The post I’m going to make today is something I’ve not only wanted to put down for a while but was originally written for a monster book on fat loss that I started last year (which is 95% done and from which The Women’s Book sprang). Since that book focuses on fat loss, most of the language deals with that topic. But it would generally apply to behavior change overall. I’ve changed some of the text and verbiage for various reasons.

Table of Contents

Behaviorism

An older idea of human behavior (called behaviorism) suggests that we do things either to obtain reward (things feel good) or avoid punishment (things feel bad). While there is obviously more to it than that in humans, there is no doubt that these types of pathways play a role in human behavior.

Humans tend to do things that feel good/reward them (like eating) and avoid things that feel bad/punish them. In fact, we are fairly hardwired (deriving pleasure) to engage in activities that make us feel good or reward us (like eating, sex, etc) since those are important beahviors to keep us alive.

It’s not coincidence that most of the “bad” behaviors that people engage in, sex, gambling, smoking, drinking, drugs or overeating tasty high-sugar/high-fat foods drive the reward system in the first place. We do them because they are fun, feel good, make us feel better (at least temporarily), etc.

If we didn’t, we wouldn’t do them. Which raises a reverse question, why do some people engage in what seem like miserable activities (such as intense painful exercise training or restricting themselves from tasty foods) and that I’ll come back to.

Technically you can addict or mis-use any of the above and more. There are sex addicts, gambling addicts, drug addicts, alcoholics and I talked about the concept of food or eating addiction earlier in this book. It’s clear that some people are more or less predisposed to become addicted to anything, there is a clear genetic component and it probably resides in the reward system and the same system may be involved in food intake and obesity.

Someone who starts out with a differentially wired reward system will respond enormously to that one thing that then becomes their behavior of abuse. And, as it turns out, constant use of that compound ends up having long-term negative effects on the system.

What started out as hugely rewarding becomes less so with time which is why people have to keep escalating their use. And this type of variability has been clearly shown in those predisposed to obesity. But this brings us to one of the biggest problems with traditional dieting (here again I’m assuming the typical approach to dieing based on a fairly absolute approach to food intake)

Cravings

Whenever people try to stop engaging in behaviors that they are “addicted” to they go through cravings. There are probably several reasons for this. Part of it is simply wanting what you can’t have. Assuming you like something or doing something, if you are told you can’t have it or do it again, you will want to. Humans are just weird that way although it tends to only hold for things we enjoy. Most wouldn’t crave, say, asparagus if you told them they couldn’t ever eat it again. But a cookie?

There is also a clearly biological aspect of it, when a reward system has gotten “used” to a given level of stimulation, removing that stimulation makes them feel bad. Even drug addicts and alcoholics who may have originally gotten high from their substance of choice often reach a point where using is necessary just to feel normal. Take the drug away and they feel bad and go through withdrawal (rats who have been “addicted” to sugar or fat show the same types of symptoms).

But there is another issue which has to do with the environment and there are a couple of issues here. One is that habits and behaviors are driven more automatically than most people want to realize. If waking up always means a cup of coffee and a cigarette, then waking up will trigger those behaviors without thought. If someone typically gets a treat from the vending machine on the way to the bathroom at work, the vending machine will become a trigger to get a treat. Simply seeing the vending machine will trigger the craving.

There’s a second way that environment can trigger a cravings beyond that. Because cravings can be triggered not simply by deprivation or biology but by interaction with a substance of choice. Studies of drug users show that a part of their brain involved in emotional memory lights up when they are shown videos of someone else using; that triggers a cravings.

Smokers will report a craving when they around other smokers and alcoholics often have to stay away from people consuming alcohol for the same reason; the sight of it will trigger a craving. For people trying to stop these behaviors, it often means cutting themselves off from a previous group of associates, simply to avoid the triggering environments.

And of course food intake is the same, the sight (TV commercial or billboard) or sensation (smell) of a tasty food can trigger a desire to eat; this is why places that sell food often waft odors of the food, pizza or cookies, to trigger people to want the food whether they are hungry or not.

This is one of the problems dieters run into being around people who are enjoying these kinds of treats; watching someone else eat them can trigger a craving. A lot of successful dieters cut themselves off from such situations completely. It is effective although it’s questionable if it’s terribly emotionally or mentally healthy (then again, everyone successful at any venture does this to one degree or another; successful athletes don’t miss training to go to a party and successful businessmen lose friends, family, etc. in their quest for money).

