The following is an excerpt from The Women’s Book. Specifically it looks at the issue of meal frequency and meal patterning. Specifically it looks at the issue as it pertains to women, who often face issues that males do not.

Table of Contents

Chapter 13: Meal Frequency and Meal Patterning

In the last chapter, I looked in a great deal of detail at concepts related to setting up what I consider an optimal diet. This included a look at general dieting concepts along with information about setting protein, fat, carbohydrate and sodium/potassium intake. I also looked at fluid intake and artificial sweeteners.

Having set up a diet, there are additional issues that need to be addressed such as meal frequency and overall meal patterning (on a given day) and calorie distribution (over the course of the week). I’ll look at each in some detail including some relatively “new” approaches that may be superior under some conditions. Finally I’ll end this chapter by looking at a question that most may have never considered.

Meal Frequency: Myths and Misconceptions

The first topic I want to discuss in this chapter is meal frequency, how many times someone eats in a day. This is yet another area where there is a number of myths and misconceptions and where many old ideas about what must be done for health or fat loss turn out to be generally incorrect. The general idea is that a high meal frequency (typically 6 times per day depending on where you look) has enormous metabolic and other benefits and that you must eat this frequently for optimal health and fat loss.

The idea is repeated endlessly and entire books have been written about the idea of eating every few hours and obsessed individuals will often put themselves into a truly pathological state to adhere to this supposed perfect meal frequency or spacing. You hear of people sneaking away from their workstation to eat in the bathroom or skipping social events or going out for the same reason.

One of the most common claims is that eating more frequently stokes the metabolism, based on the thermic effect of food and slight increase in metabolic rate that does occur with eating. But remember that TEF is related to the amount of food eaten during a meal (and estimated at 10% of total calories on average).

If someone is eating 1800 calories per day, their TEF will be 180 calories. If they eat six three-hundred calorie meals, the TEF per meal will be 30 calories, or 180 total. If they eat 3 six-hundred calorie meals, the TEF per meal will be 60 calories, or 180 total. Put differently, for the same total amount of calories, there is no impact of meal frequency on the total TEF or energy expenditure.

Another common claim is that skipping a meal, or even going too long between meals, will put the body in a starvation mode where it hoards calories and limits fat loss (or even slows metabolic rate). This belief seems to be especially prevalent for breakfast where claims that skipping breakfast will induce starvation mode or eating breakfast will “stoke the metabolism” all day. The latter is just another misunderstanding of TEF and I’ll address breakfast in more detail below.

The idea that skipping a meal causes a drop in energy expenditure or “starvation mode” came out of early animal research on mice and rats and certainly it’s true that even short periods without food do cause this to occur. But it’s critical to realize that small animals have a very short lifespan, mice live about two years and rats perhaps three times as long. These animals also don’t carry much body fat so even a slight caloric deficit can be very dangerous indeed (in some very small animals, missing a single meal can cause death).

What this means is that a single meal or day’s eating for these animals is a much more significant portion of their life than it is for a human. A meal for a mouse might be the equivalent of a day or more’s eating for a human; a day without food is probably equal to 4-7 days.

Human metabolic rate doesn’t even begin to slow with 3-4 days of total starvation and some studies find that it goes up a little bit. A single meal means nothing and even a single day without food won’t noticeably affect anything (recall that it takes the brain 3-4 days to even notice the drop in leptin).

It’s almost universally stated that eating more frequently either increases fat loss or spares the loss of lean body mass (LBM) while dieting but this really only holds true for extreme differences in meal frequency and even then only when dietary protein intake isn’t sufficient. When protein intake is high enough, meal frequency becomes more or less irrelevant. Anyone following the guidelines from the last chapter will be eating sufficient protein.

And research clearly shows that any meal frequency between 3-4 times per day shows no difference in either fat loss or LBM maintenance. While I’ll talk more specifics in the next section, individuals should pick the meal frequency that best suits their personal needs and preferences.

Any idea that there is a required or optimal meal frequency is simply incorrect. And as I’ll discuss below, there may actually be reasons for some dieters, and especially lighter female dieters to use a lower meal frequency than the normally recommended six per day.

