than high w-3 eggs.

So far as dosing, I’ll only note with some glee that my recommendation from over 15 years ago of 1.8-3.0 grams of preformed EPA/DHA per day seems to be about the effective dose for health effects. Studies using less than this invariably find little to no effect. Man it’s good to be right.

Fragile Fish Oils

Let me note that w-3 fish oils are very fragile. By this I mean that they can be oxidized or go rancid with exposure to light, heat or air. Another part of the anti-polyunsaturated fat cult has to do with this.

They argue that the high potential for polyunsaturated fats to oxidize makes them unhealthy. This might be contextually true if a LARGE amount of those fats are consumed. Or if anti-oxidant intake isn’t sufficient.

At least some fish oil supplements include Vitamin E to help limit oxidation. Keeping fish oils supplements cold, in a dark closed bottle avoids most of this too.

Basically they are taking the situation of an extreme intake and throwing out the baby with the bathwater and excluding the middle. Would I ever argue that eating more and more polyunsaturated fats is better? No.

But the only option aren’t none and too much. Optimal intakes are always the goal.

Dietary Fat Recommendations

I should probably give some general dietary fat guidelines. In most cases, a dietary fat intake of 20-40% or so is probably about ideal. Yes, there are exceptions.

On average I’d recommend a starting fat intake at 0.25-0.5 g/lb (0.5-1.0 g/kg). For a 180 lb male that’s 45-90 grams of fat. For a 130 lb female that’s 33-65 grams of fat per day.

Most ‘high-fat’ foods contain a mixture of saturated and monounsaturated fats to begin with and this usually works itself out on its own. It’s nearly unheard of for anybody to get insufficient w-6 intake unless their dietary fat intake is near zero for long periods of time. Even here there is a year’s worth of w-6 stored in your fat cells. Deficiencies are unheard of.

The singular most important factor is to get sufficient amounts of EPA/DHA. Flax and hemp oil are not ideal due to poor conversion. A smaller female might aim for 1.8 g/day of total EPA/DHA. A typical fish oil capsule might contain 300 mg of EPA/DHA total so that’s 6 pills per day (6 total grams of fat). There are high concentrate pills as well. A larger male might target 3.0 g/day. 10 pills per day of regular concentration.

Summing Up Dietary Fats

So what started out as a short primer got a little bit out of hand. At this point you should understand the difference between dietary fats and cholesterol in terms of their structure in the body.

Hopefully I’ve helped to clear up at least some of the confusion regarding different types of dietary fats. Trans fats, for all purposes, have no place in the diet. There is almost no debate that monounsaturated fats are either de-facto healthy or at least health neutral.

There is slightly more debate over saturated fats but this is mainly due to niche extremists overreacting to the anti-saturated fat hysteria. Some saturated fats are good, some are neutral, some are bad. Their intake must be considered within the overall context.

Polyunsaturated fats are generally regarded as good although the same niche groups tend to decry them. There may be some potential issue with w-6:w-3 ratios. Ensuring w-3 intake is sufficient is arguably the most important part of this. Since the body is terrible at converting ALA to EPA/DHA, most will need a preformed supplement to obtain optimal amounts.

Similar Posts:

- The Mercury Content of Fish

- A Guide to Basic Nutrition

- Dietary Protein Sources – Other Factors

- Controversies Over Carbohydrate and Fats

- Examining Some Dietary Protein Controversies

Mr. McDonald, first off just wanted to add that i respect your work and always look forward to your posts. I have an honest question that I ‘m hoping you might have an incite to. One of my clients is a female that has been quite overweight since her youth. She’s not one of those who just let herself go and put on pounds. Her parents are actually quite thin yet her and her sisters are all overweight. She came to me at 340 and is currently at 295. The problem for us and the question that I have for you is that she is making a good 3-5 lbs. loss every other week and the week in between, she either stays put or even gains a pound! I change her workouts about every two weeks and I change her calories intake every so often as well. She follows a high protein, mod fat, and low carb diet which seems to be working somewhat but these weeks of zero progress are killing us. Do you have any ideas?

Lyle,

On the topic of fats, I’ve noticed that the folks from Parrillo seem to treat them as something of a bogeyman and often recommend fairly low intakes to prevent fat gain. Do you have any theories on what would precipitate such a view? It seems to fall into one of those “extreme” viewpoints, but I’d be interested in your quick thoughts on the matter.

I look forward to part II.

Thanks.

~Jack

Great article! i was just wondering what your thoughts are on the “Anabolic” style bodybuilding diet. I have been following the guidelines of this style of eating and have gains 10 lbs of muscle mass in only 5 weeks! The results for me have been amazing. Do you think that there is a problem with consuming high amounts of dietary fat and dietary cholesterol on a daily basis? Just wondering what your thoughts are.

I liked your quick treatment of the cholesterol controversy (try saying that five times fast). For people who are left wondering, there is a marginalized minority (try saying THAT five times fast) of scientists/physicians who believe serum levels of the various forms of cholesterol correlate with heart disease but are not causally involved in cardiovascular pathology. They gave some interesting ideas and theories but IMHO their credibility and objectivity is seriously impoverished by the nuts in their group that throw in the whole AMA/AHA conspiracy theories that entail this grand subversive political machine that maintains this facade due to the the profitability of treating heart disease with statins and a host of things. These are the people who rightfully belong on the fringes of academia and the clinical community who will also tell you that HIV doesn’t cause AIDS and that America has a cure for cancer but makes too much money treating the disease to release it or whatever. Yes, that makes perfect sense; it’s not that the etiological underpinnings of cancer and resultant metastasis is dictated by a set of distinct and independent physiological processes that are so complex and diverse that finding a universal cure is an exceedingly difficult and arduous task despite our best efforts. No, it’s because we don’t want to cure cancer because it keeps the population down and/or we make much more money treating it vs. curing it. I’m sure that’s it.

I really shouldn’t lump all the cholesterol dissenters into this group; many of them are rational and truly believe their lines of evidence contribute enough reasonable doubt to question the causality of blood cholesterol and heart disease, I’m just not on board with them. When the data came out that showed statin use reduced all cause cardiovascular mortality that pretty much sealed the deal for me. i dunno, it’s interesting.

Abel: Water weight does goofy things to weight loss. That’s all it is. Weight loss is rarely consistent week in week out and women moreso than men are prone to weirdness with water balance. The article i posted last week on Whooshes and Squishy Fat talks a little bit about it. As long as she’s losing that much consistently, don’t worry about it.

Jack: Parillo has long been a believer in VERY low fat diets but usually supplemented with enormous amount of MCT’s. I imagine a lot of his ideas come from the old literature suggesting that overfeeding with fat led to more fat gains than overfeeding with carbs. That’s my best guess though.

Nick: What literature exsists on the issue of blood lipids and full blown ketogenic diets (The Anabolic Diet is a cyclical ketogenic diet) suggests that as long as fat is being lost, blood lipid levels typically improve. But if it is gained or maintains, things often get much worse. I discuss what research exists in my book The Ketogenic Diet

Chris: Yeah, what you said. As I noted, I find the extremists in both camps to be a bit myopic. Clearly blood cholesterol isn’t the ONLY issue at stake for heart disease risk. Triglycerides, homocysteine, anti-oxidant levels (early research suggesting that it was only oxidized blood cholesterol that caused plaque build up) all play a role. But going from “It’s not the ONLY cause” to “It’s not a risk factor at all” is just jumping from one dumb extreme to the other.

Again, thanks for writing another great article. I just hope that more people will visit your site. There’s too many confusions going on about “cholesterol.”

How true is it that our body has a feedback loop that prevents the body from storing dietary cholesterol?