This is already worse in people with a reward system that is overactive/desensitized and gets worse with dieting due to the physiological changes which are occurring with dieting. Cravings also occur in leaner dieters and this is frequently made even worse by exceedingly restrictive diets. The more extreme the diet, the more foods it eliminates, the worse and more frequent the cravings become.

It’s also a place where, again, dieting is at a huge disadvantage to other behaviors. An alcoholic can avoid alcohol, a smoker can avoid people smoking, drug addicts can avoid the environments or people that they used in or with. But a dieter can’t avoid food. You also don’t have to smoke, drink, take drugs to survive; you have to eat. It can’t be avoided in the human experience.

Food Cravings

We can simply define a food craving as “an intense desire for a specific food, drink or even taste (i.e. something sweet.”. Both intensity (weak, moderate, strong) and specificity towards a specific thing. This can’t be measured terribly well in research and typically is based on self-reported desire or by using some type of numerical scale (i.e. rate your craving from 1-100).

Not shockingly, most cravings are for sweet and sugary foods with chocolate leading the list, other sweets next and cereals and other carbohydrates third. Few seem to have cravings for meats and protein based foods although there is a gender based difference in this. Women tend to crave carbs/fats and men crave meats/protein.

But it also appears that dieters crave foods that are different from what they are eating, although this is not surprising. In one fun study, subjects fed a sugary sweet nutritious diet made them crave whole foods. They wanted something different than what they were eating. Low protein diets tend to make people crave protein foods and low-carb diets make people crave carbohydrates. And of course bland monotonous diets make people crave the tasty foods they used to eat.

And clearly this is a real problem with food cravings occurring to relatively more or less a degree in different individuals. But they do occur. And I think the fact of cravings, the nature of dieting itself, the way that humans respond to reward and punishment leads me to explain the title of this chapter.

What Does This Have to Do with Dog Training?

I had the pleasure of spending about 2.5 years working with and training rescue dogs at the Austin Human Society a while back and, as it turned out, learning how to best train them led me to delve deeply into the research on rewards and punishment in how it determines behavior. Of course, I had an interest in this to begin with since it relates so much to dieting but it ultimately led to this section of the book.

Although the topic of behaviorism gets much more complicated than this, I’m going to keep it simple and talk very simply about rewards and punishment. You can think of a reward as anything that makes us feel good.

It can be eating something tasty, doing something that feels good, seeing the numbers on the scale go down or having clothes feel looser can also be rewarding within the context of dieting. Punishment are things that make us feel bad. In the context of dieting, this means being hungry, going through an unenjoyable workout, no being able to eat the foods you used to eat or having a craving that you can’t fulfill.

In general, we perform rewarding behaviors more frequently and punishing behaviors less frequently. If eating a piece of candy is rewarding (and reward here has to do with the brain’s response to it) then we will tend to eat more candy.

If eating asparagus makes us want to gag (a punishment), we will tend to eat less asparagus. If exercise makes us feel better, good, or we enjoy it and it is rewarding we tend to do it more. If it makes us miserable, or causes injury or excessive soreness which most will see as punishment, we tend to do less of it.

Parents try to shape their children’s behavior similarly: rewarding good behaviors and punishing bad behaviors. Good grades and they get to play video games, break something and they get sent to their room. Sometimes it even works. Humans, unlike animals can choose or reframe reward and punishment in amazing ways (consider someone who gets sexual pleasure from being flogged, what most would consider punishment they consider reward. In this case punishment would be to NOT flog them.)

Timing of Reward or Punishment

In most animals, things that are immediately rewarded or punished tend to have the greatest impact. With dogs, if you don’t give them the reward or punishment within about 0.5-1 seconds of an act, it has no real impact.

Dogs can’t connect the behavior with the reward/punishment if you take longer than that. It’s why punishing a dog when you come home and he pooped on the floor is ineffective, he has no idea what he’s being punished for. It only works if you catch him peeing on the floor and punish him immediately.

And spare me the argument that he looks guilty. He is responding simply to his human’s emotional state. You see the poo, you get mad, he senses it and looks sad. Dogs don’t feel guilt (don’t start me on this idiot dog shaming thing online. Not only can they not read, they don’t feel shame in the first place).

Humans are a little bit different here. Our brains allows us to associate a behavior now with a delayed reward or punishment. So if you send someone a wedding gift and three weeks later get a thank-you card, you can connect those two behaviors logically.