There are some other claimed benefits to a higher meal frequency including keeping blood sugar stable or keeping people fuller. The first has usually been tested with completely unrealistic meal frequencies, often comparing 3 larger meals to 17 tiny meals. This has no relevance on normal eating patterns. Even the issue of hunger is debatable with one recent study finding that eating more frequently actually made people hungrier (3). Eating more frequently also didn’t increase fat burning.

Meal Frequency: Practical Aspects

Hopefully it’s clear that there is no magic to a high meal frequency for either general health, fullness or successful fat loss. But one idea that is rarely considered is that a lower meal frequency might actually be superior at least in certain situations.

A primary reason for this is recent work suggesting that meal size it an independent factor in determining whether it is filling or not; that is, this works outside of the hormonal factors I’ve discussed. Effectively, meals that are too small may not be as filling as meals that are larger; the mechanism behind this is currently unknown.

But this raises a critically important issue for smaller females, and especially when they are on reduced calories and dieting. With fewer calories to work with, a high meal frequency ends up making each meal almost insignificant in size. So consider our sample female dieter on 2000 calories/day. At 6 meals per day, each meal is just over 300 calories. At 4 meals per day, each meal is now 500 calories.

While both may be workable, eventually her caloric intake may come down and many females find themselves on 1400-1600 calories per day at some point in the diet. At this point, 6 meals per day makes each meal between 233-266 calories per day. A female at 1200 calories/day would be eating 200 calories per meal. And this becomes hardly a meal and certainly not a satisfying or filling meal almost no matter what food choices are made.

If these situations were moved to 3-4 meals per day, or 3 meals and a snack, that would raise the calories per meal to 300-400 or so which at least allows for a decent sized meal and amount of food. This allows for each meal to contain some amount of protein, vegetables, some fat and a small amount of other digestible carbohydrate to actually make the meal filling.

In contrast, switching to 3-4 meals, or 3 meals and a snack or what have you makes the meals 350-400 calories which is a meaningful amount of food. Even on 1200 calories, 3 meals and a snack mean each meal can be larger relatively speaking. This allows for the meal to contain adequate protein, some type of carbohydrate, vegetables and enough dietary fat to actually keep the meal in the stomach and maintain fullness.

Once again, this is an issue that larger males with a higher energy expenditure may simply not run into. Dieting on 2000 plus calories makes it far easier to maintain a higher meal frequency while keeping each meal much more satisfying. Splitting their meals into 6 has much less of an impact on meal size than it does for generally smaller females.

I should mention that one place where higher meal frequencies is often superior or even required is for highly active athletes who have a very high energy expenditure. This usually means highly trained athletes doing a large volume of training. To avoid making each meal uncomfortably large, a higher meal frequency can be superior here. Even while dieting, since they are typically eating more, very active athletes may be able to maintain a higher meal frequency (if desired).

Ultimately, given that there is no inherent benefit to a higher meal frequency in terms of metabolism, fat loss or much of anything else, readers should pick the meal frequency which works best for them in terms of their lifestyle, hunger, energy levels, mood, etc.

Realistically, smaller females are likely to do better with fewer but larger meals unless their energy expenditure is very high. Larger females, or highly trained athletes, may find a higher meal frequency to be superior. So long as at least three meals per day with adequate protein are being consumed, it really doesn’t matter beyond this.

Which brings me to the next topic, that of meal patterning, which actually interacts with the meal frequency discussion from above.

Meal Patterning

Meal patterning refers to how the day’s calories or meals are distributed throughout the day and clearly this will interact to some degree with how many meals are being eaten. This topic can get fairly complicated and an enormous number of patterns have been successful for one person or another; that alone should indicate that there are no absolutes here.

Certainly some approaches to meal patterning may be relatively better or worse for a given situation but readers must really get away from the idea that some specific pattern must be followed. I’m going to look a at a number of commonly used patterns and will be assuming a daily intake of 2000 calories across four meals per day. All that will differ is in the way that they are distributed.