You don’t think the thank-you card is related to something that happened a half-second ago. If a child does something wrong and gets punished when their parent comes home hours later and is told why they are being punished, they can connect those on some level. However, rewards or punishment that happen closer to whatever is being rewarded or punished still has a stronger impact in the big picture. So let’s look at how this applies to dieting and fat loss.

Dieting and Fat Loss

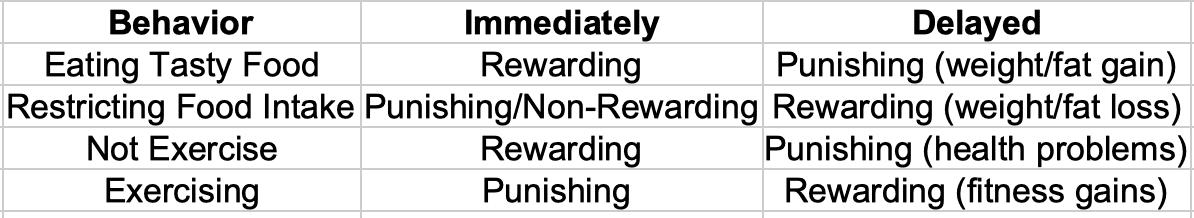

I’ve provided a lot of reasons why diets fail but here I want to look at a problem that exists at a conceptual level in terms of the concept of reward and punishment. The same actually goes for the effects of exercise programs and the combination of the two is just a double problem. Because as you’ll see the entire concept of both has a reward/punishment structure that is exactly the opposite of what it should be to get people to stick with the goal behaviors.

Consider that if every time you overate you woke up or immediately got fatter; I mean you visually saw yourself gain fat right then. That is, the negative aspect of eating that food came immediately after the act. Assuming you see getting fatter as a punishment, you’d be likely to stop doing it.

But that’s not what happens; in fact what happens is exactly the reverse of that: eating the food is immediately rewarding while the visible or measurable weight/fat gain is delayed. Even if it shows up on the scale in the morning (due to water or what not), it’s still delayed relative to the immediate reward that it produced.

This is why some approaches to behavior change with overeating and drug use have used compounds that cause people to get sick immediately. It’s an attempt to link the behavior with an instantaneous punishment to break them of the habit. If eating a cookie makes you vomit, you probably won’t keep doing it. But it’s a pretty awful way to go about it. And for reasons I forget, I don’t think it worked very well.

For people who don’t enjoy exercise, the same dynamics hold: not engaging in an activity that they don’t enjoy is immediately rewarding but any negative effects and punishment in terms of health problems may not show up for years.

If every time someone didn’t exercise they felt physically worse, they would be a hell of a lot more likely to do it. This does often reverse for folks on established exercise programs, not training makes them feel guilty, stiff or worse than they would if they had exercised but here I’m talking mainly about changing the behavior the initially.

In contrast, consider that if every time you started a diet, or even skipped that piece of cake at the restaurant, or went and exercised, you woke up or were immediately leaner and lighter. You’d be getting an instantaneous reward for your efforts (mind you the food is still pretty quickly rewarding). But that’s not what happens excepting the people who weigh before and after their workout to watch the numbers drop from dehydration.

When you get a craving or hunger and can’t fill that immediate need you feel deprived and there is an immediate punishment (you didn’t get to eat the food you wanted to eat). But the reward of weight/fat loss and improved appearance doesn’t happen for days or weeks later. Not eating what you want is immediately punishing and the rewards are very delayed. The benefits of exercise don’t show up until days or weeks after the workout itself, exercise is often immediately punishing and any rewards are delayed.

I’ve summed this up below.

Admittedly, in the initial response phase I talked about in the previous chapter (it was a chapter looking at the various phases of behavior changes all of which are subtly different), this is less of an issue. The initial phases of the diet are usually pretty easy and the results often happy pretty quickly.

This is one pretty large potential benefit both low-carbohydrate and very low calorie diets that induce rapid fat and weight losses. The immediate rewards for the behavior are almost instantaneously rewarded and this happens before the cravings and hunger start. Recall that rapider initial weight loss, done right, is actually associated with better long-term results.

But as the diet progresses and dieters enter the continued response phase the reversal in what should be ideal starts to occur. Cravings and hunger increase while fat loss is slowing down; the behaviors that were initially immediately rewarding without being terribly punishing are becoming more punishing for less reward.

Hyperbolically Discounted Marshmallows

There are other issues here, one of which is called hyperbolic discounting. Simply, humans assign different values to rewards (or punishment) depending on how soon they occur. Studies typically do something like offer someone $10 now or $100 in a month or some variant on that.

And even if it is completely logical to wait, many people don’t. $100 is always better than $10 but that’s not how people assign the values. This depends intensely on the amount of the values being compared and how soon or late they are. $10 now or $20 tomorrow, most will wait. $10 now or $1000 a month from now, most would probably wait. $100 now or $1000 a year from now? I don’t know, I haven’t read all the studies.

A related set of studies done in the 50’s looked at this in a slightly different way. They were done by a researcher named Mischel and dealt with kids and marshmallows. Simply, kids were told they could eat one marshmallow now or two marshmallows after some time. Obviously, two is better than one but there was huge variance in who did or did not wait.

Some kids showed a better ability to delay immediate reward and others didn’t (the kids who did used a bunch of strategies to avoid the temptation. One girl used her hair to cover her eyes). But of some interest, when they were tracked, the kids who showed the ability to delay immediate gratification succeeded in every aspect of their lives. We all know that guy who spends money he doesn’t have to buy stuff he doesn’t need, who skips studying to go to the party. And it usually cuts across every aspect of their life.

Of course, these are also kind of contrived studies. Logic or not, someone who is broke takes the money now no matter what benefit waiting might have. What if it was one marshmallow or $10 later on? Two tasty treats is always better than one tasty treat even if a lot of kids still choose one. But it all sort of goes to the issue that rewards that occur sooner often have much bigger pull than those that are further away due to the way the human brain represents them.

But I’m getting a bit off track (all of the above is discussed in endlessly more detail) And this is a very real problem but clearly some people are better or less able to deal with this effectively reversed reward/punishment situation . I’ll offer what a potential solution to at least part of this but for now I want to look at some of the ways that, mentally, dieters are able to maintain their focus in the face of the above.

Big Brained Humans

Unlike most animals, humans have big brains (that we sometimes even use) that give us the ability at least conceptually link immediate behaviors to long-term results. One aspect of successful dieters or athletes is their ability to reframe immediate discomfort (hunger, fatiguing exercise) as generating a long-term reward in terms of fat loss, increased fitness, or performance.

Athletes may spend a decade engaging in gruelling training all in the hope that it will pay off with an enormous reward in the long run and successful dieters probably do the same thing. This is the basis of Deliberate Practice I discussed in an earlier article series. People who are successful put time into what are immediately boring and tedious activities by tying them to long-term benefits. .

There are also some apparent oddities in human behavior later in the book that show that some people do just like that: temptation, hunger, etc. make them more determined to reach their goal. Many obsessed dieters will even talk in those terms. So you’ll hear them say that “Hunger is fat leaving the body” or “Sweat is fat leaving the body” or whatever.

They engage in cognitive reframing of short-term discomfort into a long-term reward to make sure that they focus on the long-term. It seems possible that trying to psychologically reframe the experiences of both overeating and restricting food intake could help with long-term adherence. In my experience, a lot of this seems to be pretty hardwired and difficult to change.

There’s an old aphorism is “A moment on the lips, a lifetime on the hips” which is a way of looking at overeating in terms of the negative; it links what would normally be a short-term rewarding experience with the long-term negative.

We might switch that to “Not putting it into your lips leads to thinner hips” or something equally silly to work in the opposite direction, to tie the short term punishment/lack of reward with the long-term benefits. Both have their place at different times and positive/approach reframing can work better in some cases (when trying to reach a goal) while negative/avoidance reframing works better in others (trying to maintain a goal). Again, other sections of the book this is from.

Personal Rewards

And I think this simple model sort of encapsulates the basic problem with behavior change and changing food intake/activity patterns overall. The dieter has to undergo some short-term deprivation and punishment to hopefully obtain the desired goal in the long term. And this is completely the opposite of what would be ideal. Ideally, the reward would come immediately and any punishment or lack of reward would be delayed. But fundamentally it’s not like that.

I would mention that other behavior change, such as smoking, is often reversed from dieting. When someone starts quitting smoking, the above dynamics hold: they feel miserable with few immediate rewards. But over time, it often gets somewhat easier.

They aren’t as punished for not smoking as the cravings dissipate and the rewards become more immediate/pronounced. Clothes don’t smell, they aren’t coughing up a lung every morning, they have more money, etc. Dieting is always the opposite; the rewards come slower as the effort becomes worse.

How Do we Fix This?

There are a few general ways to approach it (outside of some strict behavioral approaches).