Even Distribution

Probably the most common meal pattern is a simple even distribution with the day’s calories spread relatively evenly across the day. So a four meal even distribution might mean eating at 8am, 12:30-1pm, 5pm and 8pm and generally speaking every meal would have roughly the same distribution of protein, carbohydrate and fats (within a similar range in any case).

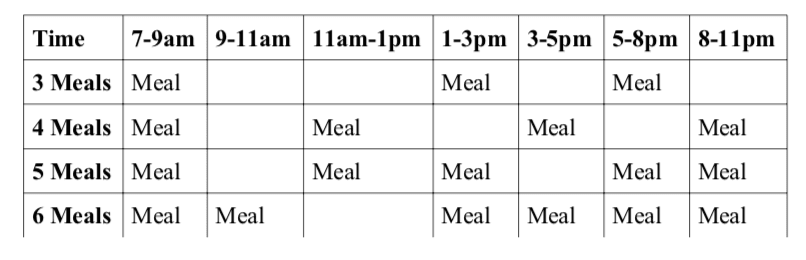

This types of distribution convenient for many since it fits the normal work day schedule (the 5pm meal may be a problem) and can even accommodate an evening workout in between the third and fourth meal. While convenient, there are actually some very good reasons for most people to use some type of uneven distribution of their daily calories. I’ve shown some even meal frequency patterns based on 3-6 meals per day below.

Uneven Distribution

By definition, any other meal or calorie pattern that isn’t an even distribution if an uneven distribution. Here things can get very complex as both how meals and the day’s calories are distributed across a day can vary. So potentially any given meal could have different amounts of protein, carbs, fats, etc. While the specific amounts can vary, I generally think that every meal (or perhaps eating occasion) should contain some amount of each nutrient although this may not always be possible.

A piece of fruit isn’t really an appropriate meal for the most part and neither is any other single nutrient with the possible exception of protein. Except around a workout (see below), try to get some of each of the major macronutrients at each meal (even a meal of protein, vegetables and some dietary fat technically

In the general public, probably the most common uneven distribution would be three primary meals at breakfast, lunch and dinner with one or two snacks in-between. So for a fairly typical 9-5 type of job, that might be breakfast at 7:30am, a snack at 10:30am, lunch at 1pm, a snack at 4pm and dinner at 7-8pm or something in that range. The best way to set up this type of distribution would be to subtract out the snacks and then determine the size of the other three meals.

So our sample dieter with 2000 calories daily might factor in two 200 calorie snacks, leaving 1600 calories across the other three meals. That would leave 530 calories per meal which should be nice and filling. Since the smaller snacks are coming at a little bit higher frequency, any issue with fullness should be mostly avoided. I still recommend each snack contain some amount of protein, carbohydrates, fiber and fat if at all possible.

This is a place where protein bars or pre-packaged liquid meal replacements may be especially useful although they are not always the most filling. A single serving of low- or medium-fat yogurt (ideally with some type of fiber powder thrown into it) would contain protein, carbohydrates and some fat along dairy calcium and there many other options that can be worked out here.

Larger Evening Meals

One type of uneven distribution that may be very worth considering is one when relatively larger meals are eaten in the evening. Yes, there is still a myth floating around that larger meals at this time magically turn to fat but that isn’t the case on any level.

And this type of approach may have a number of benefits, once again especially when dieting. A majority of people work during the day and since that keeps them busy, they often aren’t that hungry. Or, perhaps more accurately, are distracted from eating by other things.

As well, nighttime when most people are home, bored, not busy can be a problematic time from an eating standpoint and nighttime hunger can be a real diet breaking issue. Shifting more of the calories to the evening during this time can have a number of benefits. It allows for a larger meal to be eaten at dinner which may be helpful for folks with families so they don’t have to eat a tiny diet meal while the rest of the family is eating normally.

As well, larger meals and/or relatively more carbohydrates at night-time can help with sleep issues. Not only aren’t dieters not trying to go to sleep hungry, the carbohydrates tend to affect brain chemistry (primarily serotonin which helps with sleep).