I think that the temporal/hyperbolic discounting thing has a real implication for goal setting. If we know that goals that are further away than rewards close to us and that we assign a lower value to the longer term goals, setting only very long-term goals is a recipe for disaster.

Tell someone with a lot of weight to lose that “You can’t ever eat a tasty food again so that you’ll reach your goal in a year” and you’ve already lost. A year away is impossible when a cookie is here now. Hence the need to set immediate, short, medium and long-term goals. Set one for today. Set one for end week. Set one for a month from now. Set one for 3 months from now. Six months. A year. Maybe even forever.

It’s part of why I think breaking dieting into shorter blocks (interspersed with full diet breaks) makes more sense: dieting for a year or two straight is impossible psychologically. Dieting for 6-12 weeks is much more doable (moreso if those weeks are then broken up with other flexible dieting strategies).

I think there’s a good reason (and a real benefit) for group approaches that use a weekly weigh in (such as Weight Watchers). Knowing that you have to get measured/be held accountable in only a week’s time keeps the goal a lot closer to the forefront than it being months away.

A recent study even showed that daily weighing helped with the adoption of better health practices and better weight loss and I suspect that it worked by attuning people to their goals on a daily basis; not only did they have to weigh (which has its own sets of pros and cons) but it means starting every day with a reminder of their goals.

Related to that, there may be another way of approaching the problem, finding a way of providing some sort of short-term and immediate reward to help maintain the desired dietary or exercise habits. Food would be the logical choice but clearly there’s a problem there: rewarding an attempt to restrict or alter food intake by eating more food sort of defeats the purpose (even if many people will reward their earlier daily restriction or exercise by overeating later on).

If could possibly work if the treat is kept small and controlled (i.e. one piece of candy when you go to the gym). Just don’t fall into the trap of “I did my workout and earned that double cheeseburger” that I mentioned in the sections on exercise.

There are probably better approaches overall than using a food reward in an attempt to change a food related behavior at least acutely. Mind you, some of the flexible dieting concepts such as the free meal (a relatively normal non-diet meal that comes after multiple days of successful dieting) provide at least some aspect of this. There is both a light at the end of the tunnel, a reward, a break in what can often be a fairly miserable experience.

Using social media and online or other support groups is a way to get fairly immediate feedback, hopefully positive and rewarding when goals are accomplished. There is a current trend of letting Facebook know about workout and eating (although I think this revolves more around narcissism) but posting up a daily training or diet log to an online support community has the potential to provide some positive reward in the fact of delayed rewards. You did your workout and you get immediate attaboys. Is it enough to overcome a workout you might not have enjoyed? I don’t know but it doesn’t hurt.

This also provides accountability, knowing that you might get negative feedback for not following your plan can be just as powerful as receiving rewards. Many people seem to fear loss more than they desire rewards and knowing that someone may be disappointed can help to drive behavior.

This is another aspect of many commercial weight loss programs (with weeekly weigh-ins) or telling friends about your fat loss goals. It provides accountability (unless they exert a negative influence and try to derail you. But haters gonna hate, amirite?). Once again, religion itself or programs that use a higher being to provide accountability may also have a benefit in this regard (this was discussed elsewhere in this book, so drop it).

But going back to rewards, there is also an increasing amount of useful technology that can help to provide the currently lacking short-term rewards to what are fundamentally punishing behaviors. Many are attempting to gamify the process of exercise or eating, sites let people compete against each other, or give them achievements for attaining certain daily or weekly goals with apps on their phones.

You did a 45 minute workout, you get 45 points and an achievement. Yes this does provide only extrinsic rewards (another topic discussed elsewhere in the book) but this may be necessary in the early stages to keep people focused until the goal hopefully becomes self-sustaining and intrinsically self-rewarding.

But ultimately this approaches changes the goal of exercise or adhering to your diet to winning, achieving a gold star, or beating someone else instead of being related to some nebulous and far-away goal.

But irrespective of that, or the solution I’ll present in the next section of this book, the reality is that fat loss through diet and exercise will basically always involve some amount of restriction and conflict between short-term desires and long term goals. Which makes a nice transition into the next chapter, some more social psychology and biology that underlies this whole process.

And that’s that. I know the above seems incomplete in sections and I tried to add some necessary information so that it would make more sense. I’m not saying I have all the answers. I had the pleasure of discussing this with Dan John last year when he was in town. He saw the problem immediately with the reward/punishment dynamic being exactly reversed but neither he nor I had an immediately solutions to it. If you have thoughts, post ’em in the comments.

Facebook Comments