Some have even taken this to the extreme where predominantly protein, vegetables and some fat are eaten during most of the day while most carbohydrates are eaten in the evening. Women, due to their tendency to have blood sugar issues (especially during the luteal phase) may want to put in some fruit earlier in the day.

For older individuals, there may be even more potential benefits. There is evidence that, with age, skeletal muscle becomes relatively more resistant to the effects of dietary protein on skeletal muscle metabolism and this contributes to the age-related loss of muscle (sarcopenia) that can occur.

A strategy called protein-pulse feeding, with as much as 70% of the day’s protein intake at one of the meal’s of the day (the other 30% is spread out) has been shown to have benefits here (4) and this might be worth considering as women approach menopause. I doubt it has to be done at this extreme but putting proportionally more protein in the evening meal may be worth considering. Note that this has not been shown to have benefits in young people with a more evenly spread out protein intake is superior.

For women who train in the evenings, there are other benefits to putting relatively more calories in the evening which brings me to the next topic.

Around Workout Nutrition

Although the meal patterns described above are appropriate for the general public, those involved in exercise training and especially weight training have another issue to consider which are any calories and nutrients consumed around a workout. I mentioned this briefly when I talked about athletes increasing their caloric intake on training days by putting extra calories after their workout but want to go into more detail.

I should mention that while beneficial, this is not as important as it was once thought. The idea that there is some magic post-workout “window” for eating that closes after some period of time turns out not to be completely accurate (5). At the same time a considerable amount of research shows that post-workout protein helps to improve adaptations; it will rarely hurt to consume at least some nutrients following resistance training.

However, under certain conditions, it’s clear that post-workout nutrition may be relatively more important. One of these times is during fat loss dieting. Part of the reason that lean body mass (LBM) is lost is due to changes in hormones which negatively impact on skeletal muscle metabolism. Protein synthesis (building muscle) decreases and protein breakdown increase. And the combination of proper resistance training with post-workout protein effectively reverses this (6).

Perhaps, surprisingly, this is a place where there are no major gender differences in terms of what types of nutrients should be consumed for recovery; the only difference is in the amounts due to differences in body size (7). Smaller females in heavy training will simply need proportionally less after a workout to stimulate recovery than larger females or generally larger males.

I mentioned above and throughout this book that at menopause, women start to suffer from sarcopenia and there is currently a large degree of interest in how to reverse this. And one factor is the combination of proper resistance training along with dietary protein, both intakes above normal and some consumed right after training (8).

For all of these reasons, consuming some nutrients and calories after training would be ideal for those involved in resistance training. For the most part, unless the duration or intensity of an endurance/aerobic type of workout is very high (as would be seen in performance athletes), this type of post-workout nutrition isn’t required.

At the very least protein, and ideally protein with some carbohydrate should be consumed after training; carbohydrates by themselves are not optimal. This combination has an additional benefit for smaller women; adding protein to carbohydrates improves the storage of carbohydrate in muscle without having to eat as many carbohydrates. Calories can be kept lower while still obtaining the same recovery benefits. Athletes who are not restricting calories or who have a very high energy expenditure can consume more carbohydrates here.

It’s been debated for quite some time what optimal post-workout nutrition might be. There is some indication that whey protein, a type of dairy protein that is very quickly digesting, may be the best post-workout protein. This may doubly true for older individuals as the fast digestion speed may overcome the resistance that skeletal muscle can develop. Women approaching menopause should consider supplementing with whey protein after resistance training; this will also help to bump up total protein intake.

A typical amount of post-workout nutrition for women might be in the realm of 100-200 calories with 20-25 grams of protein (80-100 calories) and another 20-25 grams of carbohydrate (80-100 calories) if they are consumed. Many find that they are not very hungry after an intense workout and liquids are often superior here. Various commercial products are available with different combinations of protein and carbohydrates and I’ll talk about protein powders briefly in Chapter 15.

But there may be a much more convenient form of post-workout nutrition which is nothing but good old fashioned milk. Although only a portion of the protein in milk comes from whey, it’s looking like it might represent an optimal post-workout drink, improving recovery and helping with rehydration.

One eight ounce glass of milk will contain 80-120 calories, 8 grams of protein, 12 grams of carbohydrates and variable amounts of fat and perhaps double that amount of calories would be optimal. This would also provide dairy calcium and Vitamin D. If you don’t want to drink that much fluid at once, 8 oz of milk with one half scoop of whey protein and a half piece of fruit would provide a nearly ideal post-workout meal with ~20 grams of protein, 25 grams of carbohydrate with a little bit of fructose.’

And, getting back to the topic of meal patterning, the above is importance since the inclusion of at least some nutrients after a workout means that the overall patterning of the day will be changed at least somewhat. The first thing that needs to happen is that any post-workout calories be subtracted from the day’s total.

So let’s say that our 2000 calorie/day dieter is consuming 200 calories (25 grams protein and 25 grams carbs) after training leaving 1800 calories for the rest of the day. Across four other meals, that allows each to be 450 calories if they are distributed evenly although they could be distributed even more unevenly as desired.

As I mentioned above, assuming an evening workout, putting more calories in that time period, some immediately after the workout and a larger dinner meal while consuming relatively less calories earlier in the day may provide not only recovery benefits but also help with sleep, etc. while dieting. Note that many athletes perform more than one workout per day and calories will probably have to be spread out more.

The Issue of Breakfast

Having looked at post-workout nutrition and suggesting that putting relatively more calories in the evening may have a number of benefits, I want to address another fairly pervasive idea which has to do with the relatively importance of breakfast.

I mentioned in the section on metabolic rate that the old idea that breakfast stokes the metabolism or that skipping breakfast puts the body into a starvation mode are both nonsensical as the body doesn’t adapt on a meal-to-meal basis like this.

But there is also quite a bit of observational research that folks who skip breakfast are fatter and this has been interpreted as saying that skipping meals makes you fat. But there is a problem here with cause and effect. Just as with the use of diet products, many people start to skip meals after they have gained weight. But it wasn’t the meal skipping that caused the problem.

Certainly for some people skipping meals can cause them to be hungrier later in the day; if this causes them to eat more than they otherwise would during the day. But research typically shows the opposite, that even if people eat slightly more later in the day, their total daily calorie intake goes down when they skip breakfast. Even if someone eats 200 calories more later in the day, if the skipped breakfast would have been 500 calories, they have still eaten 300 calories less that day.

And while it is often found that those who eat breakfast perform or think better, and this is especially seen in children and school performance, there is an adaptation issue. After a few days, people get used to not eating breakfast. When you feed someone who normally skips breakfast a meal, they perform worse and when you make a normal breakfast eater skip breakfast, they also perform worse.

For female dieters, especially smaller females, with fewer calories to play with, often clustering their calories later in the day can give them even larger meals. People who work a day job are often busy enough to not get hungry and even caffeine or one of the stimulants I’ll describe in the supplement chapter usually make appetite go right away.

As I mentioned above, moving more calories to the evening time when hunger is worse goes hand in hand with this. Skipping breakfast entirely saves more calories for later in the day; when dieting for fat loss this can be enormously beneficial when there isn’t that much food to be eaten.

Intermittent Fasting (IF) Variations

At the most extreme of the above uneven distribution patterns is a relatively new approach called Intermittent Fasting or IF which basically refers to going longer without eating anything prior to breaking the fast. Once again, this doesn’t slow metabolism or cause starvation mode and one of the earliest studies that gave the day’s calories in a single meal actually showed a slight fat loss.

There is emerging evidence that this type of approach, or the use of occasionally longer fasting periods may have a number of health benefits as the light stress that this causes stimulates the body to improve various aspects of health. IF actually spans a number of different interpretations and I’ll look at them below.

Related to the idea of IF’ing, which typically refers to a single day, there is a related idea called Alternate Day Fasting (ADF). This described a situation alternating an entire day of fasting (strictly speaking this is usually 25% of maintenance calories but it’s still called fasting) with the in-between days at maintenance or above. Generally folks end up eating about 10% more than normal but the overall effect is still a lowered weekly caloric intake.

As I mentioned in a previous chapter, the body doesn’t really respond that quickly to lowered calories and alternating in this fashion might represent a superior away to generate a large weekly deficit (for fat loss) while avoiding some of the hormonal problems. And it might very well help the normally cycling woman to avoid the problems inherent to extended periods of low energy availability on menstrual cycle and hormonal function; this has not yet been studied but I don’t see why it wouldn’t have that effect.

And so long as an ADF pattern doesn’t cause the free eating days to be massively over maintenance, this can cause the overall weekly deficit to either be larger or at least more or less identical to what would be seen with a straight reduction in calories.

Related to ADF if a dietary approach that is being called Intermittent Caloric Restriction (ICR); this refers to alternating longer periods of fasting (again usually 25% of maintenance calories), perhaps 2-4 days with periods of normal eating. ICR has actually been found to cause the same fat loss as straight caloric restriction while sparing LBM loss.

This is also effectively the same approach I described when I talked about how the normally cycling woman can avoid menstrual cycle and hormonal problems; by raising calories to maintenance every so often, the typical hormonal adaptations are reversed or at least lessened.

In any case, dieting for a few days harder than normal and then raising calories might be superior in the long-term to a straight caloric restriction approach to fat loss for various reasons. It may spare LBM loss, avoid some of the normal metabolic adaptations, and could potentially improve adherence.

Once again, it’s no different than my overall recommendation for dieters to raise calories to maintenance in the first place. But the key here is that the lower-calorie/harder diet days must be alternated with calories being raised to maintenance even slightly above. Many women are hesitant to do this and, in the long run, that causes the problems I’ve talked about previously.

I’ve shown the different patterns that I described below to show how the weekly deficit can be the same or larger with the different approaches. IF’ing really just describes a different daily meal pattern and I’ll still assume the same weekly deficit. It can easily be combined with the ADF/ICR types of approaches. So even eating later in the day, calories could be varied from lowered/very low along with the shift in how the calories are distributed throughout the day. But you can see that the ADF/ICR approaches can actually generate a greater weekly deficit than straight CR.

“Fasting” here means 25% of maintenance calories which may be too low in some cases if it means insufficient protein. “Ad-lib” just means eating “normally” (whatever that means) and researchers typically assume 110% of maintenance on those days. If calories are kept at 100% maintenance, the effective deficit for IF, ADF and ICR will be even higher.

IF/ADF/CR for Lean and Active Individuals

It’s important to realize that ICR has only been tested in obese, non-exercising individuals and some modifications (primarily higher calories on the fasting days) would have to be made. The more athletic approaches to IF’ing generally revolve around 3 meals that are clustered around an evening workout.

So a small meal might be eaten an hour or two before the workout, calories being eaten immediately after training, and then a fairly large dinner meal. The single meal IF approach is not really appropriate here. Make no mistake that IF is not magic for fat loss. Calories still have to be tracked and those seeking fat loss still have to create a daily deficit.

Athletic IF approaches tend to be ideal for trainees who work out in the evening (and they may be wholly inappropriate for performance athletes who train more than once per day). It is more difficult to apply this for dieters who work out in the morning since it typically means eating earlier in the day and having to contend with night-time without food. It can be done but it’s more difficult, most of the food is clustered earlier in the day which still leaves a potentially problematic evening time in terms of hunger, sleep, etc.

As well, since IF’ing is really more of a meal distribution pattern, it can be further combined with an ADF/ICR type of approach. Years ago I described what became known as an Every Other Day or EOD dieting pattern where calories were higher on heavy training days and lower on easier or low-intensity training days.

For a Monday/Wednesday/Friday training pattern, calories would be set a lower level (50% of maintenance, an aggressive deficit) on Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday/Sunday with more calories on training days. Since carbohydrates will have to be reduced fairly significantly, the low calorie days might be nothing more than proteins, some vegetables with a small amount of fruit and dietary fat. Carbohydrates and calories would be increased on training days.

So far as ICR, my own Ultimate Diet 2.0 actually used exactly this pattern (a decade before it was studied) where calories were set at 50% maintenance for nearly 4.5 days (generating rapid fat loss) followed by 2.5 days of higher calories. It was aimed at Category 1 dieters and allowed many to either maintain or even gain some LBM while dieting and some women dieted down without a loss of their menstrual cycle. Even for Category 2 and 3 dieters, I have recommended periods of higher calories/carbohydrates (termed refeeds) for years.

Even performance athletes who are doing different types or amounts of training may benefit from this type of dietary strategy, putting more calories on harder training days and reducing them on the lower intensity days; the deficit wouldn’t be as large on training days here. Just adjusting their caloric and nutrient intake based on the day’s actual energy expenditure. High-intensity performance athletes often have very hard training days with sprints and weight training alternated with lower intensity days.

As well, those athletes seeking gains in muscle mass or strength/power could use this type of approach without much if any deficit. Calories would be set slightly above maintenance, 10% above is more than sufficient with calories at maintenance or slightly below maintenance on easier training days. This can help to avoid the fat gain that can occur during gaining phases without hampering overall recovery or adaptation.

Perhaps the easiest way to do this is to set up the baseline diet to be used on non-training days (using the math from the last chapter) and then add calories on training days with around workout nutrition to match the workout. So a performance athlete burning an extra 300 calories on heavier training days just needs to add that around a workout to support training. This is one huge benefit trained athletes have over everyone else; their ability to burn a lot of calories during workouts allows them more total food intake overall.

Once again, the EOD and ICR approaches almost match the weekly deficit of the straight CR approach with a far different pattern of caloric intake and a less stringent diet. Once again this improves recovery and training performance on those days while still generating fat loss and potentially avoiding menstrual cycle and other hormonal dysfunction that happens with straight dieting. The EOD approach for gaining generates an effectively insignificant deficit but it doesn’t generate the surpluses that can often lead to fat gain either.

Some Concerns about Intermittent Fasting

Now, a number of fairly silly arguments have been made against IF’ing for women, typically revolving around the single meal per day approaches. For female athletes or even who are involved in any type of heavy resistance training, I do not recommend that approach and the type of athletic IF application I described above would be more appropriate.

At the same time, some women do find that extended fasts, past about 14 hours can cause their blood sugar to become unstable causing mood and energy problems (and this is especially true during the luteal phase. A slightly shorter fast of hours and the inclusion of some fruit at the first meal goes a long way towards preventing this.

So a woman who ate her last meal at 8pm might break her fast with a small meal at 2pm. It doesn’t have to be large and could be followed with another small meal at 4 or 5pm for an evening workout. Calories would be eaten after workout and then a larger dinner meal would be appropriate.

On 2000 calories per day, a snack of 300 calories at 2pm, another snack of 300 calories at 5pm, 200 calories after training leaves 1200 calories for dinner time. Which might even be excessive and more could be put in either the 2pm or 4pm meal.

As calories drop lower, this can be even more useful. On 1600 calories, for example, the same meal pattern would leave 800 calories at dinner time (or even 600 calories for dinner and a 200 calorie pre-bedtime snack to stave off nighttime hunger and help with sleep). IF’ing can be a powerful strategy here.

I’d also add that there is one population that I think should not use IF’ing (despite it’s proponents, typically men, thinking that it’s the solution to all problems) and that is any female with a previous eating disorder (bulimia moreso than anorexia but both can be problematic) or even those with a tendency towards disordered eating patterns.

In this situation, IF’ing, ADF or ICR types of patterns can put them right back into the type of purge/binge cycles that they had in the first place. It turns into a starve all day (or every other day) alternated with a complete loss of food control.

Even dieters not coming from that background often find that they lose total food control in the evenings when they fast even part of the day. Starting the first meal with protein and fiber can help with this but it can still cause problems. This is a very individual type of thing with no absolutes.

Whether for athletic applications or the general public, I’d suggest trying IF’ing (or any other dieting approach) at most three times and if it simply doesn’t work, it should be abandoned. A straight caloric restriction approach with calories being raised to maintenance every so often may be the superior approach here.

Even more information about this topic as it pertains to women can be found in The Women’s Book

Facebook Comments